‘48

01

Willi Donnell Smith is born on February 29 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to Willie Lee Smith, an ironworker, and June Eileen Smith, an artist and homemaker.

‘63

01

Smith attends Jules E. Mastbaum Technical High School in Philadelphia and begins his first job as an illustrator for the dress shop Prudence and Strickler.

Related Articles

︎ Prudence Harvey Recollection

‘64

01

Smith takes a class in fashion illustration at the Philadelphia Museum College of Art.

Related Articles

︎ Alvin Bell Recollection

‘65

01

Designer Arnold Scaasi hires Smith as an apprentice.

02

Smith enrolls in the fashion design program at Parsons School of Design with two scholarships and takes liberal arts classes at New York University.

Related Articles

︎ Bonnie Brownfield Recollection

WilliWear to Streetwear

Jonathan Michael Square

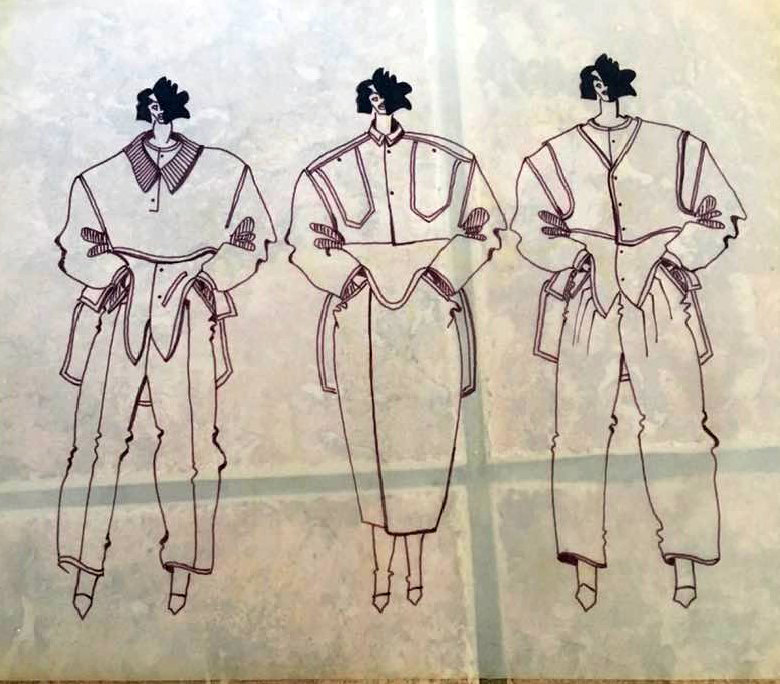

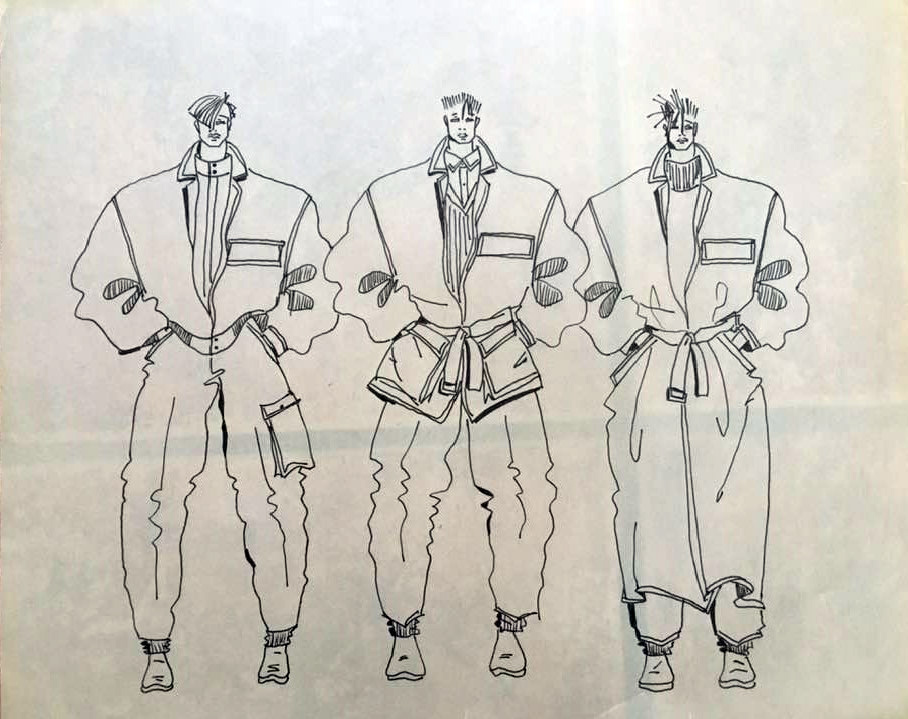

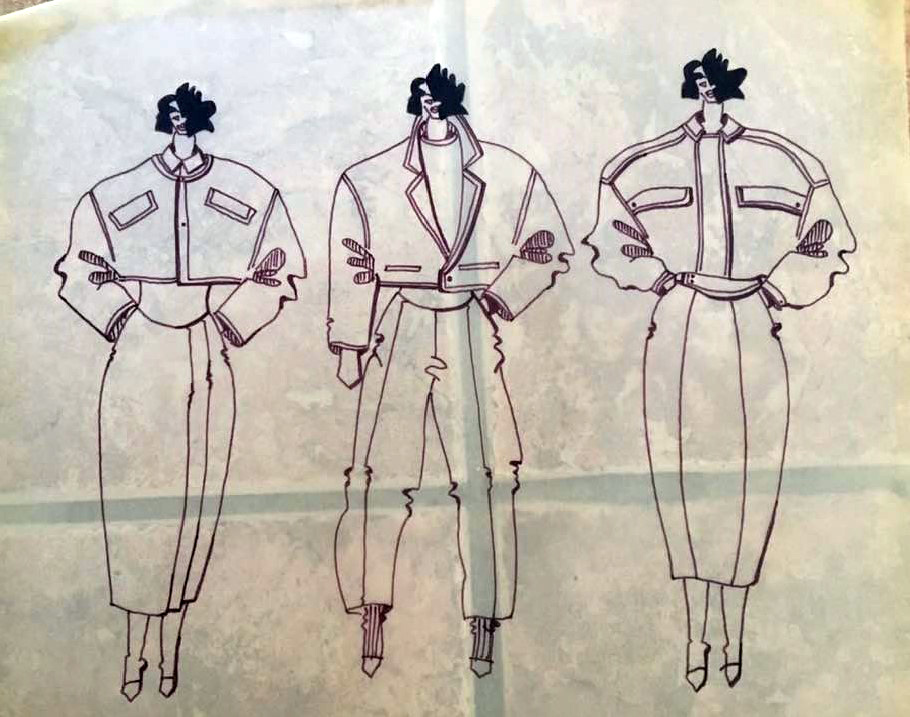

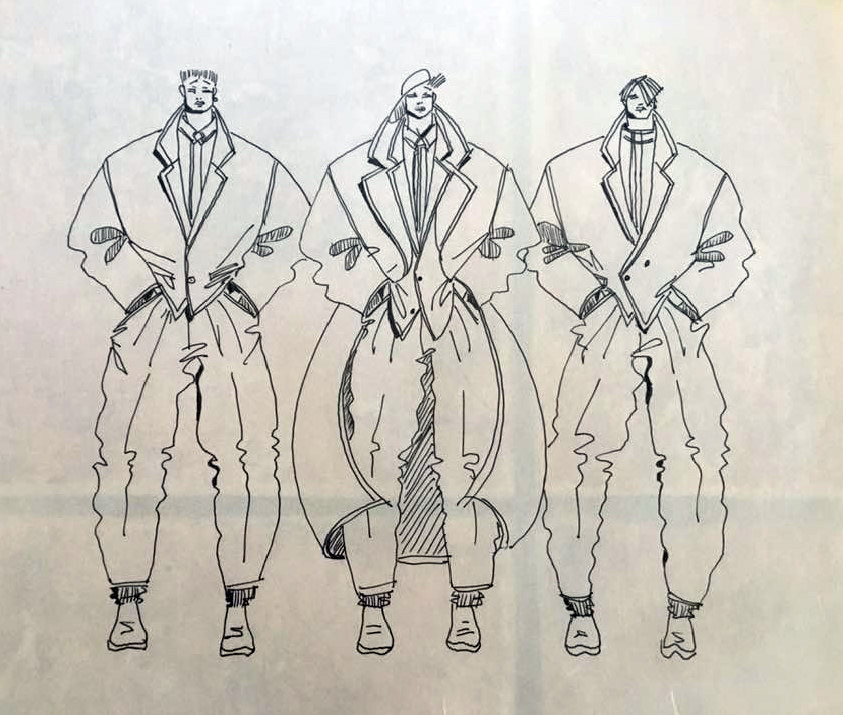

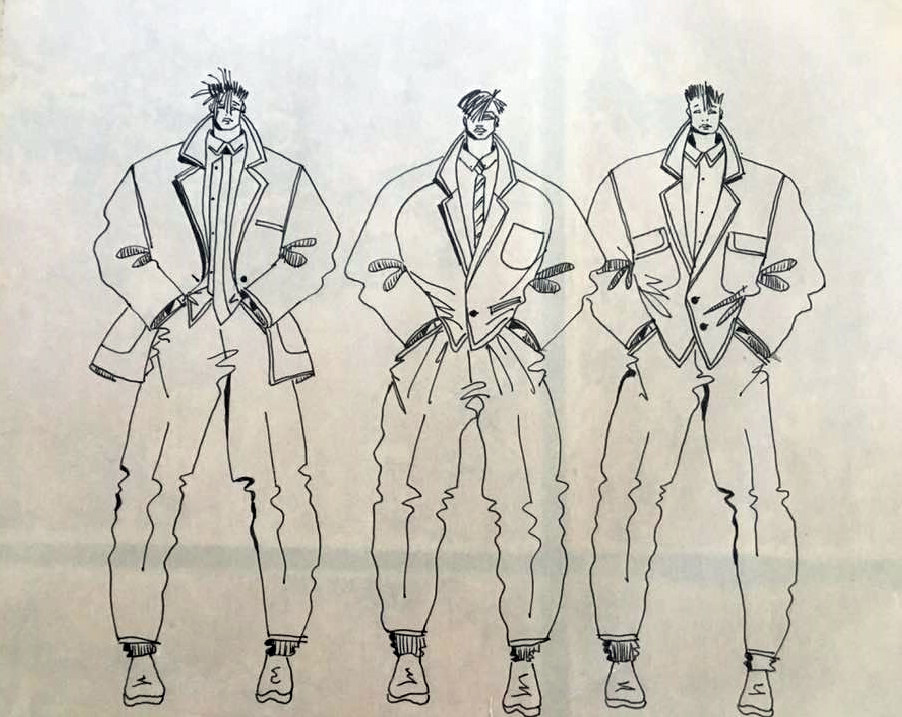

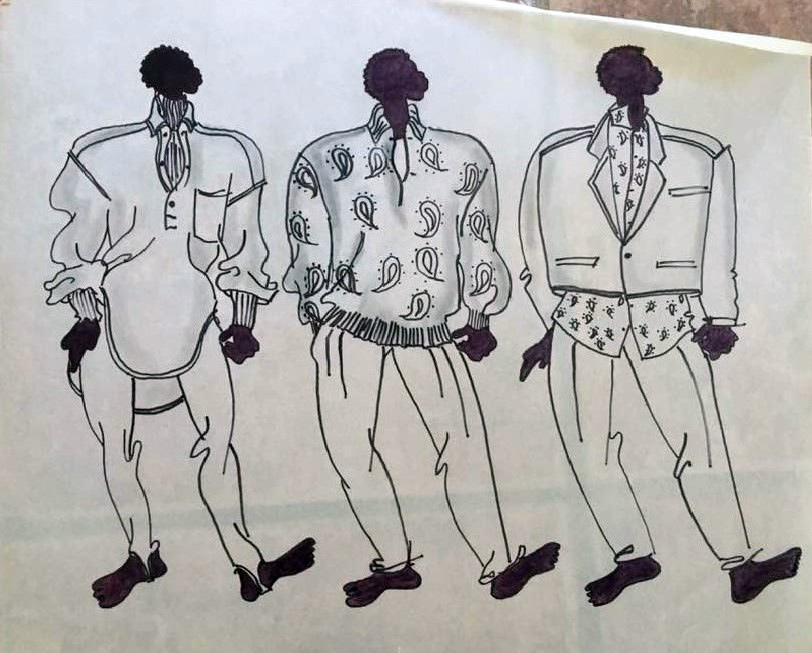

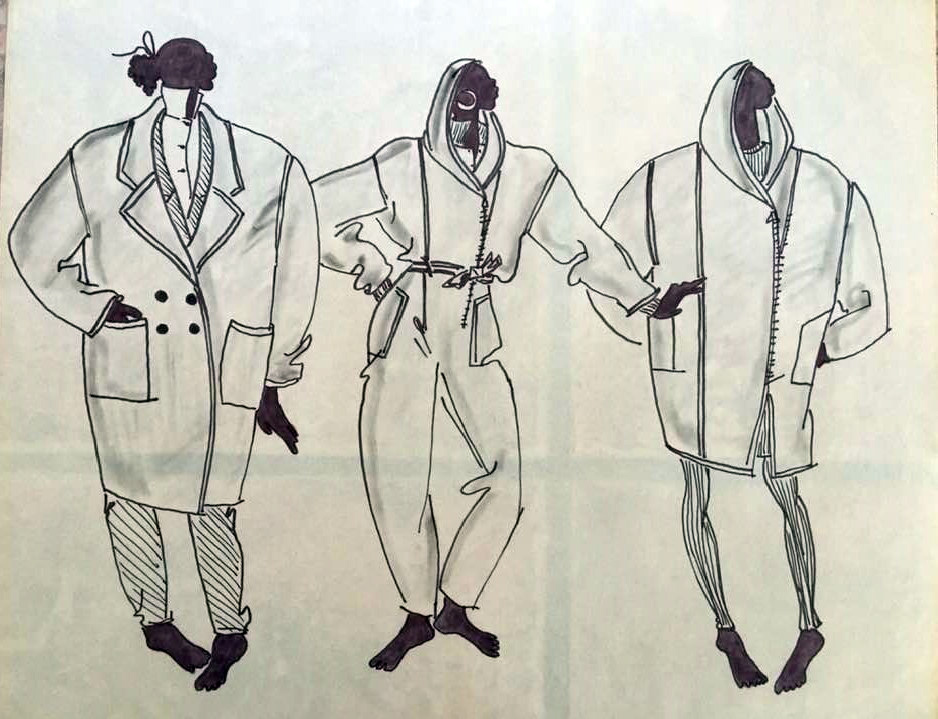

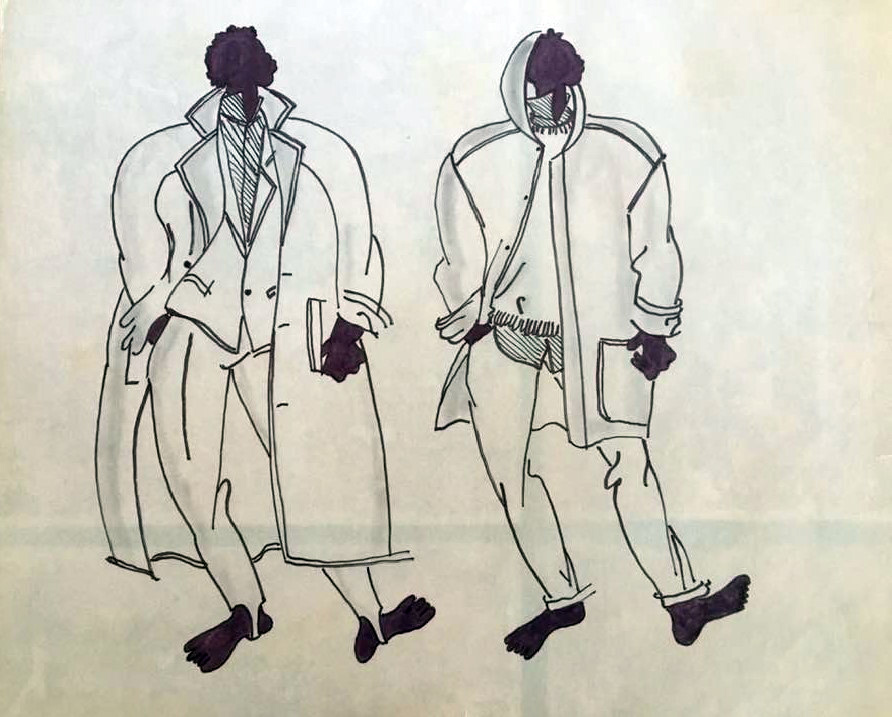

Willi Smith for Digits, Fall/Winter 1972 Collection, 1972

Willi Smith for Digits, Fall/Winter 1972 Collection, 1972

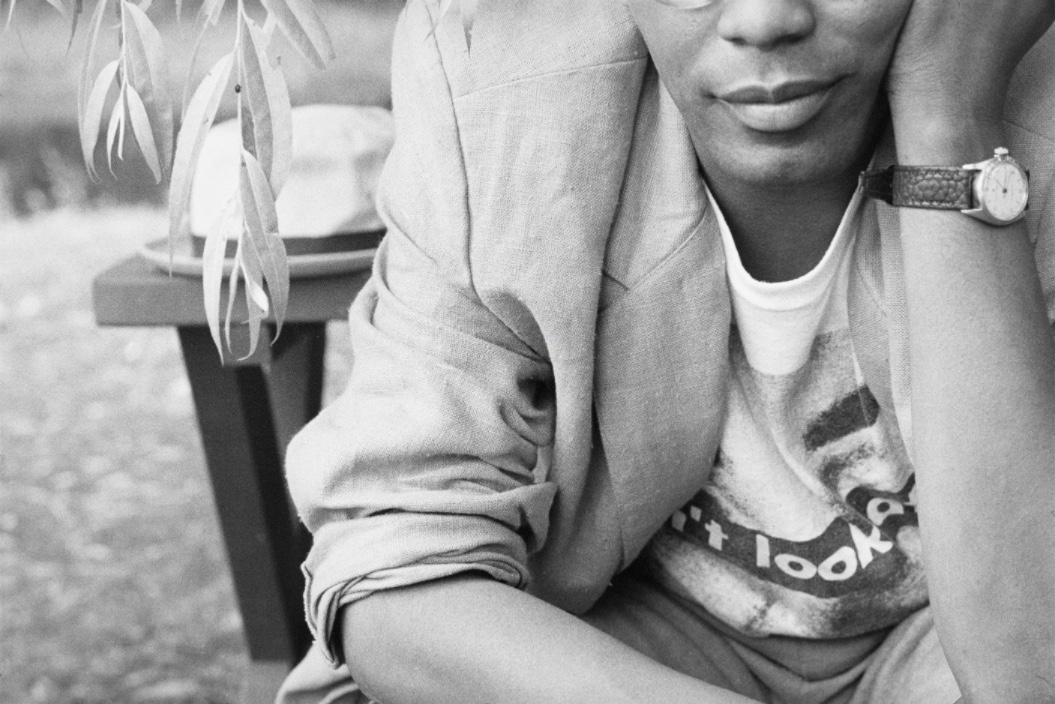

Willi Smith was an industry wunderkind when he spotted

Bethann Hardison on the corner of Broadway and 40th

Street. He admired her style and assumed that she was a

designer. “At that time, my style wasn’t very girly. It was

just really sporty,” said Hardison.1 One of Smith’s assistants arranged for Hardison to visit his showroom, and

Smith asked her to join his design team. Upon learning

that she was a showroom assistant at Ruth Manchester

Ltd., he asked her to model for him, initiating a friendship

that would last until his death.

