Future Crossings

Brendan Fernandes

Willi Smith on Set, Expedition, Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring 1986

Collection, Photographed by Mark Bozek, Dakar, Senegal, 1985

Willi Smith on Set, Expedition, Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring 1986

Collection, Photographed by Mark Bozek, Dakar, Senegal, 1985

In 1984, when I was five years old, my family traveled from Nairobi, Kenya, to Calgary, Canada. Leaving the African continent for the first time to visit family in North America, my mother had my two sisters, father, and me dressed in matching tailored outfits: khaki suits à la safari with details in plaid—an ode to what we understood as Western style. We didn’t have a lot of money, but the question of how we were going to express our “African” selves in North America was important for us. At that early age, with few resources and clever tailoring, my mother instilled in my sisters and me the value of self-presentation. Today the question of how I present myself as a queer, Brown, border-crossing man is of serious personal and physical consequence.

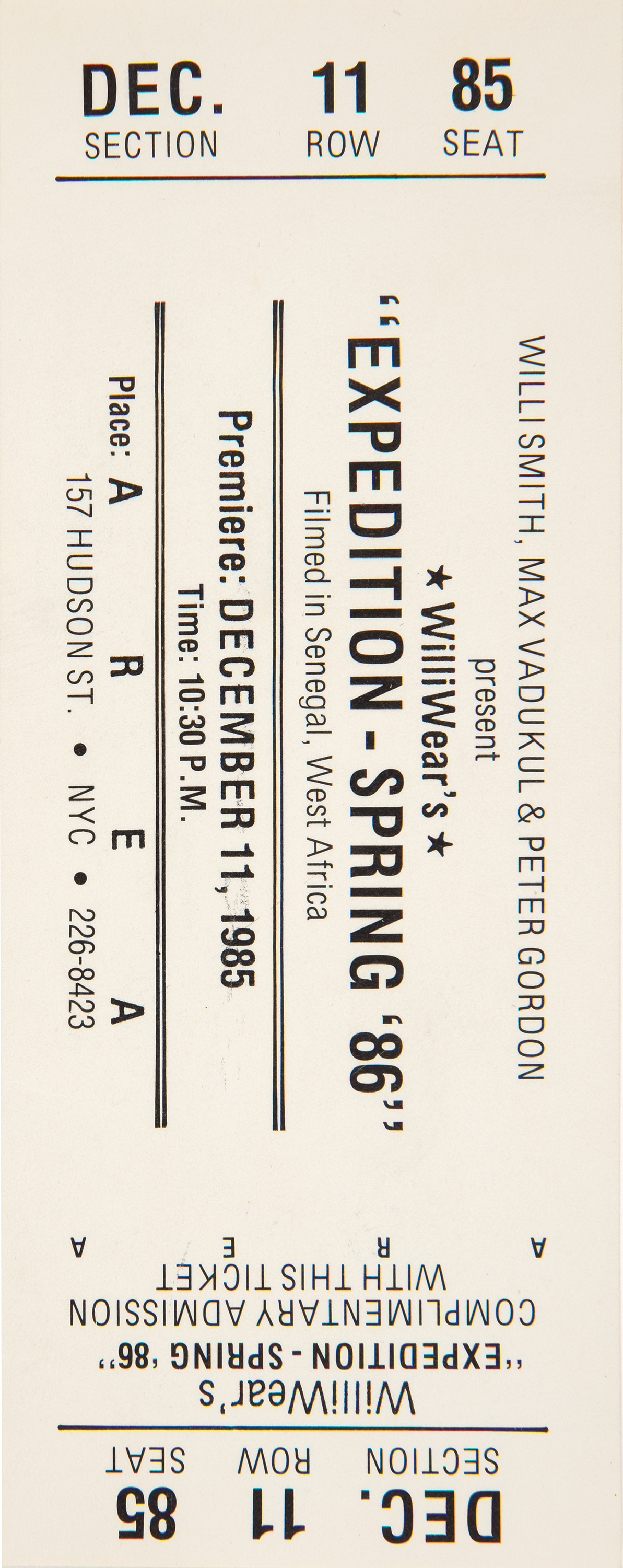

One year after my family’s journey, Willi Smith produced Expedition (1985), an experimental short film that could be considered the inverse of my family’s experience. Shot by Kenyan-born photographer Max Vadukul with a score by Peter Gordon, the film follows Chicky, a caricature of a white man, as he travels in “Afrique,” the nonexistent place that the African continent occupies in the Western imagination. As he is subjected to an over-the-top border inspection upon arrival, a family of WilliWear models escape from his suitcase and begin to vogue, model, mischief, and make for a bathroom break in Smith’s brightly patterned fall collection. The film is a camp-fest reversal of stereotypes. The white man is made the outsider, and Smith pokes critical fun at the perception of African bodies as refugees or smuggled goods. Subverting the cliché of cross-border experience with humor may have been exactly what my mother had in mind with her own stylized border-crossing.