This encounter between Smith and Hardison encapsulates Smith’s design process, which was fueled by the individuality and eclectic styles that saturated the streets of New York City in the seventies and eighties. “People who wear WilliWear clothes make fashion,” Smith told Morning Call in 1984. “I feel the person who wears my clothes is the person who wants to express himself . . . he doesn’t want to be intimidated by clothing.”2 In Hardison’s words, “You used to see WilliWear everywhere. It was a brand that you would see everyone wearing on the street. That’s why editors started referring to it as streetwear.”3

Under the umbrella of what was then sportswear, Smith’s reverb loop with the street set in motion streetwear, a moniker that has been interpreted and misinterpreted ever since. Streetwear, as molded by Smith, was an inclusive term that aimed to democratize the way fashion was consumed and experienced. But despite Smith’s popularization of streetwear, or “street couture” as he came to call it, his influence on the category has been overshadowed by brands emerging in the nineties that were closely associated with hip-hop culture, such as FUBU and Karl Kani.

This encounter between Smith and Hardison encapsulates Smith’s design process, which was fueled by the individuality and eclectic styles that saturated the streets of New York City in the seventies and eighties. “People who wear WilliWear clothes make fashion,” Smith told Morning Call in 1984. “I feel the person who wears my clothes is the person who wants to express himself . . . he doesn’t want to be intimidated by clothing.”2 In Hardison’s words, “You used to see WilliWear everywhere. It was a brand that you would see everyone wearing on the street. That’s why editors started referring to it as streetwear.”3

Under the umbrella of what was then sportswear, Smith’s reverb loop with the street set in motion streetwear, a moniker that has been interpreted and misinterpreted ever since. Streetwear, as molded by Smith, was an inclusive term that aimed to democratize the way fashion was consumed and experienced. But despite Smith’s popularization of streetwear, or “street couture” as he came to call it, his influence on the category has been overshadowed by brands emerging in the nineties that were closely associated with hip-hop culture, such as FUBU and Karl Kani.

Although it is difficult to pinpoint when the dialogue

between the street and the fashion industry began,

various periods of fashion history exhibit mainstream

fashion sampling from subcultures and the working

class. Notable examples include the robe de gaulle

chemise dress inspired by the simplicity of peasant

clothing and first seen worn by Marie Antoinette in Vigée

Le Brun’s 1783 portrait of the queen, and Balenciaga’s

integration of aprons in his haute couture designs

during the fifties. Fueled by globalization, technological

innovation, and wars, American streetwear’s predecessor sportswear emerged during the late nineteenth century/early twentieth century as casual dress,

like the shirtwaist and activewear that provided alternatives to the contemporary high style of the late Victorian

and Edwardian periods. The breakdown of traditional

sociocultural divisions resulting from the youthquake,

the women’s movement, and the civil rights era accelerated the industry’s embrace of a more casual style and,

in some cases, antifashion within these communities.

Eventually, boundary-breaking baby boomers adapted

activewear, workwear, and military uniforms into their

wardrobes. They took these elements of dress outside of

their original contexts, subverted them into quotidian

style, and ultimately changed their meaning.4

“Streetwear, as molded by Smith, was an inclusive term that aimed to democratize the way fashion was consumed and experienced.”

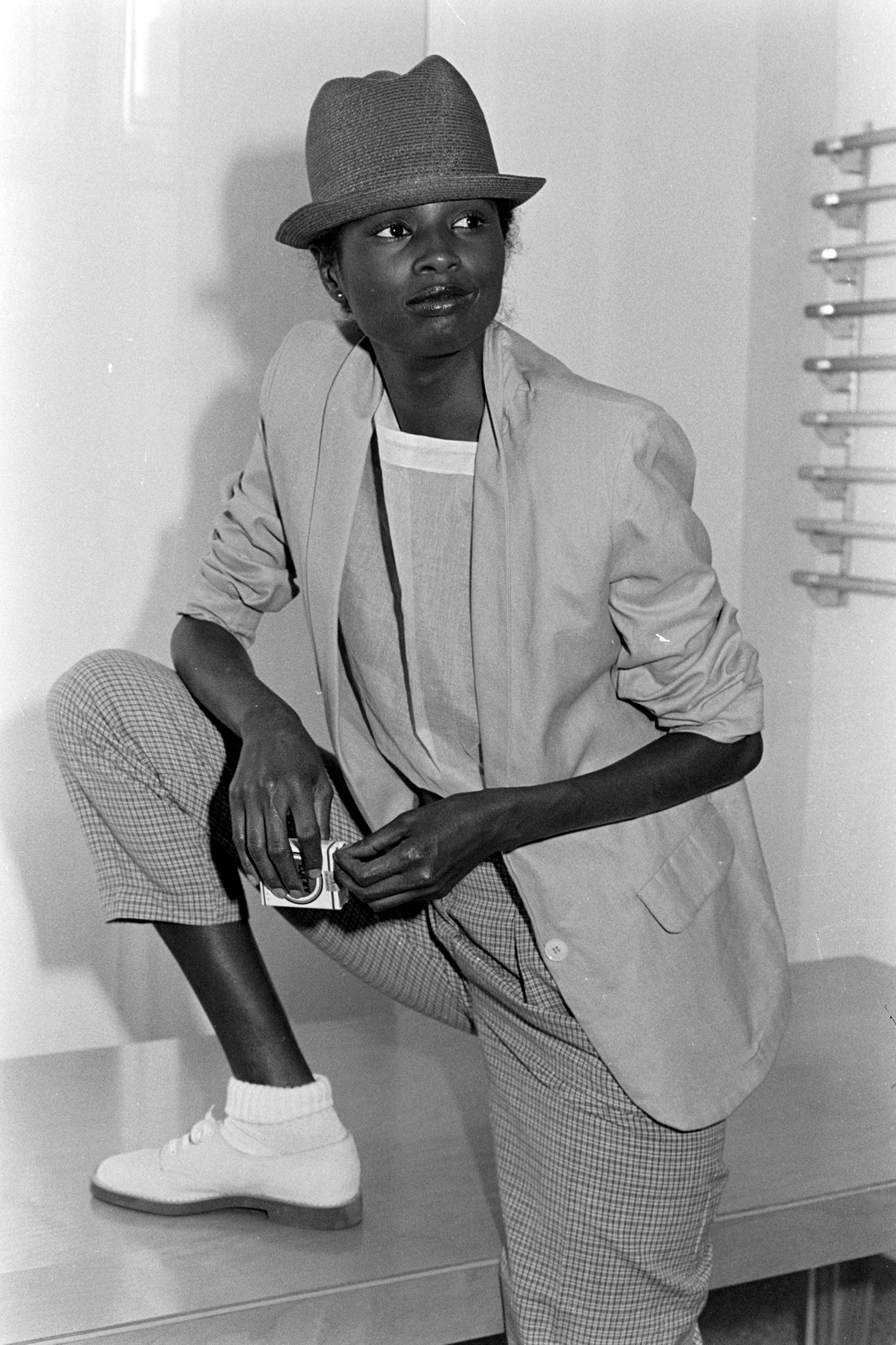

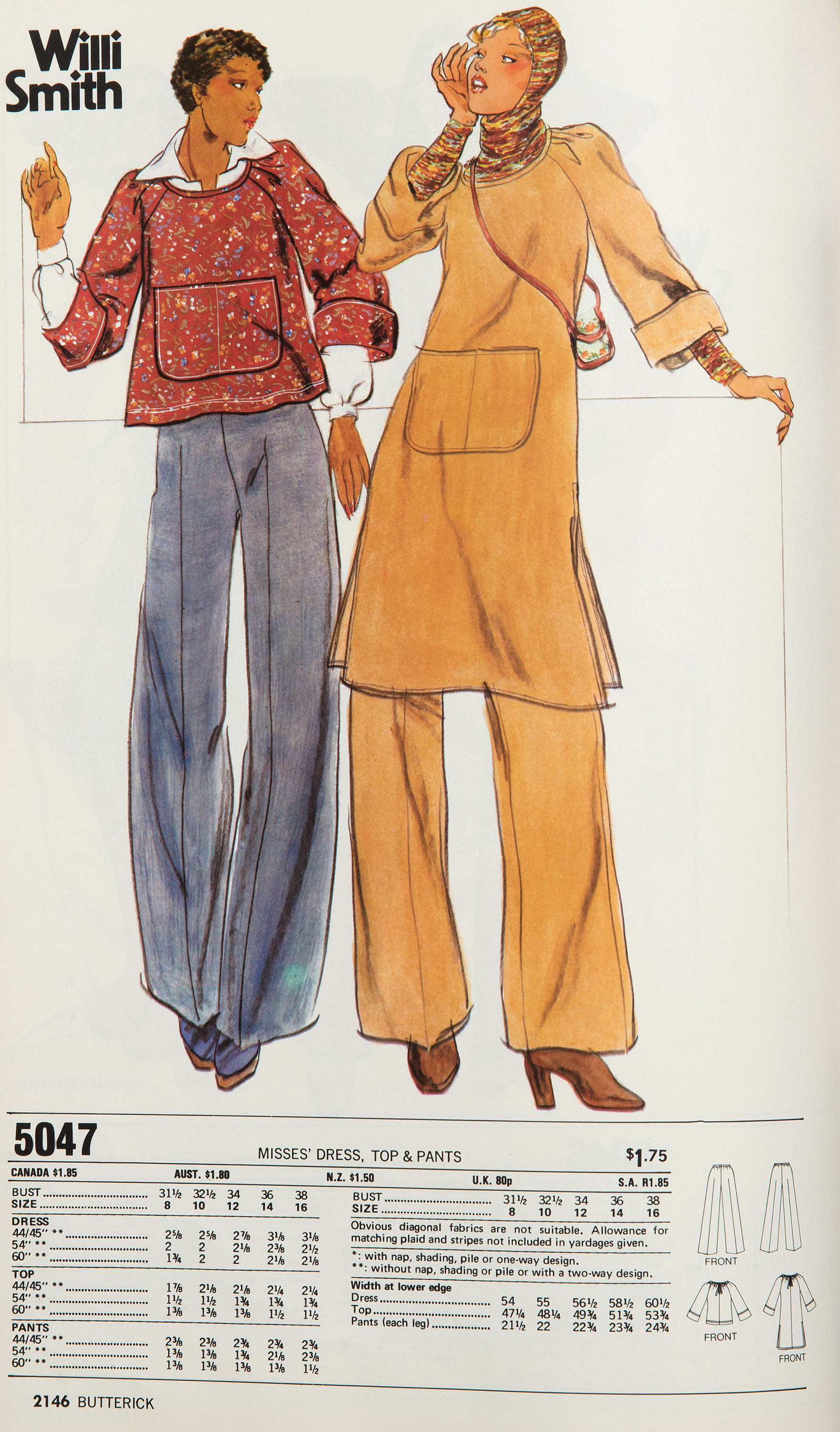

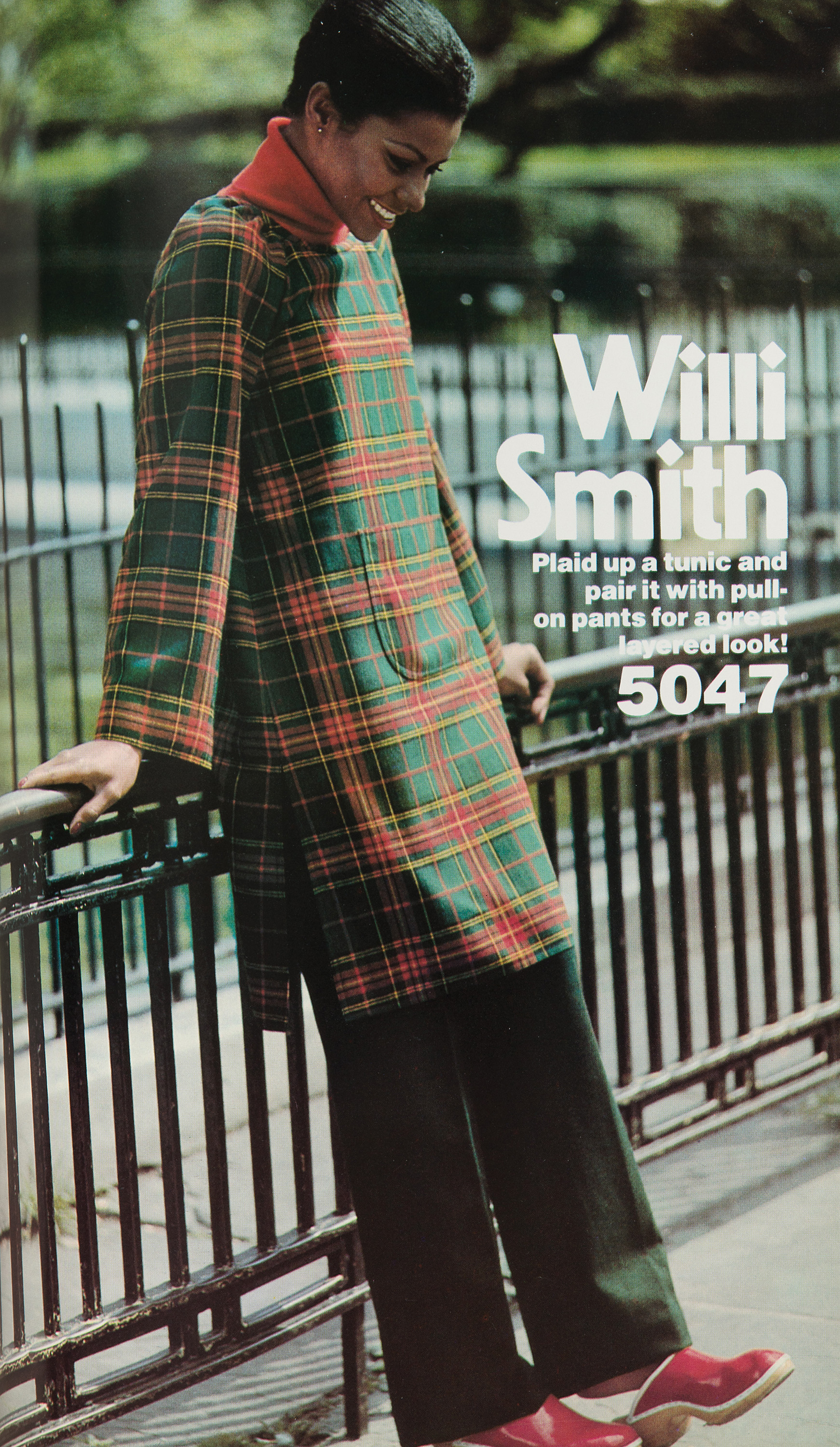

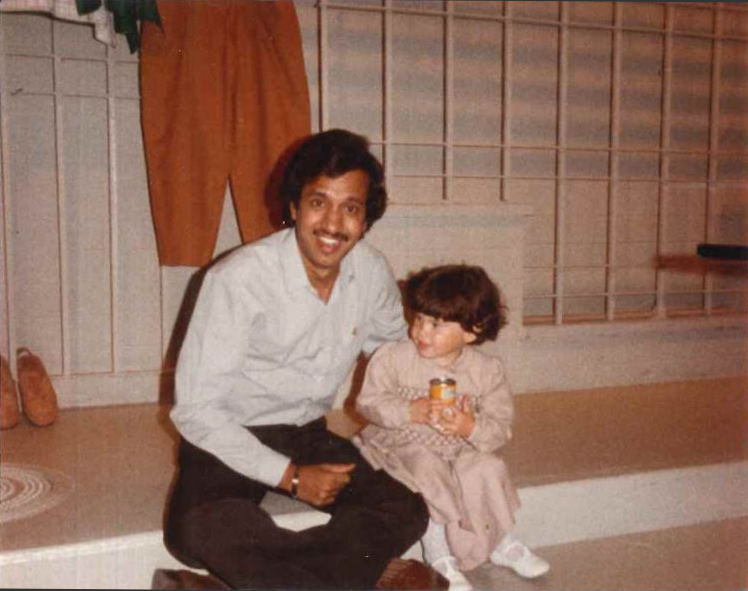

Like countercultural youths in the sixties, seventies, and eighties, Smith welcomed nonconformity, but was also a garmento who cut his teeth on Seventh Avenue. After leaving Parsons, he landed his first major job at age twenty designing for Glenora, then sportswear brand Digits, where he led the label until 1973. When he formed WilliWear in 1976, Smith was settling in as part of the fashion establishment alongside designers like Halston, Perry Ellis, Anne Klein, and Giorgio Armani.

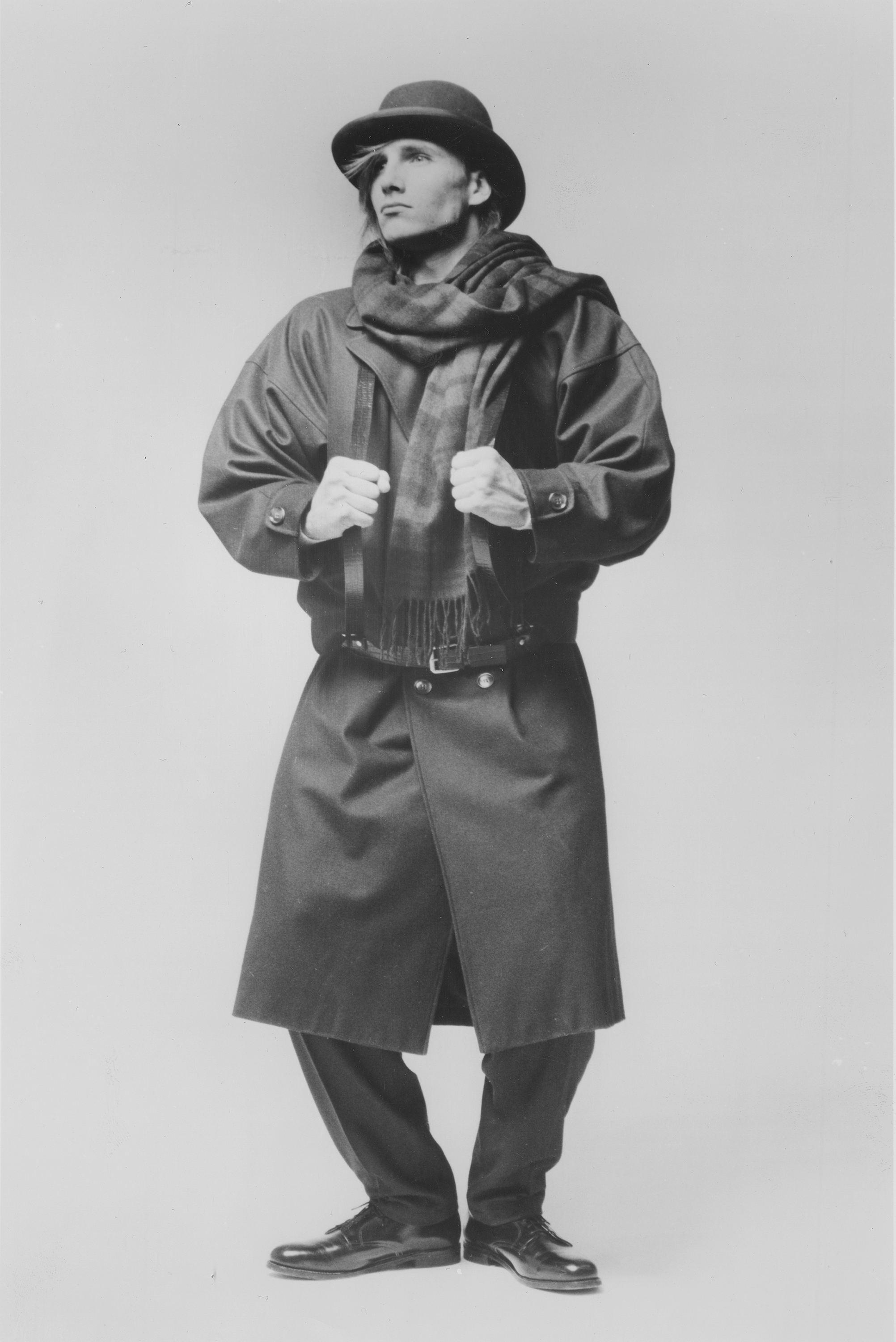

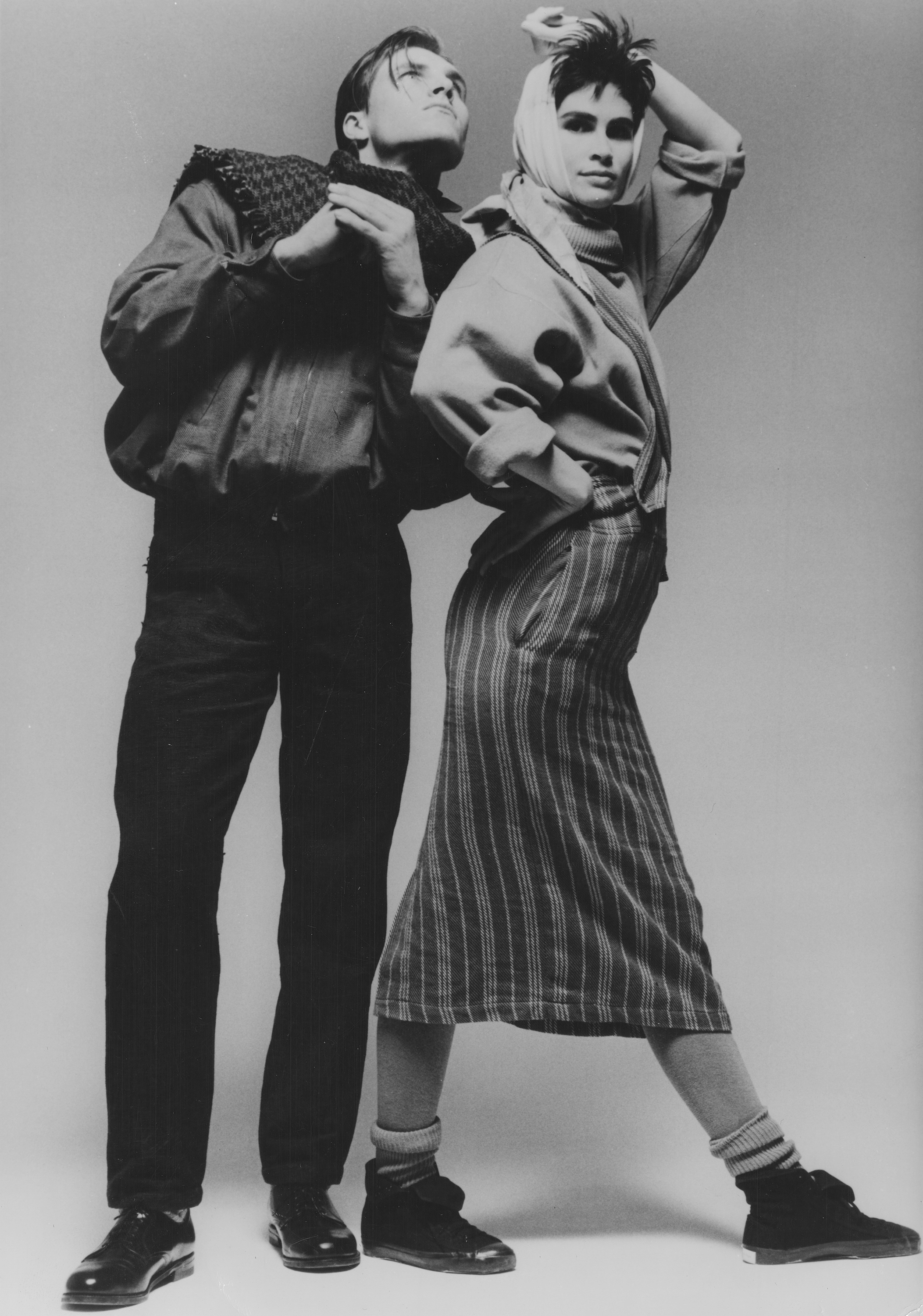

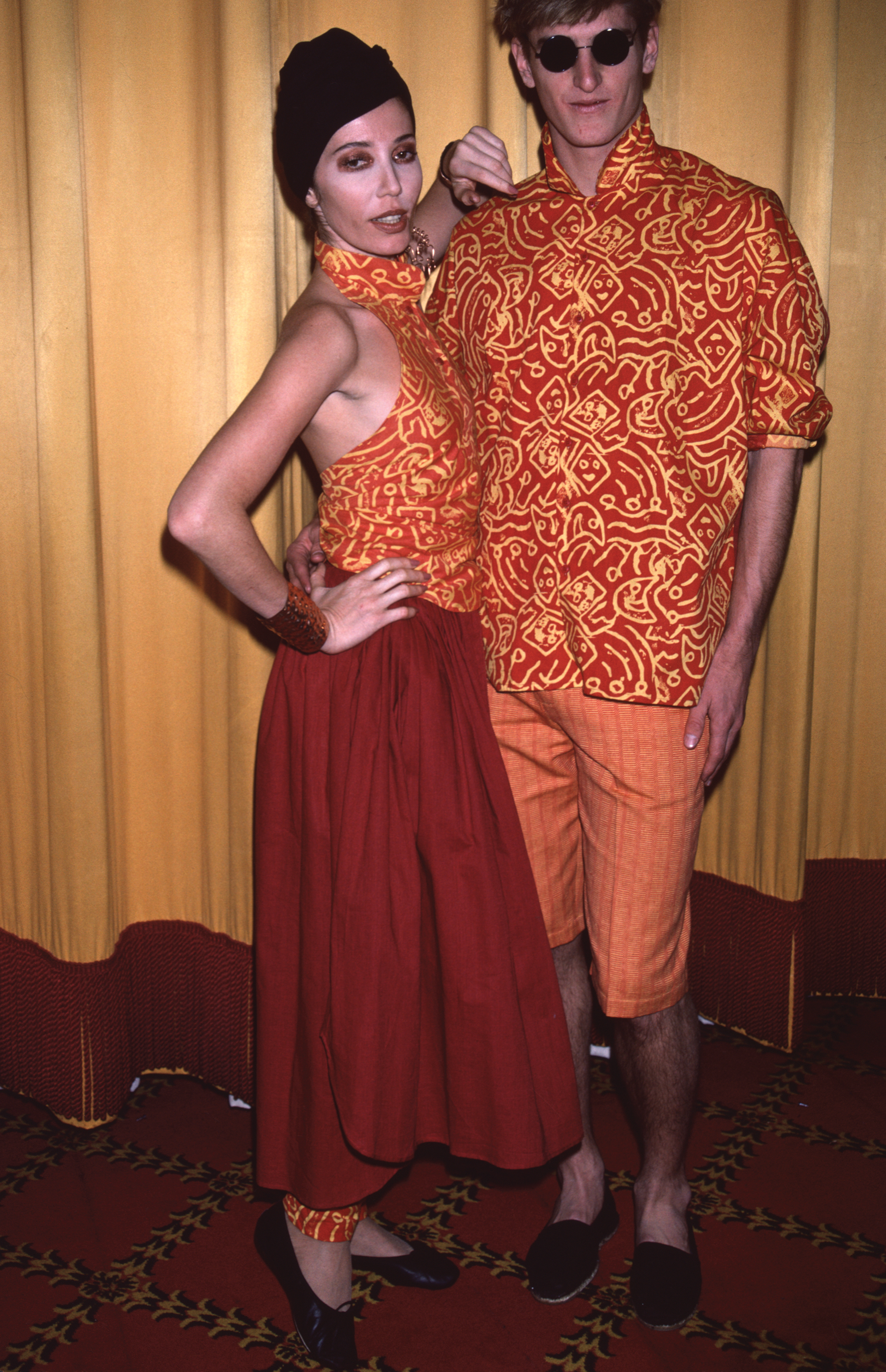

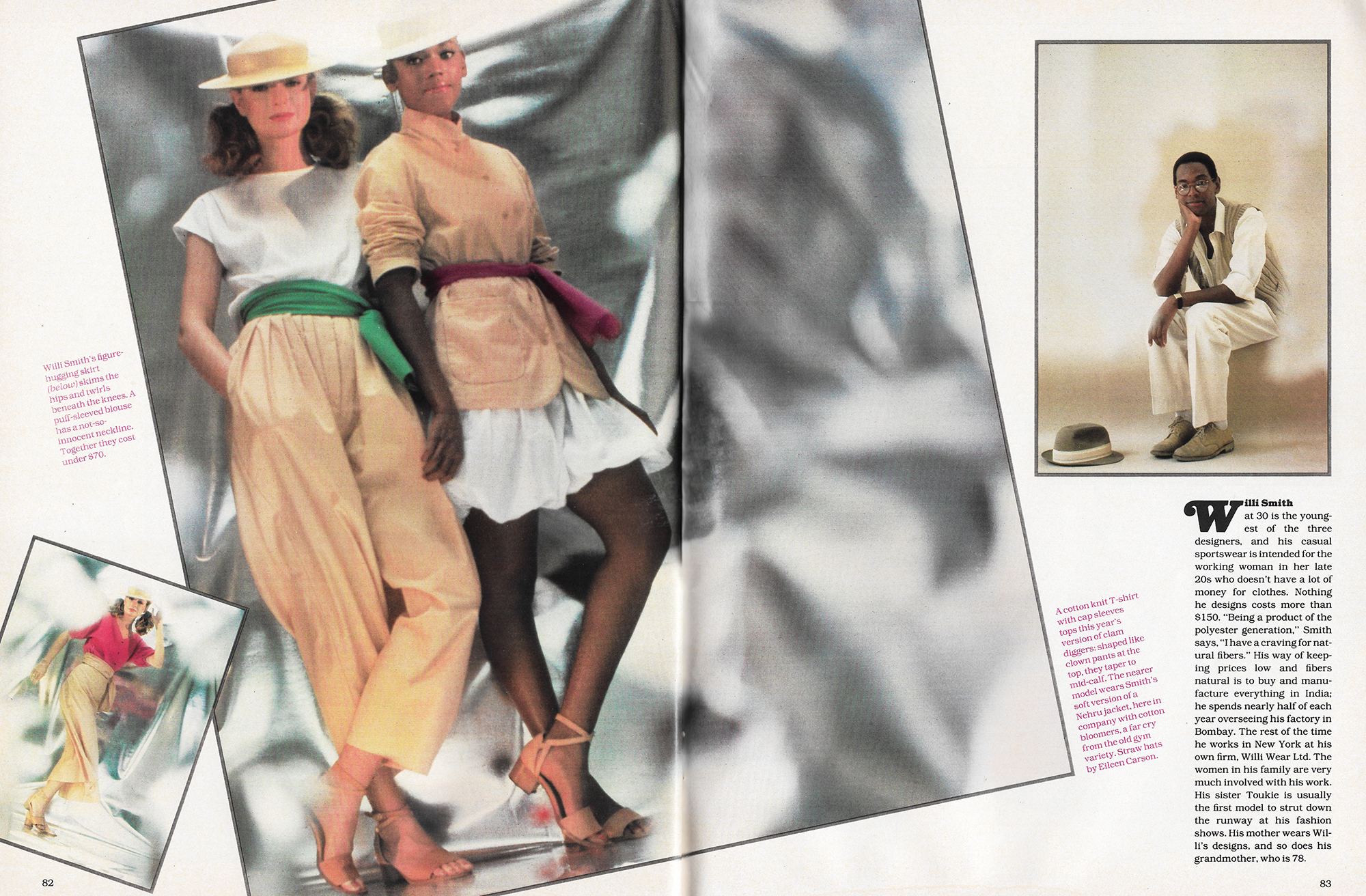

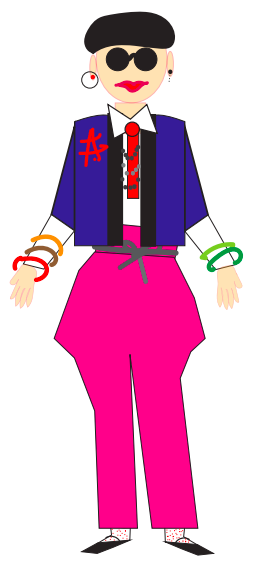

Smith’s take on streetwear was an eclectic yet irreverent twist on sportswear that elicited various identities from preppy silhouettes to billowing ensembles inspired by his passion for Indian and West African cultures. For example, his fall 1985 collection featured a plethora of themes, including colorful women’s suiting styled to transform the models into Spanish matadors juxtaposed against tapered plaid ensembles that emulated preppy country-club style. Smith focused on separates that allowed consumers to mix and match pieces from current and previous collections. He was a master of deconstructed suiting and had a penchant for gender-neutral silhouettes. He preferred plaids and stripes, bold prints and colors in natural, washable fibers that afforded the wearer both comfort and play.

Willi Smith for Digits, Fall/Winter 1972 Collection, 1972

Willi Smith for Digits, Fall/Winter 1972 Collection, 1972Along with Arthur McGee, Scott Barrie, Patrick Kelly, and

Stephen Burrows, Smith worked at a time that welcomed

the creative perspective of African American designers.

He laid the groundwork for other designers of color interested in redefining who could have access to fashionable

designs. He told Women’s Wear Daily in 1972, “I have it

through my head now to give women simple, packaged

clothes that adapt to a lifestyle, rich or poor. People really

only need a few clothes. My idea is that a woman could go

into a store, pick up a pack in blue, green, and black and

in it would be five pieces that all work. The only change a

woman should have to make in her wardrobe for spring

into winter is a coat.”5

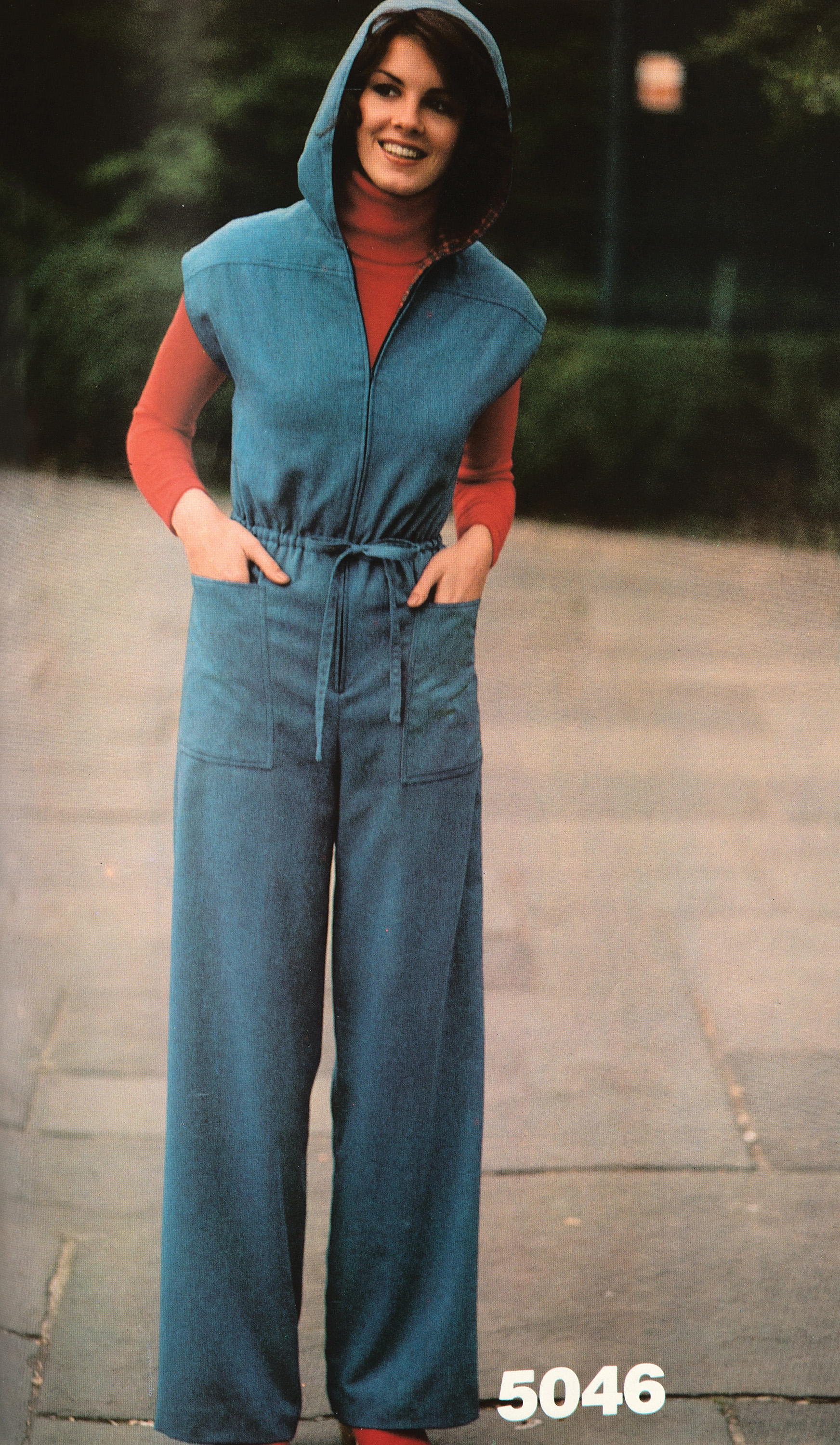

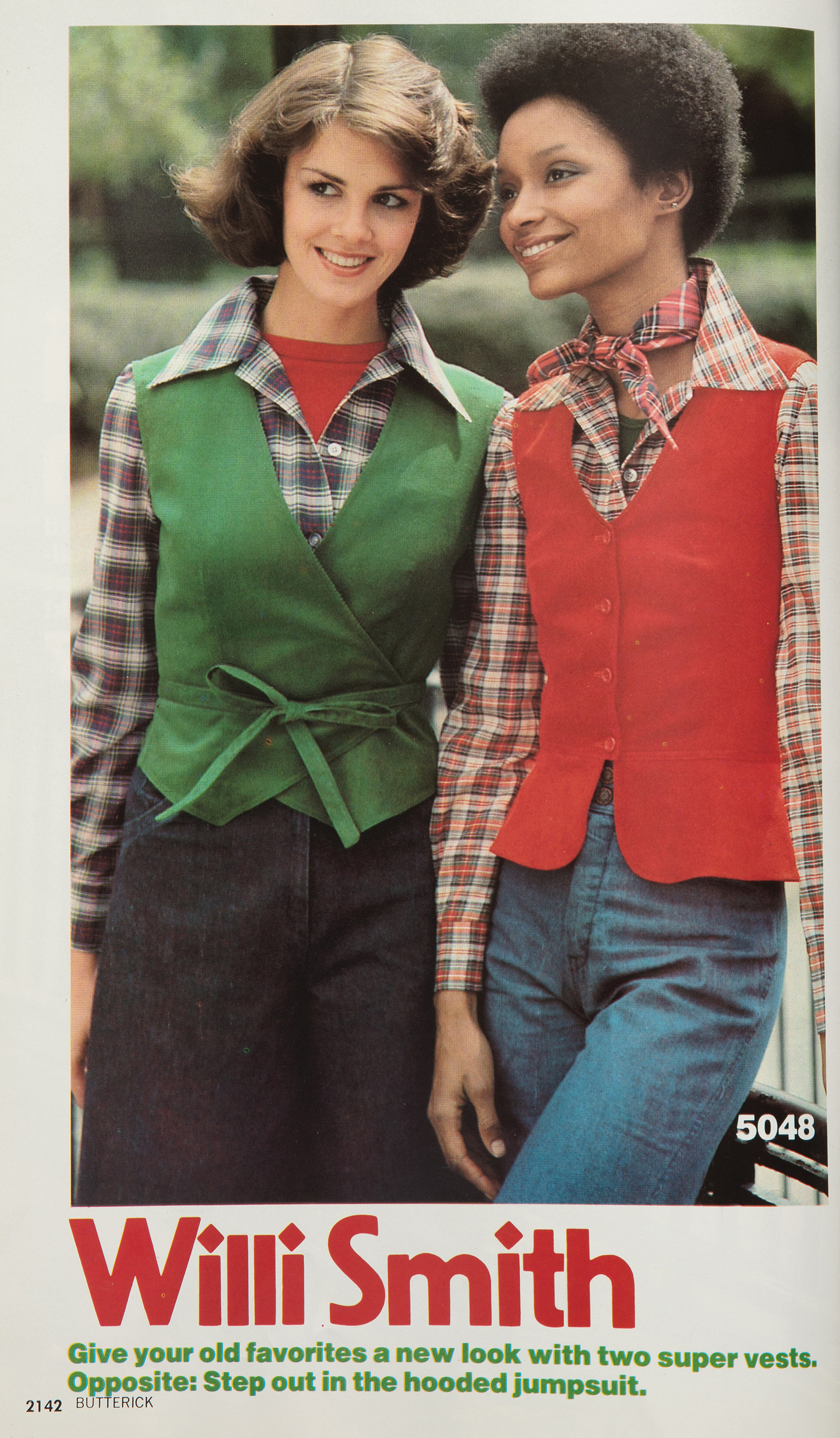

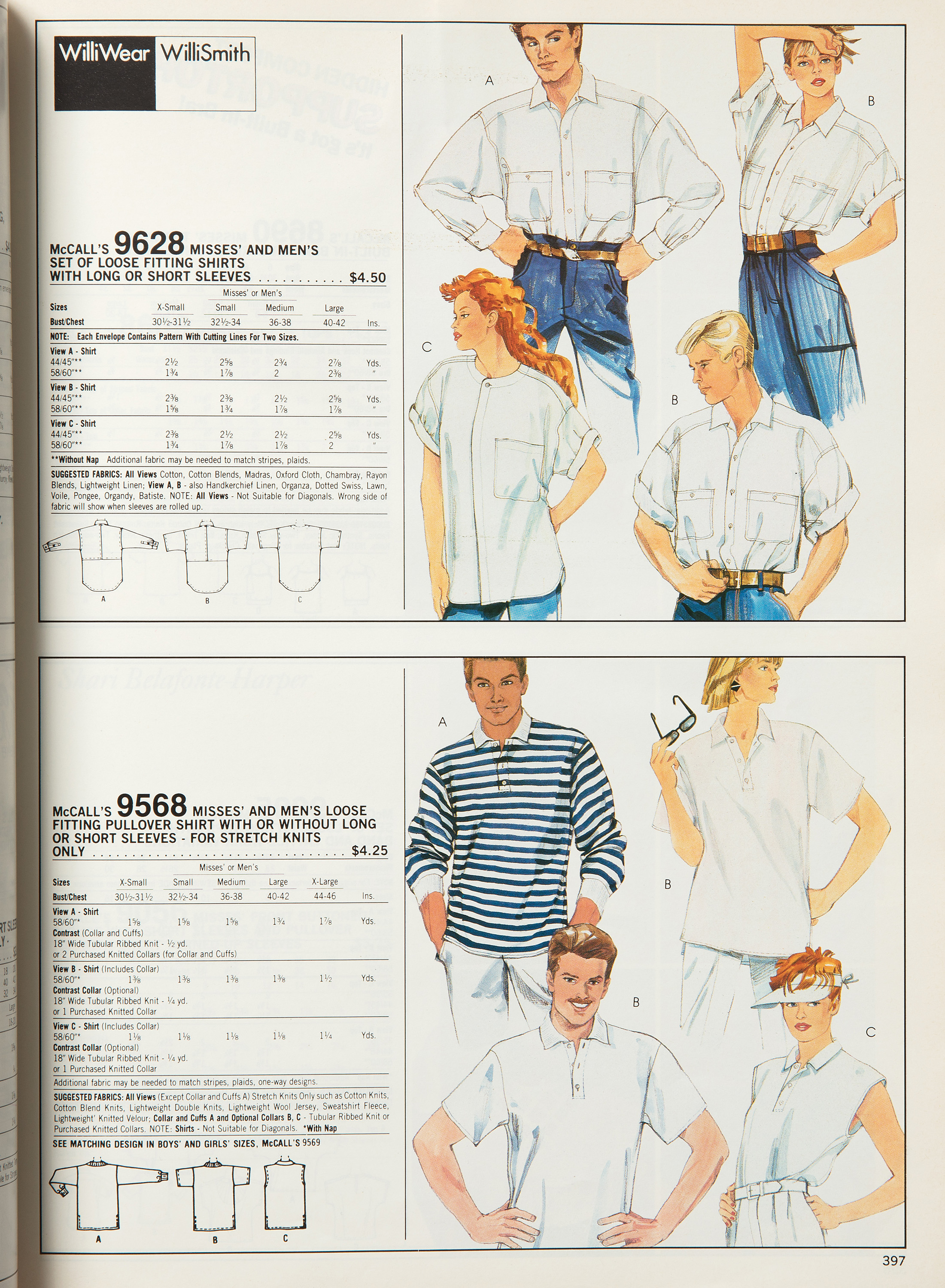

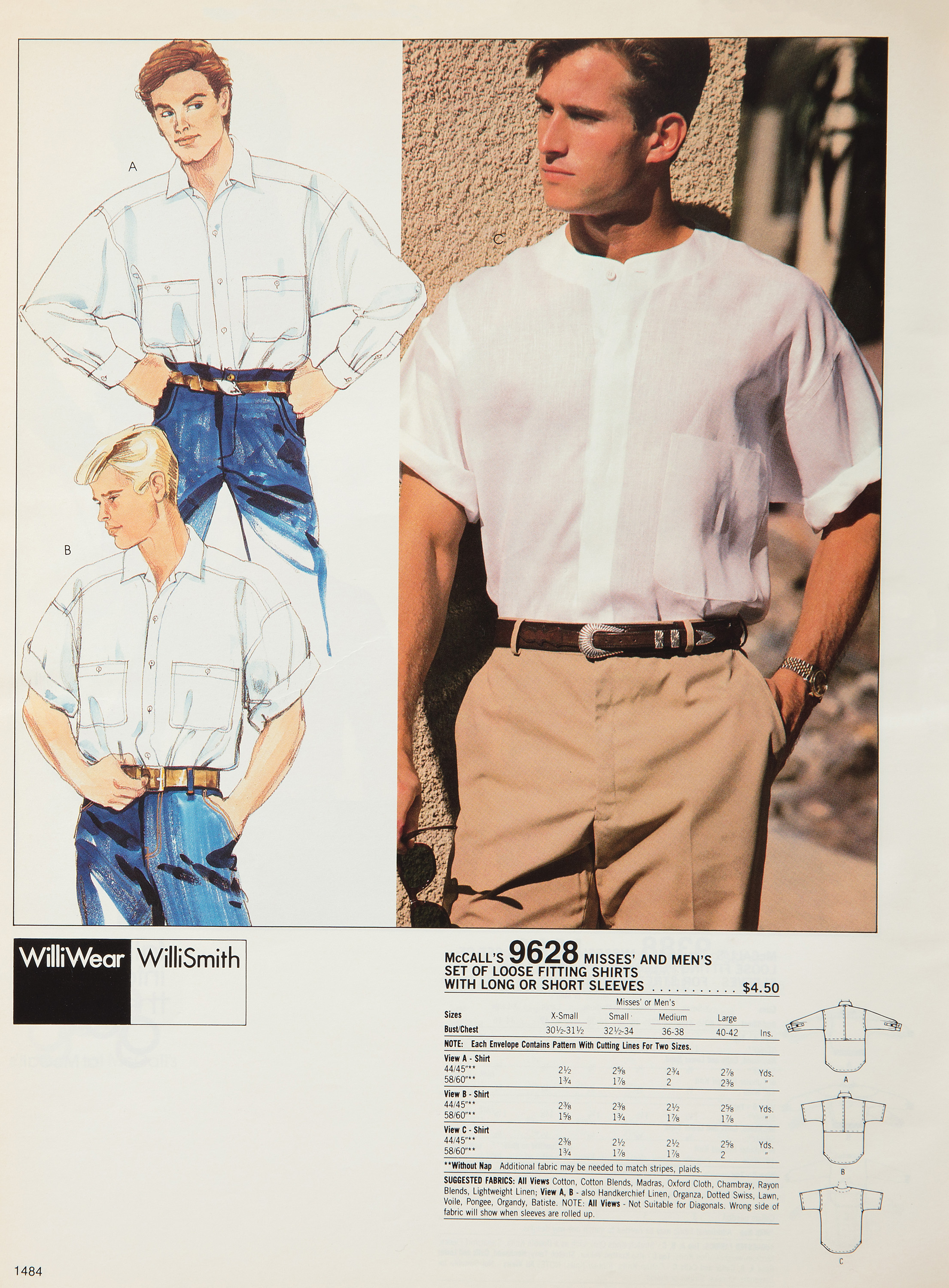

By designing pieces that favored a multitude of silhouettes, bodies, and gender identities, Smith was the first

designer to unite womenswear and menswear under the

same label.6 His gender-neutral designs extended to the

patterns he produced for Butterick and McCall’s, some

of which included images of men and women modeling

the same designs on the packaging and catalogue

editorial. He wanted his clothes to reach the widest

consumer base possible. Today, Smith’s fluid designs

would no doubt be championed and embraced by queer

and queer-allied consumers alike; they have influenced

labels that eschew gender norms, such as Eckhaus Latta,

Y/Project, Vaquera, and GmbH.

Parallel to and postdating the success of WilliWear, a

streetwear movement inspired by the early hip-hop

scene in New York City’s outer boroughs was accelerating. These Black-owned-and-designed labels like Cross

Colours, Karl Kani, and FUBU, which would become

popular shortly after Smith’s death, were formed outside

the fashion system. Smith, perhaps unwittingly, provided

a model for the success of these fashion companies.

Nineties streetwear designers Maurice Malone and April

Walker have both credited Smith for creating the first

bridge between the street and the runway,7 creating

fashion that was both inspired by and available to people

on the street.8

Today, luxury fashion and streetwear designers have joined forces. Designers like Virgil Abloh, Olivier Rousteing, and Kim Jones, who mix tailored suiting and couture-quality garments with T-shirts, sneakers, and hoodies, are leading Louis Vuitton, Balmain, and Dior. Brands like Supreme, A Bathing Ape (BAPE), and Kith have been elevated to luxury label status due, in part, to their overwhelming popularity among millennials and Gen Zers. Though these brands do not have the same affordable prices as WilliWear, the creators of these labels are driven to create fashion that reflects diverse audiences. Unlike early models of fashion, their aspirational luxury items are not inspired by or reserved solely for high-income consumers. Smith was the first to level the playing field.

Streetwear has come to describe a way of dressing among youth subcultures that is in contradistinction to—often in defiance of—high fashion. Although Smith was creating for and within traditional markets, he endeavored to refashion them for a wide and diverse audience through affordable collections and collaborations with music, art, and architecture. This model has been continuously reinterpreted and evolved by urban streetwear, high street, and luxury brands. Smith welcomed all to buy, wear, and enjoy his clothing, fueling a movement that is to this day helping us rethink accessibility and power in the fashion industry.

Jonathan Michael Square is a writer and professor of history at Harvard University, specializing in fashion and visual culture of the African diaspora. Square received a Ph.D. in history from New York University, a master’s from the University of Texas at Austin, and a bachelor’s from Cornell University.

Today, luxury fashion and streetwear designers have joined forces. Designers like Virgil Abloh, Olivier Rousteing, and Kim Jones, who mix tailored suiting and couture-quality garments with T-shirts, sneakers, and hoodies, are leading Louis Vuitton, Balmain, and Dior. Brands like Supreme, A Bathing Ape (BAPE), and Kith have been elevated to luxury label status due, in part, to their overwhelming popularity among millennials and Gen Zers. Though these brands do not have the same affordable prices as WilliWear, the creators of these labels are driven to create fashion that reflects diverse audiences. Unlike early models of fashion, their aspirational luxury items are not inspired by or reserved solely for high-income consumers. Smith was the first to level the playing field.

Streetwear has come to describe a way of dressing among youth subcultures that is in contradistinction to—often in defiance of—high fashion. Although Smith was creating for and within traditional markets, he endeavored to refashion them for a wide and diverse audience through affordable collections and collaborations with music, art, and architecture. This model has been continuously reinterpreted and evolved by urban streetwear, high street, and luxury brands. Smith welcomed all to buy, wear, and enjoy his clothing, fueling a movement that is to this day helping us rethink accessibility and power in the fashion industry.

Jonathan Michael Square is a writer and professor of history at Harvard University, specializing in fashion and visual culture of the African diaspora. Square received a Ph.D. in history from New York University, a master’s from the University of Texas at Austin, and a bachelor’s from Cornell University.

Willi Smith for Digits, Fall/Winter 1972 Collection, 1972

Willi Smith for Digits, Fall/Winter 1972 Collection, 1972- Bethann Hardison, interviewed by the author, 6. June 11, 2019.

-

Polly Rayner, “WilliWear Designer Creates ‘Basic Clothes with a Sense of Humor,’” Morning Call 7. (October 21, 1984).

-

Bethann Hardison, interviewed by the author, July 12, 2019.

-

Ted Polhemus, “Street Wear,” in Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion, ed. Valerie Steele (Farmington Hills: Gale, Cengage Learning, 2004): 225–29; Jennifer Craik, “Fashioning Sports Clothing as Lifestyle Couture,” in Uniforms Exposed: From Conformity to Transgression (Oxford: Berg, 2005): 161–74.

-

Ki Hackney, “Willi,” Women’s Wear Daily (January 1, 8. 1972), 4–5.

-

Rajat Singh, “Fashion Flashback: Willi Smith,”

February 17, 2017, Link.

-

“Designers of the Hottest 90s Brands Assemble at

Liberty Fairs & Agenda Shows, Las Vegas,” September

10, 2018, Link; Taylor

Lovaas, “Maurice Malone Breaks Down Hip Hop and

Fashion History from Mojeans to the Hip Hop Shop

+ Gives Advice to Young Designers,” Aug. 19, 2016,

Link.

- Elena Romero, Free Stylin’: How Hip Hop Changed the Fashion Industry (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Publishers, 2012), x.

To Be American

Dario Calmese

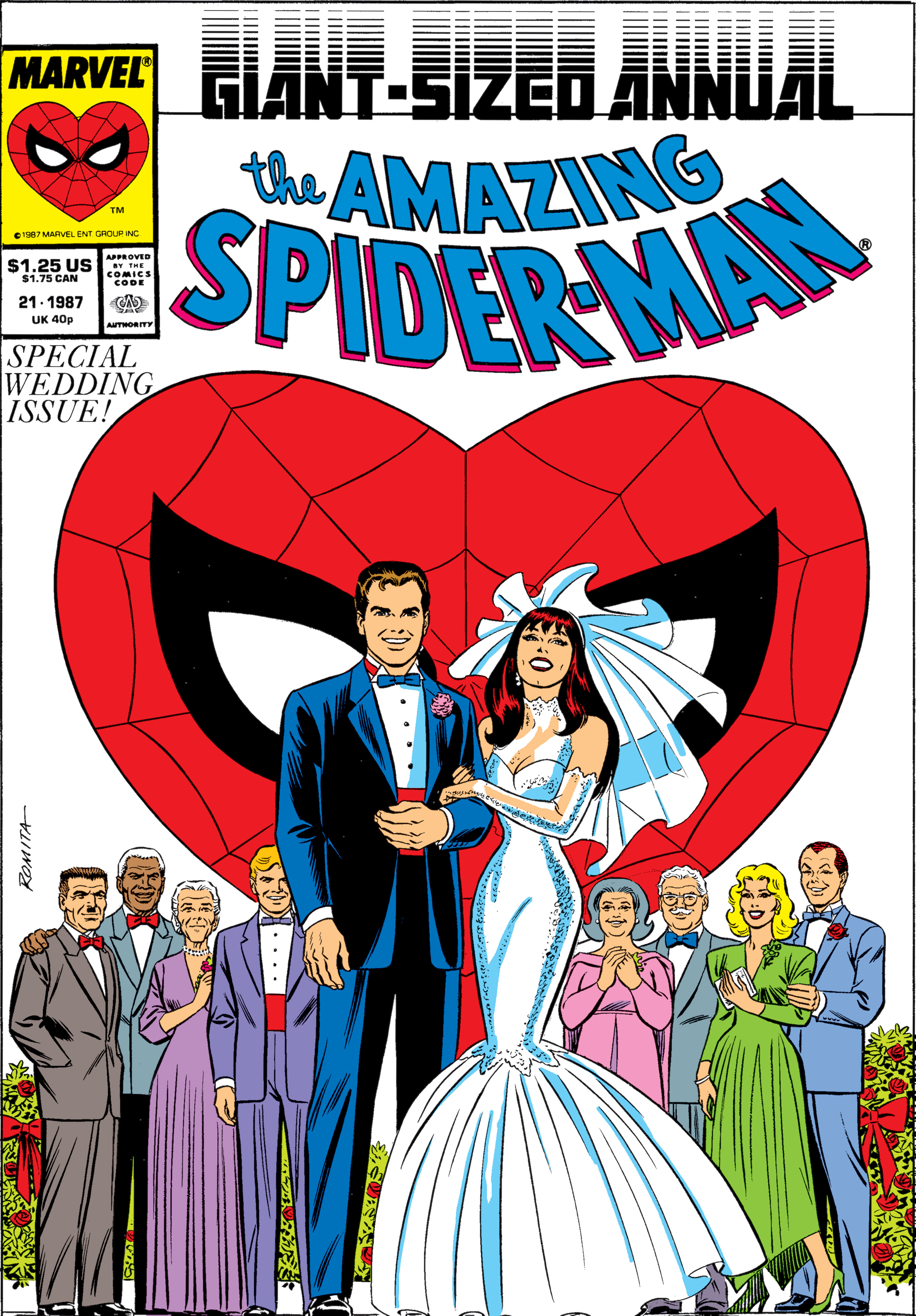

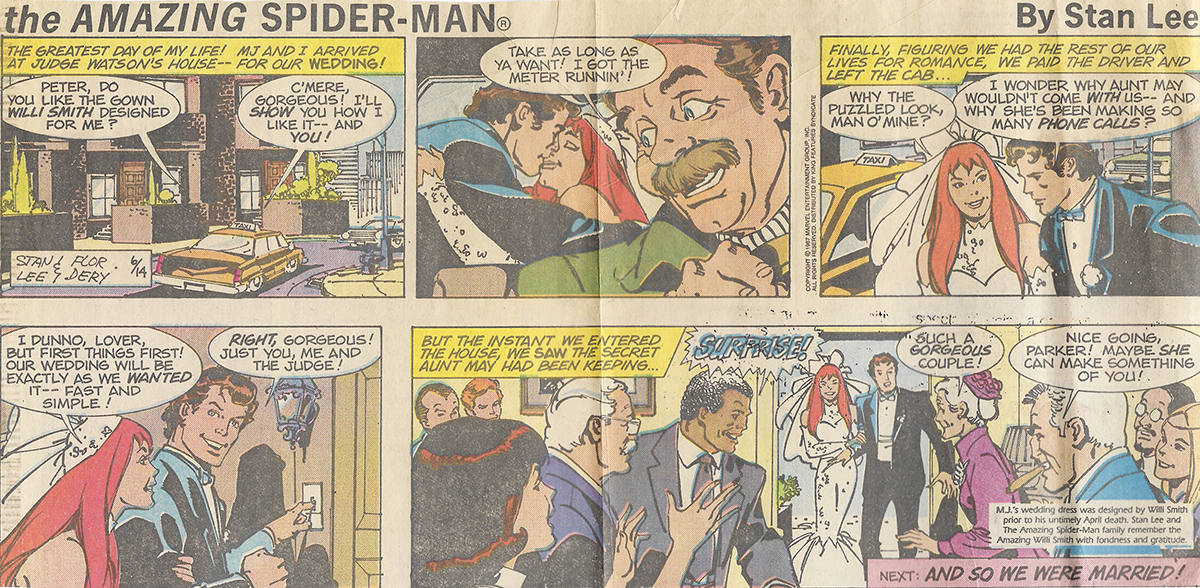

In contrast to the restrictive and fantastical designs of the European fashion houses during his time, Willi Smith’s WilliWear exuded and evolved the core tenets of American design: comfort, utility, and durability. His garments sat alongside Calvin Klein and Donna Karan in Vogue spreads, and his loose, easy separates were a favorite among Japanese women seeking to emulate the relatively liberated lives of their U.S. counterparts. His suiting draped the shoulders of artist Edwin Schlossberg, the bridegroom of America’s princess, Caroline Kennedy, on their wedding day1 (a sly nod to Ann Lowe, the “Negro dressmaker” who designed the wedding gown for her mother, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis). And his keen adoption of cross-disciplinary collaborations and new media amplified the mass appeal of WilliWear’s democratic vision. Smith established a new archetype for U.S. design values that led to an internationally successful brand. So why have Black Americans continually struggled to maintain a foothold in the world of fashion design?

“It’s so hard to make the Black girls look expensive,” recalls designer Charles Harbison, referring to a conversation during his days as an assistant at Michael Kors. The brand had requested a Black model to come in for a fitting but was stumped deciding on a look that would elevate her enough for the show. “That experience stuck with me,” he said. Class, race, and aspiration have always collided within fashion; a spectacle to induce desire. Coded in the language of Harbison’s quote is the question, “Who would desire to be Black?”

“It’s so hard to make the Black girls look expensive,” recalls designer Charles Harbison, referring to a conversation during his days as an assistant at Michael Kors. The brand had requested a Black model to come in for a fitting but was stumped deciding on a look that would elevate her enough for the show. “That experience stuck with me,” he said. Class, race, and aspiration have always collided within fashion; a spectacle to induce desire. Coded in the language of Harbison’s quote is the question, “Who would desire to be Black?”

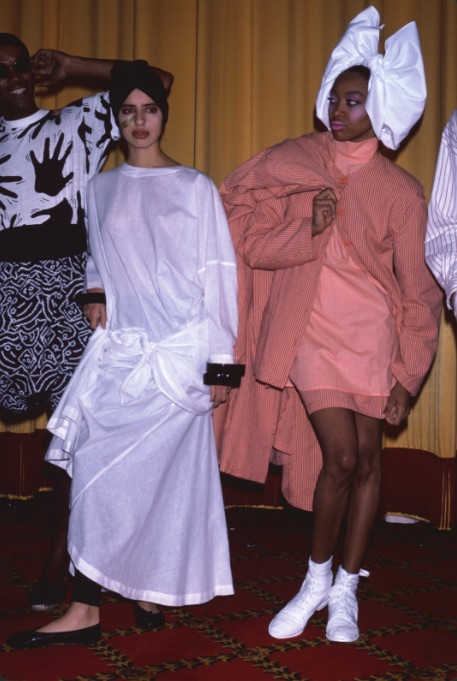

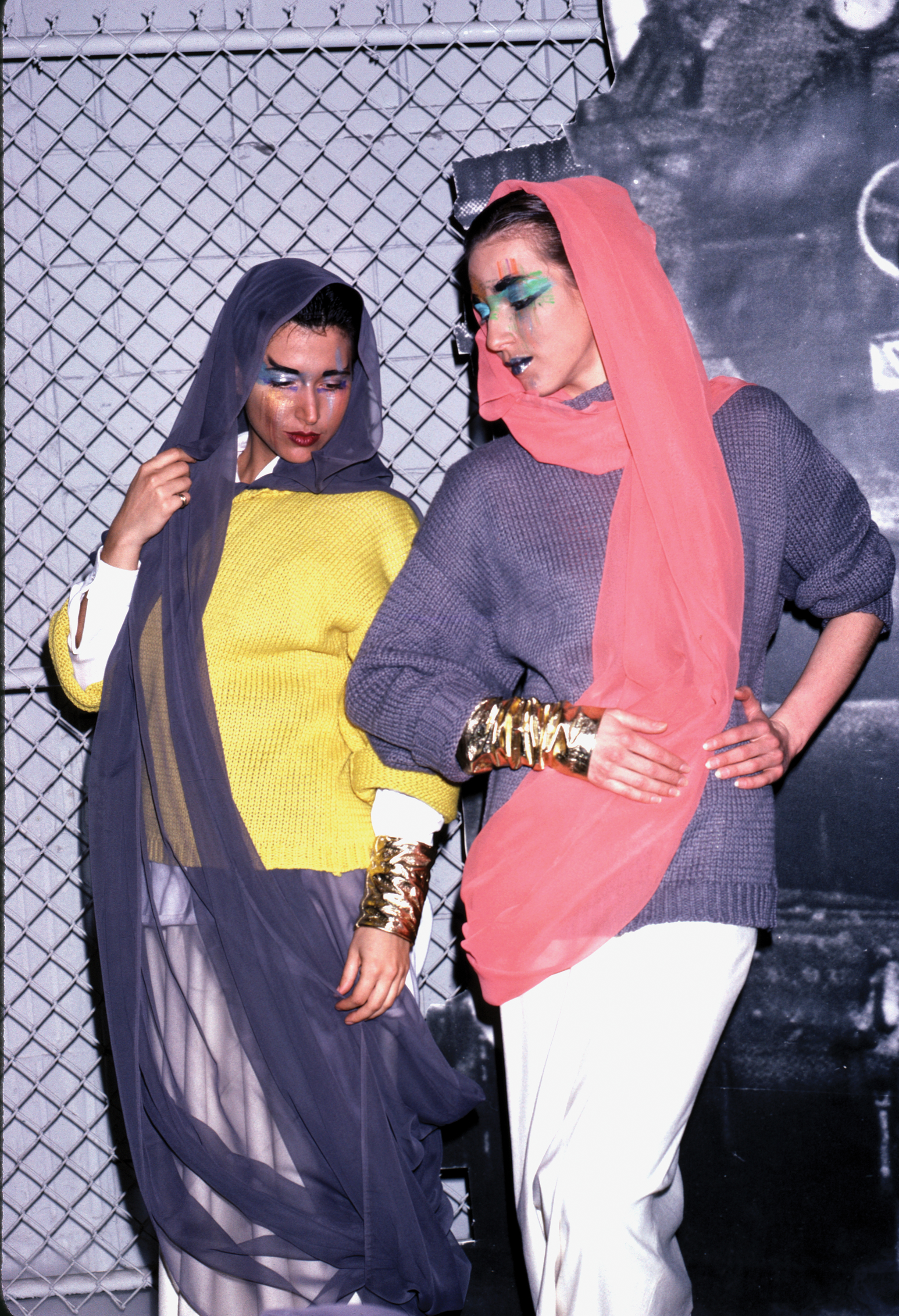

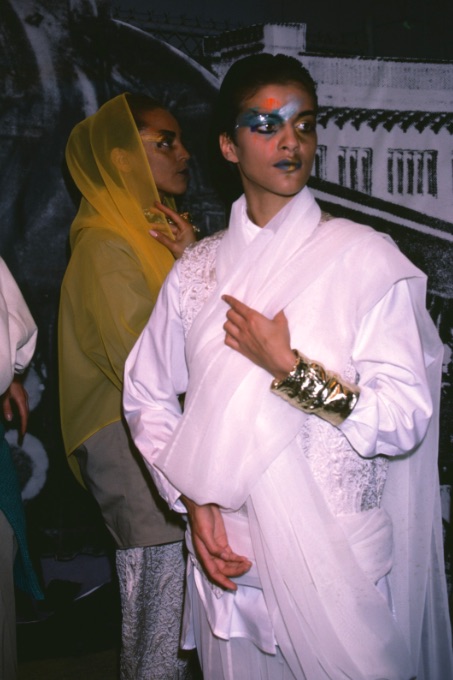

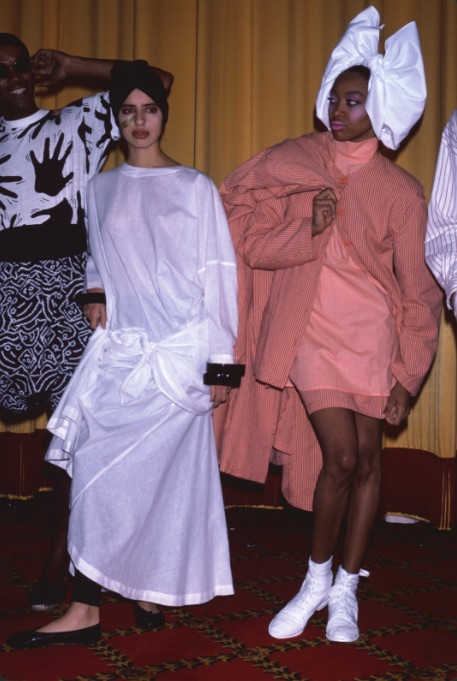

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Fall 1985 Presentation, Photographed by Peter Gould, 1985

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Fall 1985 Presentation, Photographed by Peter Gould, 1985

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring 1986 Presentation, Photographed by Peter Gould, 1985

In the introduction to his book of collected essays, Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin admits his internalized disdain for Negroes “because they failed to produce Rembrandt.”2 Reinterpreted in the world of U.S. fashion, one can ask, “Where is our Ralph Lauren?” However, the history of the fashion system and, more importantly, the history of the United States make that answer painstakingly clear. Since the late Middle Ages, fashion represented a concept of luxury, doused in opulent materials and stringent social protocol that was exclusive to aristocratic communities. “It was society ladies who put hats on other society ladies,” remarked fashion photographer Richard Avedon, referencing the style customs prominent in America and abroad at the funeral of his longtime collaborator, revered fashion editor Diana Vreeland.3 The term “society” is key to understanding that the fashion system was not constructed with Black people in mind. Avedon’s fateful meeting with Vreeland predated by two decades the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a piece of legislation meant to guarantee Black people full integration into U.S. society. Our Rembrandts have and do exist, but their creations have often been distributed through channels that dilute the source: Mary Todd Lincoln’s exquisite gowns, unattributed on lists of America’s most fashionable first ladies, were designed by Elizabeth Keckley, a former enslaved person; the wrap dress now associated with Diane Von Furstenberg began in Stephen Burrows’s studio. History is controlled by those in power.

Fashion is a hungry baby, and brands rely heavily on a motley crew of editors, writers, photographers, and investors to endorse brands. Today’s fashion shows cost upwards of $300,000, not including runway sample or staff salaries.4 Access to capital is the hobgoblin of the industry and can cripple designers, regardless of race; however, Black designers have often been held to a different standard, expected to convince investors that they have the taste level to dress society ladies as well as the acumen to run a sustainable business. Less than five percent of the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) members are Black.5

From Women’s Wear Daily’s sixties proclamation of the “Black explosion” to the miscategorization of many contemporary designers as “streetwear,” industry press coverage has been a double-edged sword, giving Black designers much-needed publicity while ghettoizing Black fashion production.6 “It’s upsetting, you know,” says Kerby Jean-Raymond, creative director of Pyer Moss in a 2016 interview with Elle magazine.7 “I’ve never seen Ralph Lauren, Rick Owens, or Raf Simons described as white designers.” In reference to the contemporary fashion press’s penchant for tossing Black design into the streetwear category, Jean-Raymond muses, “I just want to know what’s being called ‘street’—the clothes or me?” By continually categorizing designers based on race, the fashion press not only negates Black pluralism, but also flattens the dimensionality of their lives, experience, and creative output. Smith himself became weary of the monodimensional acknowledgment of designers of color. “You know, in the sixties and seventies there was this tremendous exposure given to designers based on their Blackness,” he states in a 1981 interview with Black Enterprise. “When the hype was over, people thought there were no more Black designers. In a way, it’s a blessing. Now we can get on with being what we are—designers.”8

Fashion is a hungry baby, and brands rely heavily on a motley crew of editors, writers, photographers, and investors to endorse brands. Today’s fashion shows cost upwards of $300,000, not including runway sample or staff salaries.4 Access to capital is the hobgoblin of the industry and can cripple designers, regardless of race; however, Black designers have often been held to a different standard, expected to convince investors that they have the taste level to dress society ladies as well as the acumen to run a sustainable business. Less than five percent of the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) members are Black.5

From Women’s Wear Daily’s sixties proclamation of the “Black explosion” to the miscategorization of many contemporary designers as “streetwear,” industry press coverage has been a double-edged sword, giving Black designers much-needed publicity while ghettoizing Black fashion production.6 “It’s upsetting, you know,” says Kerby Jean-Raymond, creative director of Pyer Moss in a 2016 interview with Elle magazine.7 “I’ve never seen Ralph Lauren, Rick Owens, or Raf Simons described as white designers.” In reference to the contemporary fashion press’s penchant for tossing Black design into the streetwear category, Jean-Raymond muses, “I just want to know what’s being called ‘street’—the clothes or me?” By continually categorizing designers based on race, the fashion press not only negates Black pluralism, but also flattens the dimensionality of their lives, experience, and creative output. Smith himself became weary of the monodimensional acknowledgment of designers of color. “You know, in the sixties and seventies there was this tremendous exposure given to designers based on their Blackness,” he states in a 1981 interview with Black Enterprise. “When the hype was over, people thought there were no more Black designers. In a way, it’s a blessing. Now we can get on with being what we are—designers.”8

At the time of Smith’s death, WilliWear generated more

than $25 million per year ($55 million in 2019 dollars)

and was carried in more than 1,100 global stores.9 Smith

subverted the spectacle Guy Debord described as the “unreal unity” masking “the class division on which the

real unity of the capitalist mode of production rests.”10 Via WilliWear, Smith upended the class divisions inherent

in the history of fashion by designing clothes not for the

queen but “for those who waved at her from the sidelines.”

His loose, liberated designs enhanced all body types, and

pieces were sold affordably. Beneath his genial manner,

Smith’s agenda was clear. “Who made the rule that everything in America that’s not expensive has to be horrible?”

he proclaimed to the Washington Post.11 Growing up watching the ways in which his mother and grandmother fashioned themselves, he understood that great style did not have to come at a great cost. The street, not bourgeois tastes, dictated trends. WilliWear flattened the fashion authority, undermining its aspirational reach and coating the white gaze with a Black aesthetic.

“When the hype was over, people thought there were no more Black designers. In a way, it’s a blessing. Now we can get on with being what we are—designers.”

In the nineties, after Smith’s passing, the garment

industry experienced a financial slump, which created a

space for voices that did not come through the traditional

fashion system. Brands like Karl Kani, Russell Simmons’s

Phat Farm, FUBU, and Cross Colours blossomed, epitomizing what was then called the “urban market.” Backed

by garmentos and the music industry, these brands

redefined streetwear and infused the industry with much

needed capital. This delineation between “fashion” and “streetwear” gave rise to brands like Sean Combs’s Sean

John and Baby Phat by Kimora Lee Simmons, which

sought to fuse the two worlds (Sean Combs went on to

win the CFDA Menswear Designer of the Year Award in

2004). Like Smith, they brought fashion to the streets, but while Smith designed for a broader clientele and

occasionally drew inspiration from Black culture, these

brands unapologetically centered Blackness in their

design aesthetic, branding, and target audience. However,

this alternative aesthetic, combined with a general lack of appreciation for the nuances of Blackness—within

fashion and America at large—would mark future Black

designers as “urban” despite their creative output.

The success of today’s cadre of Black designers continues to rely on subverting the fashion system. For his spring 2015 show, Jean-Raymond screened a fourteen-minute video showcasing police brutality before one model touched the runway with blood-splattered shoes. Virgil Abloh of Off-White and Louis Vuitton (LV) menswear used social media to usurp the fashion industry gatekeepers until the establishent itself came calling. Dapper Dan appropriated the codes of luxury by screen-printing LV and Gucci logos onto leather goods after the brands refused to allow him to sell their designs legitimately, a “hack” that predated LV ’s prêt-à porter line by thirteen years. He currently has his own Gucci atelier in Harlem. Even the demure Grace Wales Bonner engages the African diaspora through the lens of academia to quietly rewrite the codes of Black masculinity and reclaim the richness of Black culture via the American sportswear tradition. Donning loose, easy separates mixed with razor-sharp tailoring inspired by critical theory and Afro-Atlantic histories, her boyish and fey models not only redefined fashion’s ideal Black male (e.g., Tyson Beckford), but gave new voice to refinement Black peoples have always known and exhibited.

The history of fashion has been dominated by eurocentrism, hailing figures from Phillip the Good down to Alexander McQueen. Designed to advance privilege, the industry has repeatedly devalued the impact of Black peoples and Black culture. Smith’s efforts to connect art and industry, market through new media, and catalyze lifestyle and experience to create brand value laid the groundwork for the diverse voices breaking through industry protocol today. Contemporary Black designers are claiming their place in fashion history and the industry at large by writing a new narrative—not by those who control it, but by those who live it. Not for the queen, but for “those who wave at her from the sidelines.” This is America(n[a]).

The history of fashion has been dominated by eurocentrism, hailing figures from Phillip the Good down to Alexander McQueen. Designed to advance privilege, the industry has repeatedly devalued the impact of Black peoples and Black culture. Smith’s efforts to connect art and industry, market through new media, and catalyze lifestyle and experience to create brand value laid the groundwork for the diverse voices breaking through industry protocol today. Contemporary Black designers are claiming their place in fashion history and the industry at large by writing a new narrative—not by those who control it, but by those who live it. Not for the queen, but for “those who wave at her from the sidelines.” This is America(n[a]).

Dario Calmese is an artist, writer, director, and brand consultant currently based in New York City whose clients range from brands such as Pyer Moss and LaQuan Smith to publications including Vanity Fair and Numéro.

- Teresa M. Hanafin, “A Kennedy Is Wed, an Era Remembered,” Boston Globe (July 20, 1986).

- James Baldwin, opening essay in Notes of a Native Son (New York: Beacon Press, 1955)

- Michael Gross, The Secret, Sexy, Sometimes Sordid World of Fashions (New York: Atria Books, 2016).

- Fawnia Soo Hoo, “What a runway show really costs,” Vogue Business (February 5, 2019), Link.

- “CFDA Members,” CFDA, accessed June 1, 2019, Link.

- Sheila Banik, “Cutting on the Bias,” Black Enterprise 11, no. 12 (1981).

- Jessica Andrews, “Pyer Moss Designer Kerby Jean-Raymond Hates Being Labeled Streetwear,” Elle (February 12, 2016), Link.

- Banik, ibid.

- “Designer Willi Smith Dies,” Baltimore Afro-American (April 25, 1987).

- Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle (France: Buchet-Chastel, 1967).

- Gerri Hirshey, “Willi’s Way,” Washington Post Magazine, Style Section (1986).

Wedding Dress for the Black Fashion Museum

Elaine Nichols and Adrienne Jones

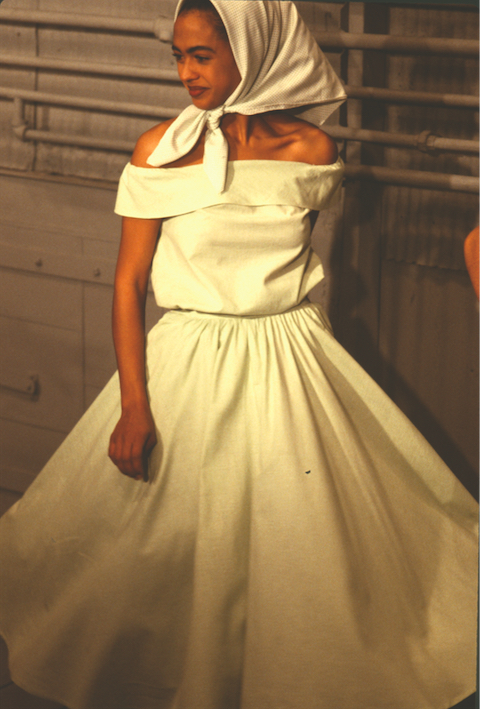

Willi Smith, Wedding Ensemble, ca. 1976–79

Willi Smith, Wedding Ensemble, ca. 1976–79

Throughout their lives, Willi Smith and Lois Alexander Lane worked in parallel to make fashion an inclusive and diverse industry. Smith advocated for the power of personal expression through his adaptable and affordable designs, while Alexander Lane built foundation for African American achievement in fashion. Various examples of Smith’s designs, including an unusual bridal ensemble, are preserved in Alexander Lane’s Black Fashion Museum (BFM) collection, which was donated to the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture in 2007 by Alexander Lane and her daughter Joyce Bailey.

Beginning in the late sixties, Alexander Lane created community-driven institutions that educated and promoted young, aspiring fashion designers. In 1966, she founded the Harlem Institute of Fashion (HIF) to teach African American students Black history, ways to improve their reading, writing, and math skills, and how to navigate the fashion industry.1 In 1979, Alexander Lane established the BFM to provide visual proof that African Americans contributed to the world of fashion from the period of slavery to the modern era. Her work as a historian, organizer, and activist nurtured and preserved Black fashion history. The BFM collection serves as an invaluable resource for understanding the works of Ann Lowe, Geoffrey Holder, Patrick Kelly, Stephen Burrows, and Willi Smith, among many others.2

In 1981, Alexander Lane mounted a seminal exhibition at the BFM entitled Bridal Gowns by Black Designers. Among the numerous traditional gowns was Willi Smith’s rajah-style cotton satin jacket and beige-colored velveteen jodhpurs. It captured the progressive spirit of the time, boldly bent the lines of gender, identity, and cultural dress, and challenged standards for one of society’s most sacred global ceremonies.3

Beginning in the late sixties, Alexander Lane created community-driven institutions that educated and promoted young, aspiring fashion designers. In 1966, she founded the Harlem Institute of Fashion (HIF) to teach African American students Black history, ways to improve their reading, writing, and math skills, and how to navigate the fashion industry.1 In 1979, Alexander Lane established the BFM to provide visual proof that African Americans contributed to the world of fashion from the period of slavery to the modern era. Her work as a historian, organizer, and activist nurtured and preserved Black fashion history. The BFM collection serves as an invaluable resource for understanding the works of Ann Lowe, Geoffrey Holder, Patrick Kelly, Stephen Burrows, and Willi Smith, among many others.2

In 1981, Alexander Lane mounted a seminal exhibition at the BFM entitled Bridal Gowns by Black Designers. Among the numerous traditional gowns was Willi Smith’s rajah-style cotton satin jacket and beige-colored velveteen jodhpurs. It captured the progressive spirit of the time, boldly bent the lines of gender, identity, and cultural dress, and challenged standards for one of society’s most sacred global ceremonies.3

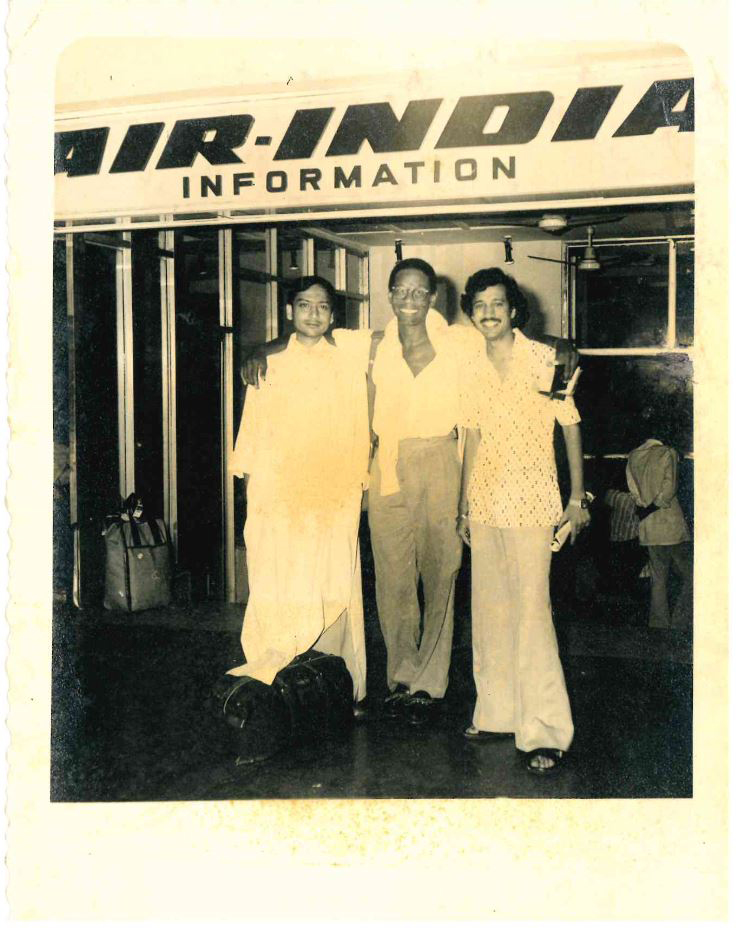

Though little is known about what motivated Smith’s design of the BFM ensemble, possible influences include his experience as a protégé of noted couturier Arthur McGee, whose own non-traditional bridal wear quoted numerous Asian aesthetics, and Smith’s well-documented business and personal interests in India. Smith’s frequent trips to Bombay to oversee design and production with WilliWear manufacturers led to collections that borrowed from traditional Indian garments, such as turbans, cholis, saris, and salwar kameez. His interpretation of dhoti pants became a WilliWear icon.

Like these early WilliWear designs, the BFM ensemble includes an admixture of what were accepted as male and female symbols of dress interpreted through a global lens. The coat resembles a man’s sherwani with a Nehru collar and five functional buttons on the left placket. In the seventies when this jacket was made, placement of buttons on the left side of a garment indicated that it was intended for female wearers. Another symbol of femininity is the jacket’s delicately gathered and flared skirt with a narrow matching belt that, when tied, hangs almost the complete length of the skirt. A decade later, Smith added a headdress by David Madison. Made of pussy willow, statice, and chair caning, this unconventional accessory resembles a woman’s fifties/sixties round, bucket-style or floral pouf hat. The ensemble is completed by masculine pants, more specifically jodhpurs—riding trousers named for a city in the state of Rajasthan in northern India, and historically worn by men of royal or noble birth for weddings, formal occasions, and sporting events.

Like these early WilliWear designs, the BFM ensemble includes an admixture of what were accepted as male and female symbols of dress interpreted through a global lens. The coat resembles a man’s sherwani with a Nehru collar and five functional buttons on the left placket. In the seventies when this jacket was made, placement of buttons on the left side of a garment indicated that it was intended for female wearers. Another symbol of femininity is the jacket’s delicately gathered and flared skirt with a narrow matching belt that, when tied, hangs almost the complete length of the skirt. A decade later, Smith added a headdress by David Madison. Made of pussy willow, statice, and chair caning, this unconventional accessory resembles a woman’s fifties/sixties round, bucket-style or floral pouf hat. The ensemble is completed by masculine pants, more specifically jodhpurs—riding trousers named for a city in the state of Rajasthan in northern India, and historically worn by men of royal or noble birth for weddings, formal occasions, and sporting events.

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Fall 1978 Presentation, 1978

Although WilliWear was recognized for its gender fluidity, Smith typically used the opportunity to design wedding attire for friends and collaborators to indulge in ultra feminine silhouettes with high necks, bare shoulders, and voluminous fishtails layered in silk and tulle. Smith’s rajah wedding ensemble is a rare example of his moving away from Western matrimonial traditions. It represents stylistic, gendered, and ethnic inclusion, personal empowerment, and “control of the self by the wearer,” rather than subversive resistance to the norm.4 This celebration of individuality and freedom of expression is what made Smith one of the most successful designers of his time.

Elaine Nichols is the supervisory curator of culture at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). Nichols has also worked at the South Carolina State Museum as curator of history.

Adrienne Jones is a professor at Pratt Institute. Jones holds degrees in Art Therapy (M.S.), Art Education (B.S.), Fashion Design (A.A.S.), and has won many awards and honors, including being presented with the Innovative Visionary Icon of the Decade by African American Wome in Cinema, in 2015.

Adrienne Jones is a professor at Pratt Institute. Jones holds degrees in Art Therapy (M.S.), Art Education (B.S.), Fashion Design (A.A.S.), and has won many awards and honors, including being presented with the Innovative Visionary Icon of the Decade by African American Wome in Cinema, in 2015.

- Elaine Nichols, “Something Beautiful and Useful: The Work of Lois Kindle Alexander Lane and the Black Fashion Museum Collection at the NMAAHC,” unpublished research paper, April 27, 2015; Renee Minus White, “Harlem Institute of Fashion: Focus on Fashion,” New York Amsterdam News (October 30, 1976), Link.

- Nichols, ibid.

-

Ozeil Fryer Woolcock, “Social Swirl: Black Fashion Museum Founder Was in Atlanta,” Atlanta Daily World (September 20, 1981), Link; BFM Archives, NMAAHC, “A Stitch in Time, 1800−2000,” Box 150, Folder 2, #12.

- Carol Tulloch, “‘My Man, Let Me Pull Your Coat to Something’: Malcolm X,” in The Birth of Cool: Style Narratives of the African Diaspora (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), 127-50.

Attitudes

Horacio Silva

Willi Smith for WilliWear, SUB-Urban Fall 1984 Collection, Photographed by Max Vadukul, 1984

Willi Smith for WilliWear, SUB-Urban Fall 1984 Collection, Photographed by Max Vadukul, 1984Willi Smith, a product of the pop era, was influenced by agenda-setting visionaries like Malcolm McLaren, Andy Warhol, David Bowie, and the clamor and glamour of his beloved Harlem church ladies. His fashion presentations also suggested a love of drag ball culture, a budding scene whose efflorescence coincided with Smith’s move to New York in 1965.

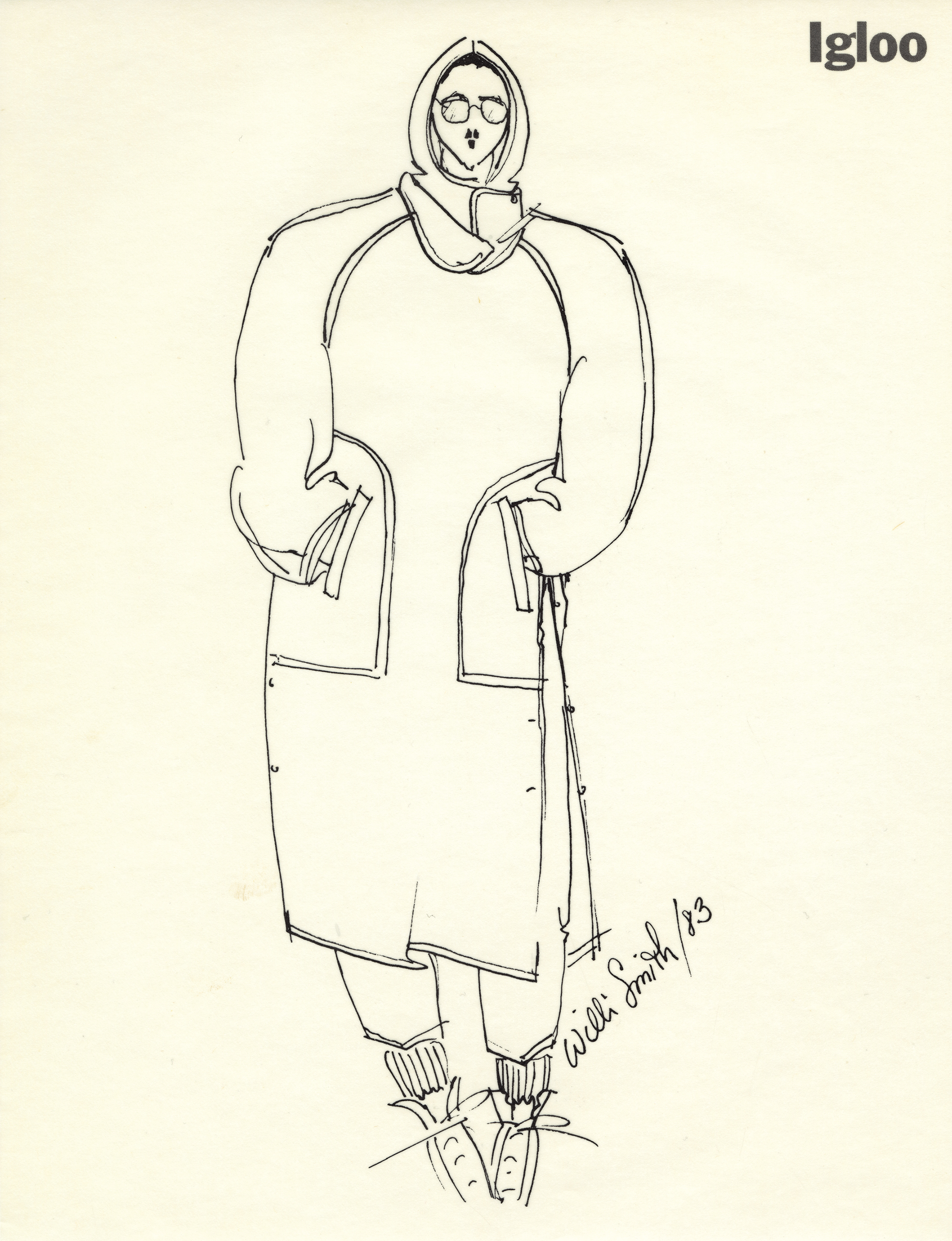

Friends recall his being a Harlem habitué and a regular at drag dives like the Gilded Grape. Fittingly, his collections were often broken down into sections whose nomenclature—Varsity, Work Epic, Renegades, Igloo—bring to mind the categories of the balls. It’s hard not to hear the hyperarticulated, stentorian pronouncements of ball emcees when reading WilliWear program notes: “drill cloth, poplin, corduroy” and “architectural outerwear ready for layering.”

Horacio Silva is the head of content and special projects for Metrograph and is a renowned writer and editor for the world’s most prestigious publications and brands.

Friends recall his being a Harlem habitué and a regular at drag dives like the Gilded Grape. Fittingly, his collections were often broken down into sections whose nomenclature—Varsity, Work Epic, Renegades, Igloo—bring to mind the categories of the balls. It’s hard not to hear the hyperarticulated, stentorian pronouncements of ball emcees when reading WilliWear program notes: “drill cloth, poplin, corduroy” and “architectural outerwear ready for layering.”

Horacio Silva is the head of content and special projects for Metrograph and is a renowned writer and editor for the world’s most prestigious publications and brands.

The Greatest Showman

Horacio Silva

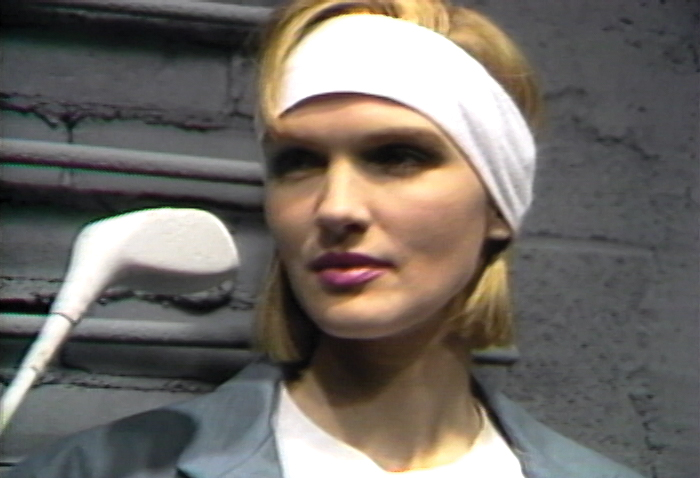

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Fall 1985 Collection, Photographed by Peter Gould, 1985

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Fall 1985 Collection, Photographed by Peter Gould, 1985

A Merlin of Midtown, possessed of the can-do moxie of a Broadway

producer, Willi Smith was a pioneering conjurer of glamour and spectacle whose

influence lives on in the experiential multidisciplinary offerings of today’s genre-bending

designers and cultural producers, from Council of Fashion Designers of America/Vogue

Fashion Fund winner Telfar Clemens to Kanye West and Baz Luhrmann.

Beyond wanting to simply dazzle the eye, Smith was a masterful media manipulator who used every arrow in his quiver to bring his artful message to the masses. In the pre-internet era, before style had highjacked culture, before the star-crossed love affair of the fashion and art worlds, Smith knew full well that these pyrotechnics would help to amplify his message.

WilliWear fashion shows were considered to be more performance art than runway outing, and with good reason. Smith is often compared to his eighties American contemporaries such as Betsey Johnson and Perry Ellis, but in truth he shared more in common with emerging enfants terribles of European fashion Franco Moschino and Thierry Mugler—showmen who, with their increasingly performative runway presentations in Milan and Paris, respectively, were applying the defib paddles to the clinically dead shows of the time.

Beyond wanting to simply dazzle the eye, Smith was a masterful media manipulator who used every arrow in his quiver to bring his artful message to the masses. In the pre-internet era, before style had highjacked culture, before the star-crossed love affair of the fashion and art worlds, Smith knew full well that these pyrotechnics would help to amplify his message.

WilliWear fashion shows were considered to be more performance art than runway outing, and with good reason. Smith is often compared to his eighties American contemporaries such as Betsey Johnson and Perry Ellis, but in truth he shared more in common with emerging enfants terribles of European fashion Franco Moschino and Thierry Mugler—showmen who, with their increasingly performative runway presentations in Milan and Paris, respectively, were applying the defib paddles to the clinically dead shows of the time.

Smith rejected the lifeless legacy of the couture salon with its

soporific music, hippy swagger, and death-stare froideur, preferring instead to

collaborate with artists from all disciplines—most notably with the pioneering

video artists Juan Downey and Nam June Paik—decades before the word

“collaboration” became as hollow as “luxury.”

Though practically unheard of in New York fashion at the time (save for Halston’s shenanigans, which once included Lily Auchincloss’s frying bacon on the runway), Smith’s harnessing of drama and theatrical vision in the pursuit of high-impact fashion moments, his playing limbo with the markers of fashion and art, and his willingness to expand the fashion project into a broad church of creativity are today de rigueur.

Horacio Silva is the head of content and special projects for Metrograph and is a renowned writer and editor for the world’s most prestigious publications and brands.

Though practically unheard of in New York fashion at the time (save for Halston’s shenanigans, which once included Lily Auchincloss’s frying bacon on the runway), Smith’s harnessing of drama and theatrical vision in the pursuit of high-impact fashion moments, his playing limbo with the markers of fashion and art, and his willingness to expand the fashion project into a broad church of creativity are today de rigueur.

Horacio Silva is the head of content and special projects for Metrograph and is a renowned writer and editor for the world’s most prestigious publications and brands.

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring/Summer 1987 Presentation, 1986

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring/Summer 1987 Presentation, 1986

Willi Smith for WilliWear, City Island

Spring 1984 Presentation, 1983

Willi Smith for WilliWear, City Island

Spring 1984 Presentation, 1983

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Fall 1985 Presentation,

Photographed by Peter Gould, 1985

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Street Couture

Fall 1983 Presentation, 1983

Bill T. Jones on Secret Pastures

Interview by Kelly Elaine Navies

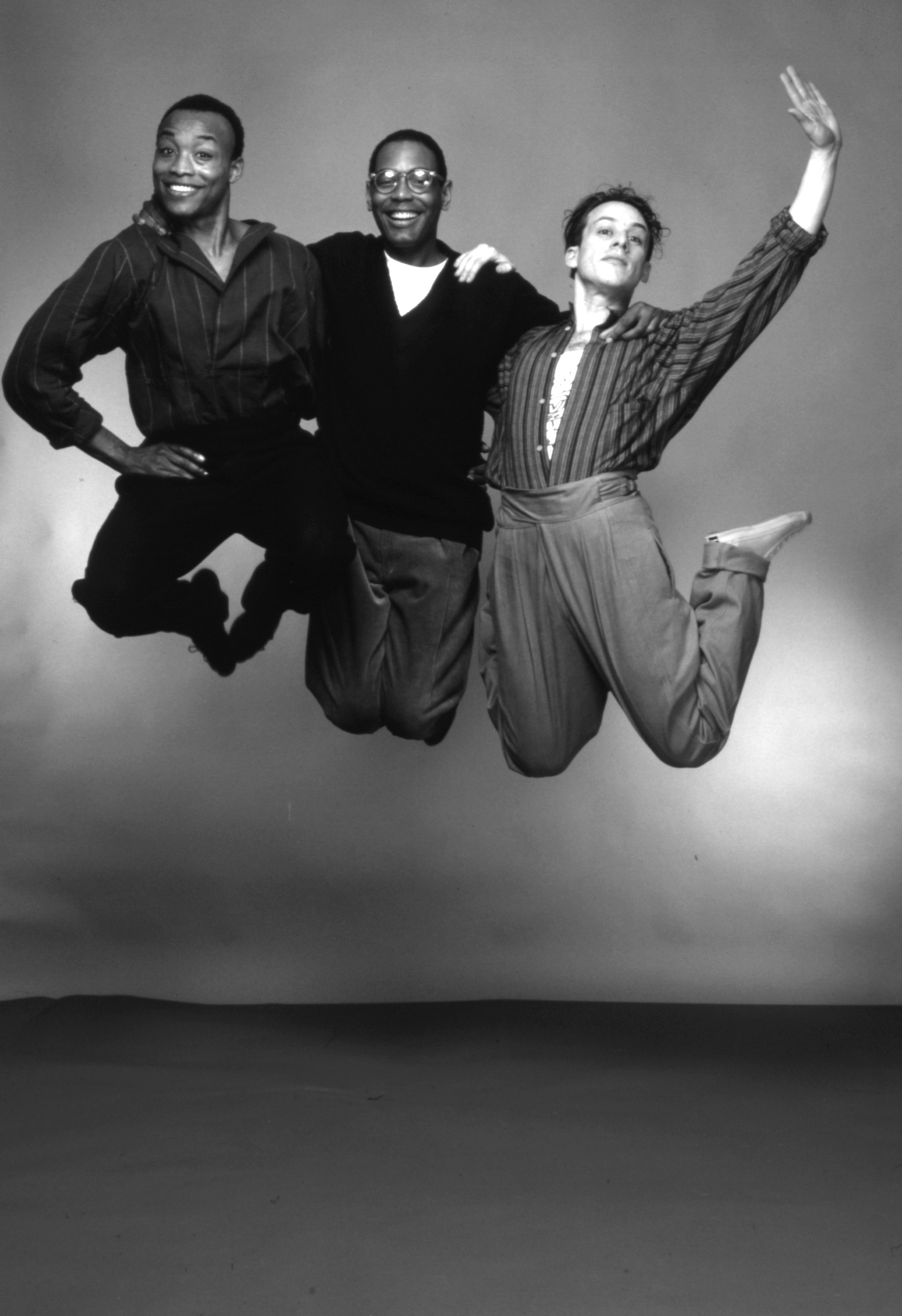

Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane, Promotional Photography for

Secret Pastures, Photographed by Tom Caravaglia, 1984

Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane, Promotional Photography for

Secret Pastures, Photographed by Tom Caravaglia, 1984Bill T. Jones and Willi Smith came together on two

seminal projects: Secret Pastures, a production of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, and Made in

New York, a short film by Les Levine. In both cases, Smith

provided garments that facilitated the action, basic cuts

that moved without overpowering the meaning of the

movement. Beyond their professional exchange, Jones

and Smith experienced similar struggles as creative

visionaries who were Black, gay, and victims of the AIDS

epidemic. This excerpted conversation with Jones was

conducted by Kelly Elaine Navies, museum specialist of

oral history, as part of the National Museum of African

American History and Culture’s Oral History Initiative,

which documents, collects, and preserves oral histories

of iconic elders of African Americana and others who have

shaped the culture in significant ways.

Kelly Elaine Navies:

Bill T. Jones:

Kelly Elaine Navies:

Who brought you and Willi Smith together?

Bill T. Jones:

I don’t remember the first meeting with Willi Smith. I just knew that we were being put together by the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) to work on Secret Pastures for the Next Wave Festival. You know, you were just assigned a costume designer in those days. I remember that Willi was the kind of Black man that I didn’t know. A sophisticated, accomplished, gay Black man. But he was playing that kind of celebrity game, as well. The BAM Producers Council was formed to pull together various successful, glamorous people to support BAM’s growing mission. And the Next Wave brought in performers like me and Arnie Zane, who were just entry level. I mean, had I ever performed at an opera house before or on a big stage? No. They made that possible. And they put Willi into it.

KEN:

And this is how Secret Pastures evolved?BTJ:

Secret Pastures. We thought it was an incredibly sophisticated, tongue-in-cheek title referencing soap operas. You know, As the World Turns. It was going to be called a quasi-narrative, something outlandish like An Island in the Pacific, Artificial Man. I am this kind of hulking Frankenstein-type creature that Arnie, the professor, has made and activated. And he’s going to take me with a group of other people, who were our company. We were gonna explore this island and so on. Keith Haring, who was a friend, sort of said, “Yeah. Yeah.” He was down for anything. He would do the decor. He would make the posters and so on. And Willi knew Keith. Willi was in the scene, and see, Keith, at that point, was probably on the cover of five art magazines—Art in America, Art Forum, ARTnews. He was on all of those covers. Willi was sort of in his milieu. Fashion, you know. And why not the costumes? I think you’ve probably read that the opening night of Secret Pastures was an event. I remember Madonna was there with Andy Warhol. These were Keith’s friends. Then there’s Willi Smith, who was doing the costumes. So there was a fashion angle to it. And our company, who had just been rolling around on the stage, doing this kind of odd gymnastics with a formatless attention, we were suddenly being photographed and on the cover of Dance Magazine. It all happened so fast.

KEN:

BTJ:

What do you remember about the interactions with Willi Smith and Keith Haring and the collaboration overall?

BTJ:

In addition to designing the costumes, Willi brought in Marcel Fieve, who was Belgian and a very adventurous hairdresser. Nobody in the dance world was thinking about hair and makeup except Twyla Tharp, and Twyla was an outlier. She didn’t want anything to do with the downtown world, and the downtown world didn’t want anything more to do with her since she’d already done that, in her mind, ten or fifteen years before. I remember that the opening night at BAM, Keith and Tim Carr [the programming consultant for Next Wave] were so scandalous, because the program they had printed up said “Hair and Makeup by Marcel Fieve.” So everybody who opened the program just fell on the floor and said, “Oh. Look at that. That says it all. ‘Hair and makeup.’ They’ve lost their soul. Our Bill and Arnie have really lost their soul.” ’Cause we’re doing hair and makeup. But, you know, souls are lost and found. And we were darlings, but we were also very ambitious.

KEN:

BTJ:

Were you attracted to Willi Smith’s style? Did you wear WilliWear?

BTJ:

I was attracted to the concept of WilliWear—that he was trying to look at the street and make fashion. That he would wanna work with us. That he was a successful man. Long stretch limousine. But he had a drug problem. He’d just cleaned up from it, I believe. And we would talk about things. I had never had a Black friend I could talk to about “What does it mean?” “Why are you in an interracial relationship?” And I remember him saying to me—I respect his memory, but I think he would appreciate me telling this story—“Look, man. You know, I had a Black lover. I did. But it turned into colored business. In the middle of the night, the police were coming. Somebody’s been called. We’re fighting and so on and so forth. You know?” And then he said, “And I wasn’t interested in being a white princess. ’Cause, you know, let’s face it. In a lot of those relationships, I was like the white guys. I was more educated, had more money. So you find some young dude, Black dude, and you become the white princess, and he becomes your stud.” And he said he wasn’t interested in that. Very strong language. Oh, yeah. It was wonderful.

KEN:

BTJ:

KEN:

BTJ:

You connected about being two Black gay men within the arts scene?

BTJ:

We didn’t use that language. No. But that’s what it was. We knew that’s what it was. You know? We knew that we no longer had to be ashamed. But what was the drug addiction about? What was this running to the baths about? That was like trying to taste something? And then AIDS.

KEN:

Yes. Did you talk about AIDS?

BTJ:

I remember we had been seeing Willi. Secret Pastures had happened. We were still hanging out with Keith and all. And it was a Saturday morning, and Arnie was concerned, because he had begun to show some signs of being HIV-positive. And he was on a macrobiotic diet and so on and so forth. He and I were both tested in ’85. In ’86, he had this bump here, which actually was the beginning of—not leukemia, but lymphoma. And that was in May. I remember very well. May of ’86. And he died in March of ’88. Those two years was doctors, doctors, doctors. Sometimes, seven doctors a week. Different doctors, specialists. Different treatments and all. But Willi . . .

KEN:

BTJ:

KEN:

BTJ:

KEN:

BTJ:

He passed away in ’87. The year before.

BTJ:

Saturday morning, Arnie comes downstairs, and I come down. And Arnie is in front of the TV. And he sees a little tiny picture. “Designer Willi Smith has died.” And we knew the rest of us all were gonna die. We all would be dead.

KEN:

You knew it was AIDS?

BTJ:

Oh, we all knew.

KEN:

Because at first, they didn’t discuss that in the newspaper.

BTJ:

Oh, no, they didn’t. They didn’t. They didn’t even say it about Arnie either. But we all knew what was going on. And I think we expected we’re all gonna die. You know? And it was a terrifying moment. But Willi was the first one. And so Willi died in ’87. Arnie died in March of ’88. Keith Haring died in 1990. Boom boom boom.

Bill T. Jones, Willi Smith, and Arnie Zane, Photographed

by Jack Mitchell, 1984

Bill T. Jones, Willi Smith, and Arnie Zane, Photographed

by Jack Mitchell, 1984KEN:

BTJ:

KEN:

Hearing that, what you went through and the losses that you experienced in those years, it’s not a surprise that you created Still/Here.

BTJ:

Still/Here was in ’94, now that I think about it. ’84, Secret Pastures. ’94, Still/Here. That’s ten years. Right? Yeah. Still/Here was ’94. Well, I was trying

to roll with it. I still saw myself as a serious artist, a movement-based artist. The body has a poetry to it. This is the same sense of the body when I discovered dance ten years before in State University of New York in Binghamton. And now, how do you put that together with something big like the tragedy of death? And then, a guilty disease. Remember Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor?

KEN:

Yes.

Saturday morning, Arnie comes downstairs, and I come down. And Arnie is in front of the TV. And he sees a little tiny picture. “Designer Willi Smith has died.” And we knew the rest of us all were gonna die. We all would be dead.

BTJ:

KEN:

BTJ:

In which she talks about tuberculosis in the nineteenth century being associated with courtesans and people who lived fast? And now, here we are, faced with another guilty disease, and people are dying every day. Willi dies. And Willi had been so fashionable and so fabulous, and he had stopped doing drugs. He was trying to clean his act up. And he still got caught. I understood something about Willi’s pain. Had there ever been a Black designer who achieved this sort of fame that Willi had? After he won the Coty Award [in 1983], I remember him complaining that people didn’t think he had craft. He said to them, “You all don’t think I know fabric. ’Cause, you know, he used cotton fabrics, affordable fabrics, but they were fun fabrics. And he was making them for the public, and for people who were poor. He didn’t want to go the couture route.

KEN:

Right.

BTJ:

It was ready-to-wear. He had to be “I’m a serious designer. I know what you think design is. But I’m also a contemporary maker. And I’m really trying to make from the street, make from my Black experience.” And so on. So that’s what I appreciated about Willi. He was a man with a lot of sadness. He was often misunderstood.

KEN:

BTJ:

What do you hope people learn about Willi Smith’s work and about your collaboration together?

BTJ:

Willi was a generous man and had a lot of love. I think he was a bit cautious. That whole conversation about interracial relationships? I think he understood that there was a price we had to pay. We could not find our companions among the ranks of Black people. And that said something about who we were, but also something about what the world saw. You know, there used to be this discussion about Black men—straight men would get to a certain level, then their partners would be white women. So was that self-loathing, or was it about education and cultural references? He was trying to find his way through, and he was trying to succeed as a businessman. And Laurie Mallet was very, very important. A decent woman and very ambitious. What would I like to remember? Remember him as being generous. Remember him as being self-made, as we all had to be—making it up. Looking for authenticity. Having to, in some ways, play a role that maybe a young designer doesn’t have to play. Well, a young designer of color, ’cause there are so many more now. We recognized each other, but our disciplines were so different, and our understandings of the world were so different. But I think that he had a lot of faith in the future, and I think he truly believed in beauty. I think he participated in politics through how he lived and what he made. And I think he really was a human being, first and foremost. I would dare say even before being a Black person. He was a maker—a human maker. So his friends were a wide variety of people, and he was not afraid or intimidated by the serious avant-garde. He could come into it. I don’t know how he felt in the fashion world, but he moved with ease in the art world, which was to our advantage.

Kelly Elaine Navies is the Museum Specialist in Oral History for the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Bill T. Jones, cofounder of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, is a multitalented artist, choreographer, dancer, theater director, and writer who has received major honors, including a 1994 MacArthur “Genius” Award, Kennedy Center Honors in 2010, a 2013 National Medal of Arts, and the Human Rights Campaign’s 2016 Visibility Award.

Real Clothes for Real Dance

Tiffany E. Barber

He had great disdain for anything that made him sweat— other than dancing.1

Polly Rayner

Willi Smith’s first runway shows for WilliWear took place at lofts, theaters, and galleries in downtown Manhattan in 1978, combining two of the designer’s favorite things: people and dance. A cohort of dancers doubled as models for these events, showcasing Smith’s innovative approach to clothes and performance to crowds of fashion and art world insiders. A funky balance of form, function, and play, his now iconic workwear jumpsuits with sailor collars and lightweight cotton separates defied social norms concerning gender and sexuality as well as those associated with high fashion. For Smith, fashion was more than a lifestyle. It was real people. It was unstructured movement. These characteristics likewise motivated the designer’s pioneering artistic collaborations, from modern and postmodern dance to video art. Against the backdrop of seventies disco and the ostentatious pop and pomp of the eighties, Smith’s designs for the everyday and the stage represented a different kind of dynamism where contemporary public life and performance not only intersected; they commingled and were co-constitutive.

Dancer-choreographer Dianne McIntyre’s The Lost Sun (1973) and Deep South Suite (1976) were the first of many collaborations Smith would pursue in the years preceding and immediately following the launch and meteoric success of his label. Both dances interweave “high” and “low” cultural forms. Set to pianist Gene Casey’s Antediluvian Mystery, The Lost Sun premiered at the Clark Center for the Performing Arts in New York on January 28, 1973, and featured six dancers whose leg and arm extensions, torso contractions, high jumps, and turns epitomized the virtuosity McIntyre strove to convey in her early work. Smith’s simple yet elegant costumes for The Lost Sun echoed the dancers’ expressivity. The jersey-knit half-sleeve bolero capes, two-piece shirt and skirt sets, turbans, and billowing pants wrapped at the ankle flowed with abandon just as the dancers did. All in white, beige, and yellow, the costume separates, along with their fluid silhouettes and tailored details, served as prototypes for the looks Smith would eventually mass-produce.

Polly Rayner

Willi Smith’s first runway shows for WilliWear took place at lofts, theaters, and galleries in downtown Manhattan in 1978, combining two of the designer’s favorite things: people and dance. A cohort of dancers doubled as models for these events, showcasing Smith’s innovative approach to clothes and performance to crowds of fashion and art world insiders. A funky balance of form, function, and play, his now iconic workwear jumpsuits with sailor collars and lightweight cotton separates defied social norms concerning gender and sexuality as well as those associated with high fashion. For Smith, fashion was more than a lifestyle. It was real people. It was unstructured movement. These characteristics likewise motivated the designer’s pioneering artistic collaborations, from modern and postmodern dance to video art. Against the backdrop of seventies disco and the ostentatious pop and pomp of the eighties, Smith’s designs for the everyday and the stage represented a different kind of dynamism where contemporary public life and performance not only intersected; they commingled and were co-constitutive.

Dancer-choreographer Dianne McIntyre’s The Lost Sun (1973) and Deep South Suite (1976) were the first of many collaborations Smith would pursue in the years preceding and immediately following the launch and meteoric success of his label. Both dances interweave “high” and “low” cultural forms. Set to pianist Gene Casey’s Antediluvian Mystery, The Lost Sun premiered at the Clark Center for the Performing Arts in New York on January 28, 1973, and featured six dancers whose leg and arm extensions, torso contractions, high jumps, and turns epitomized the virtuosity McIntyre strove to convey in her early work. Smith’s simple yet elegant costumes for The Lost Sun echoed the dancers’ expressivity. The jersey-knit half-sleeve bolero capes, two-piece shirt and skirt sets, turbans, and billowing pants wrapped at the ankle flowed with abandon just as the dancers did. All in white, beige, and yellow, the costume separates, along with their fluid silhouettes and tailored details, served as prototypes for the looks Smith would eventually mass-produce.

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring 1979 Presentation, 1978

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring 1979 Presentation, 1978

The costumes and choreography for Deep South Suite, a signature piece named after Duke Ellington’s jazz composition of the same name, were inspired by what Smith and McIntyre imagined Black life to be in the American South. Alvin Ailey, pioneer of African American concert dance, invited McIntyre to make the suite for his 1976 Duke Ellington Festival.2 Vivifying the programmatic notes Ellington penned for the composition, McIntyre’s expressive choreography builds with the music across the dance’s four sections. Seven dancers intermix leg extensions, pirouettes, and movements drawn from modern dance techniques with hip rolls and shimmies performed in juke joints and dance halls. In each section, the dancers’ movements closely relate to and elaborate various parts and pitches of the multilayered musical score, moving from joyous camaraderie in the first section to the somber effects of racial violence in the second section. The third section, a duet, explores the possibilities of interracial love, and the final section circles back to the ensemble dancing and waving as a train conductor passes by the crowd. McIntyre saw Deep South Suite as not only an extension of the music but also as an added element necessary for completing Ellington’s orchestration. At various moments, the dancers fall to the ground in unison, reacting to an unseen force. Putting into motion the realities of Black life in the South, the dancers slump, shimmy, jump, partner, and extend their arms and legs high above their heads. Smith’s free flowing skirts, blouses, bandanas, and pants accentuate these movements and the desire for new opportunities.

Smith’s design sensibility in these early creative exchanges was the perfect complement to McIntyre’s explorations of the synergy between dance and jazz music. As an undergraduate at Ohio State University, McIntyre studied structured improvisation with Judith Dunn, a founding member of Judson Dance Theater, and Bill Dixon, a well-known free jazz musician. Structured improvisation often takes the shape of a score—a set of prompts that encourages organized yet open, fluid movement and exploration, the outcomes of which are not predetermined. For Dunn and Dixon, structured improvisation was the grounds for formal and social experimentation. “In addition to creating striking improvised works,” dance scholar Danielle Goldman outlines, the pair’s “collaborations explored and openly acknowledged relations between Black traditions of improvised music and the rather white world of postmodern dance.”3 Dunn’s improvised work incorporated quotidian movement and chance procedures that spanned rolling dice to determine when and where dancers would enter and exit the stage and leaving parts of her compositions open to the performers’ own choices. Dixon, on the other hand, found chance operations limiting and preferred freedom and sponta- neity in the moment. Both, however, assigned dance and music equal value, refusing to see them as independent elements that exist in a hierarchical relationship.

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Summer 1978 Presentation, 1978

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Summer 1978 Presentation, 1978McIntyre’s work elaborates Dunn and Dixon’s process by underscoring the social aspects of dance. For McIntyre, dance is not presentational. She encourages dancers to relinquish their personae in order to inhabit the interior of her choreography, which originates from two extreme ways of working. McIntyre’s dances are either totally improvised or the result of stylized choreography created and set in rehearsals. At times, the movement and the music simultaneously affect one another, generating a unique work of art in the moment. Upon moving to New York in 1970, McIntyre further developed her signature style. She associated with jazz musicians from the Master Brotherhood collective and incorporated Black social dances such as the jitterbug, the shag, and the Charleston into her work. Louise Roberts, director of the Clark Center, mentored her in these beginning stages, giving the budding choreographer free space to rehearse her early dances. Roberts produced McIntyre’s first formal dance concert at the Clark and helped McIntyre establish Sounds in Motion in 1972. During this fruitful period, McIntyre facilitated cross-disciplinary conversations between visual artists, dancers, musicians, critics, and designers, “even though design was somewhat peripheral,” the dancer choreographer remembers.4 Reflecting on what it was like to come of age as artists in the seventies and eighties, she states, “For us, it was all part of the same mix. . . [Willi] never set himself apart; he wanted to be part of the art. . . It was the way things flowed at the time. It was cross-fertilization.”5 Influenced by civil rights struggles and the Black arts movement, McIntyre’s informal convenings paralleled Smith’s collaborative spirit, which soon found new outlets for expression.

Bernadine Jennings and Leon Brown in Deep South Suite,

Choreographed by Dianne McIntyre, Photographed by Johan Elbers, 1976

Bernadine Jennings and Leon Brown in Deep South Suite,

Choreographed by Dianne McIntyre, Photographed by Johan Elbers, 1976

The eighties afforded Smith exciting opportunities as the designer’s brand expanded. Along with his success, Smith’s aesthetic sense matured, as did his interdisciplinary vision. The designer and his partner Laurie Mallet launched a production division, WilliWear Productions, to focus on large-scale collaborations with several of the era’s most compelling contemporary artists. Reflecting on his ambitions during this time, Smith exclaimed, “I want to branch out, I want to be everywhere. . . I want to conquer the world!”6 Notably, dance remained central to the designer’s evolving vision and patronage. In 1983, he funded the premiere of Trisha Brown, Robert Rauschenberg, and Laurie Anderson’s Set and Reset at Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM), with the next year proving even more monumental. On May 16, 1984, WilliWear produced Artventure, a gala benefiting the Public Art Fund in New York. At the event, the designer premiered Made in New York (1984), video artist Les Levine’s funky, offbeat homage to the city that never sleeps starring Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane, and sold his new line of artist T shirts. A month later, McIntyre premiered one of her most memorable dances, Take-Off From a Forced Landing, in honor of her mother who in 1939 entered a government aviation program and became one of the first Black women to be trained as a pilot. For the piece, Smith dressed the eight dancers in goggles and a reworked version of his lightweight cotton jumpsuits. Smith first developed this clothing concept for Digits Sportswear, and the uniform repeatedly appeared in his WilliWear collections and costume designs. In November and December later that year, he designed costumes for Secret Pastures, a landmark piece that again featured Jones and Zane, and funded BAM’s 1984 revival of Philip Glass, Robert Wilson, and Lucinda Child’s Einstein on the Beach (1976), a five-hour-long opera in four acts. Both works revolutionized live theater. 7

Secret Pastures epitomizes Smith’s desires to work beyond fashion. The ninety-minute piece premiered at BAM’s Next Wave Festival on November 15, 1984. Featuring a compendium of collaborators working across concert dance and pop art, the piece animates the concept of gesamtkunstwerk—“the total work of art.” Jones and Zane choreographed the movement; Peter Gordon composed the music; Marcel Fieve styled makeup and hair; Keith Haring designed the set elements; and Smith created the costumes. Jones as fabricated man, Zane as the professor, and eleven ensemble characters enliven Secret Pastures’s nonlinear narrative about the divide between primitive and modern experience. The professor and the ensemble execute angular, sharp, and sexually evocative movements, punctuating Gordon’s percussive, punk-inflected score and Haring’s iconographic homoerotic drawings on stage.8 Smith’s asymmetrical frocks and jumpsuits worn over undergarments in neutral colors, swing coats, and signature pants—baggy with a high, wrapped waist—encourage freedom in motion while Jones’s primordial figure, dressed in a unitard, moves awkwardly yet fluidly. In a duet with Zane, Jones learns to walk, dance, and gyrate as Zane inspects and manipulates his limbs. As the piece progresses, the narrative becomes a pretext for dancing, and the choreography becomes more sexually explicit. At one point, the dancers, now wearing bright-colored, tight-fitting athletic wear, transpose Haring’s drawings into a tableau: in a line of intertwined bodies, a dancer’s head crouches in between another dancer’s legs; one appears to bite another’s neck; and yet another dancer throws their head back in ecstasy.

Smith’s unisex, interchangeable costumes designed to be switched from dancer to dancer contrast with Secret Pastures’s sexual charge. His “freewheeling” designs, as he described them,9 instead emphasize form, vitality, and unrestrained movement, all of which Jones and Zane, personal and professional partners, exploited in their own identity-based work of the seventies and eighties. Jones’s interest in movement and speech fused with the visual design sensibility Zane drew from his work as a photographer and experimental filmmaker. The physical contrast between Jones (tall, African American, gracefully athletic) and Zane (short, Jewish, quick, and wiry) also informed the pair’s shared creativity. After attending Lois Welk’s contact improvisation workshop at SUNY Brockport, collaboration became a central component of their choreographic process. Between 1974 and 1979 in Binghamton, New York, the duo was part of American Dance Asylum (ADA) along with Welk and another dancer, Jill Becker. To develop their individual and collective works, the members of ADA employed a process whereby each member informed the activities of the others. Though formative, Jones and Zane had outgrown ADA by 1979. Wanting to live in an area more supportive of both their art and their identity as an interracial gay couple, the pair moved to Rockland County, New York, where they continued to make dances together until Zane’s death in 1988.10 Like Dunn and Dixon, improvisation, and dance more broadly, provided Jones and Zane with techniques for breaking down taboo boundaries between form and identity on the one hand and race, sexuality, and age on the other. Against the grain of aesthetic and social expectations regarding which bodies can and should dance, male-to-male intimacy, and interracial partnerships, the duo worked to be on stage together-intertwining their bodies, lifting and carrying each other across stage, striving for more.11

Smith’s unisex, interchangeable costumes designed to be switched from dancer to dancer contrast with Secret Pastures’s sexual charge. His “freewheeling” designs, as he described them,9 instead emphasize form, vitality, and unrestrained movement, all of which Jones and Zane, personal and professional partners, exploited in their own identity-based work of the seventies and eighties. Jones’s interest in movement and speech fused with the visual design sensibility Zane drew from his work as a photographer and experimental filmmaker. The physical contrast between Jones (tall, African American, gracefully athletic) and Zane (short, Jewish, quick, and wiry) also informed the pair’s shared creativity. After attending Lois Welk’s contact improvisation workshop at SUNY Brockport, collaboration became a central component of their choreographic process. Between 1974 and 1979 in Binghamton, New York, the duo was part of American Dance Asylum (ADA) along with Welk and another dancer, Jill Becker. To develop their individual and collective works, the members of ADA employed a process whereby each member informed the activities of the others. Though formative, Jones and Zane had outgrown ADA by 1979. Wanting to live in an area more supportive of both their art and their identity as an interracial gay couple, the pair moved to Rockland County, New York, where they continued to make dances together until Zane’s death in 1988.10 Like Dunn and Dixon, improvisation, and dance more broadly, provided Jones and Zane with techniques for breaking down taboo boundaries between form and identity on the one hand and race, sexuality, and age on the other. Against the grain of aesthetic and social expectations regarding which bodies can and should dance, male-to-male intimacy, and interracial partnerships, the duo worked to be on stage together-intertwining their bodies, lifting and carrying each other across stage, striving for more.11

Secret Pastures at Brooklyn Academy of Music, Choreographed by Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, Music composed by Peter Gordon, Set designed by Keith Haring, Costumes designed by Willi Smith, Photographed by Tom Caravaglia, 1984

Secret Pastures at Brooklyn Academy of Music, Choreographed by Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, Music composed by Peter Gordon, Set designed by Keith Haring, Costumes designed by Willi Smith, Photographed by Tom Caravaglia, 1984

Secret Pastures at Brooklyn Academy of Music, Choreographed by Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, Music composed by Peter Gordon, Set designed by Keith Haring, Costumes designed by Willi Smith, Photographed by Tom Caravaglia, 1984

For McIntyre, Jones, and Zane, dance and meaningful collaboration engendered radical acts of freedom. They each worked within and beyond concert dance’s constraints to interrogate staid notions of embodiment, culture, and form. By bridging dance with Black sound, improvisation, autobiography, and cross-racial intimacy, McIntyre, Jones, and Zane contested the confines of modern dance practice and theory as well as the post- modern dance world’s overwhelming whiteness. Smith relatedly sought to make clothes for various bodies and shapes unbound by racial and sexual pathologies, even as his identity and lived experiences deeply informed his work. Like Jones, who “rankled at being called a ‘Black artist,’” Smith saw himself as more than simply “a Black designer.”12 Smith’s approach to making clothes, what cultural critic Hilton Als calls “the designer’s democratic urge,” was interdisciplinary from the start, and he and his collaborators were each on the cutting edge of their respective fields.13 Smith infused his separates with whimsy and irreverence, humor and exuberance, quali- ties also present in his designs for dance. Ultimately, his costumes articulate a novel theatrical style on par with the choreographic ethos of McIntyre, Jones, and Zane—“real” clothes for “real” dance that transgressed the rules of the avant-garde. In so doing, Smith and his collaborators initiated new modes of artistic expression and unrestricted movement at the forefront of postmodern art and design.

Tiffany E. Barber is a scholar, curator, and writer of twentieth- and twenty-first-century visual art, new media, and performance. Her work focuses on artists of the Black diaspora working in the United States and the broader Atlantic world.

Tiffany E. Barber is a scholar, curator, and writer of twentieth- and twenty-first-century visual art, new media, and performance. Her work focuses on artists of the Black diaspora working in the United States and the broader Atlantic world.

- Polly Rayner, “WilliWear Designer Creates ‘Basic Clothes with a Sense of Humor,” Morning Call (October 21, 1984), accessed July 15, 2019, Link.

- Alvin Ailey’s Duke Ellington Festival ran from August 10 to 15, 1976, at Lincoln Center’s New York State Theater. The festival was planned to coincide with the bicentennial of the USA. Ailey selected the music for McIntyre’s piece.

- Danielle Goldman, I Want to Be Ready: Improvised Dance as a Practice of Freedom (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2010), 62.

- Dianne McIntyre (dancer-choreographer) interviewed by Alexandra Cunningham Cameron and Julie Pastor, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, NY, 2019, unpublished recording.

- Ibid.

- Smith quoted in Rayner, Link.

- Dance continued to energize Smith’s interdisciplinary approach to design and performance in the years between 1984 and his death in 1987. One notable example of this is Expedition (1985), which featured members of the National Ballet of Senegal.

- Between 1982 and 1984, Bill T. Jones collaborated with Keith Haring on three different projects. Long Distance, performed at The Kitchen in 1982, featured Jones dancing to the sounds of Haring’s brushstrokes as he simultaneously painted the backdrop in situ. Next, Haring’s white-line drawings adorned Jones’s naked body in a series of photographs that Tseng Kwong Chi took in 1983. The third project was Secret Pastures.

- Smith quoted in Nancy Vreeland, “Dance & Fashion,”

Dance (October 1984): 75.

- Jones and Zane formed the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company in 1982.

- Goldman makes a similar claim about Dunn and Dixon. See Goldman’s “We Insist! Seeing Music and Hearing Dance,” in I Want to Be Ready: Improvised Dance as a Practice of Freedom (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2010), 69.

- See Bill T. Jones with Peggy Gillespie, Last Night on Earth (New York: Pantheon Books, 1995), 164.

- Hilton Als, “Willi Smith, 1948–87” Village Voice (April 28, 1987).

Feast or Fashion

Horacio Silva

Miralda, Inspiration for Dressing Tables, 1983

Miralda, Inspiration for Dressing Tables, 1983

To celebrate his Coty Award win in 1983, Willi Smith tapped Miralda, the Spanish food artist known for installations such as Edible Landscape, Sangria, and Moveable Feast, to cook up something special in the designer’s showroom. On the menu at Miralda’s Dressing Tables, as the event was billed: three stations shaped to represent a jumpsuit, pants, and a shirt (Smith’s outfit combination of choice), with three different dressings—mustard, ketchup, and mayonnaise.

Generously seasoned with concept, each table had a special color code for drinks that were placed on small mirrors: red drink for chicken with mustard, green drink for asparagus and mayonnaise, blue drink for shrimp with ketchup. A bit hard to swallow by today’s tastes, but the participatory food performance predates the private event-as-food-for-thought efforts of artist Jennifer Rubell by at least two decades. According to the Daily News Record, invitees initially “stared suspiciously at the tables wondering what to do.” After realizing the date and signed “mini-couture” boxes they were given contained shrimp, chicken, and asparagus, guests ate it up with a spoon.

Horacio Silva is the head of content and special projects for Metrograph and is a renowned writer and editor for the world’s most prestigious publications and brands.