One year after my family’s journey, Willi Smith produced Expedition (1985), an experimental short film that could be considered the inverse of my family’s experience. Shot by Kenyan-born photographer Max Vadukul with a score by Peter Gordon, the film follows Chicky, a caricature of a white man, as he travels in “Afrique,” the nonexistent place that the African continent occupies in the Western imagination. As he is subjected to an over-the-top border inspection upon arrival, a family of WilliWear models escape from his suitcase and begin to vogue, model, mischief, and make for a bathroom break in Smith’s brightly patterned fall collection. The film is a camp-fest reversal of stereotypes. The white man is made the outsider, and Smith pokes critical fun at the perception of African bodies as refugees or smuggled goods. Subverting the cliché of cross-border experience with humor may have been exactly what my mother had in mind with her own stylized border-crossing.

What we can take from these images is that self-presentation changes our claim to space. Smith’s spectacular WilliWear runway shows created space for individual expression. Taking street fashions and church tailoring from Harlem to international runways, Smith’s ethos created new spaces for the people who wore his collections. Ever conscious of the kinds of spaces he designed for, Smith emphasized that WilliWear needed to be affordable, saying that his mother and grandmother taught him that “you didn’t have to be rich to look good . . . good clothes don’t have to be expensive.”1 He intended to change people’s perceptions of themselves by giving them the tools—the clothes—to both present themselves and see themselves presented in new spaces.

However, as we can see in Expedition, Smith’s work went further than expanding representation. His garments challenged space and questioned its occupancy. The silhouettes and bold color draw attention, creating a kind of hypervisibility. In the fictional world of Expedition, this hypervisibility functions as a kind of camouflage, whereby the WilliWearers go unnoticed, but their plain-clothes porter is questioned and hindered at every stage of his journey. Smith’s work suggests that while mere visibility can be humiliating, even dangerous, hypervisibility can be an effective strategy for both subversion and survival.

Another quote from Smith resonates deeply with my own experience of clothing: “In my house growing up, we had more clothes than food; the emphasis was on how you looked.’’2 Clothing is kin to survival. He suggests a powerful principle—in a world that emphasizes appearances, social mobility is available to those who can “look” a certain way. The craft of making clothes, then, is a kind of social engineering. My grandmother was a seamstress. She made many of the clothes we wore and through this she taught my mother that how you present yourself to the world can change the way the world receives you.

My mother passed this intelligence on to my sisters and me, and we have since passed this down to the next generation. Appearance can allow you to position yourself regardless of class and capital. Conversely, when you do this, the systems of class and capital become a lot more porous than they at first appear.

However, as we can see in Expedition, Smith’s work went further than expanding representation. His garments challenged space and questioned its occupancy. The silhouettes and bold color draw attention, creating a kind of hypervisibility. In the fictional world of Expedition, this hypervisibility functions as a kind of camouflage, whereby the WilliWearers go unnoticed, but their plain-clothes porter is questioned and hindered at every stage of his journey. Smith’s work suggests that while mere visibility can be humiliating, even dangerous, hypervisibility can be an effective strategy for both subversion and survival.

Another quote from Smith resonates deeply with my own experience of clothing: “In my house growing up, we had more clothes than food; the emphasis was on how you looked.’’2 Clothing is kin to survival. He suggests a powerful principle—in a world that emphasizes appearances, social mobility is available to those who can “look” a certain way. The craft of making clothes, then, is a kind of social engineering. My grandmother was a seamstress. She made many of the clothes we wore and through this she taught my mother that how you present yourself to the world can change the way the world receives you.

My mother passed this intelligence on to my sisters and me, and we have since passed this down to the next generation. Appearance can allow you to position yourself regardless of class and capital. Conversely, when you do this, the systems of class and capital become a lot more porous than they at first appear.

My definition of queerness goes beyond gender and sexuality. Queer is about how we perceive and position ourselves in relation to hegemonies. In this sense, Smith queered space. He played with the borders and loosened the boundaries.

Theatre National Daniel Sorano Dancers on Set, Expedition, Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring 1986 Collection, Photographed by Mark Bozek, Dakar, Senegal, 1985

Theatre National Daniel Sorano Dancers on Set, Expedition, Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring 1986 Collection, Photographed by Mark Bozek, Dakar, Senegal, 1985

My definition of queerness goes beyond gender and sexuality. Queer is about how we perceive and position ourselves in relation to hegemonies. In this sense, Smith queered space. He played with the borders and loosened the boundaries. He created opportunities for origin, class, and expectation to be transgressed. In doing so he opened up new space for people to come together.

Collaboration is what happens when we arrive in space with others. It’s the process through which many new things become possible and imaginable. For me, it’s an important reason why we cross borders in the first place. It’s a purpose for why we gather and a reason why coming together and finding solidarity can be so uplifting in difficult times.

Willi Smith collaborated frequently, relying on partnerships with artists, photographers, theater and dance companies, film teams, and designers in other fields to amplify his ideas. A notable collaboration for me was WilliWear’s commission from the artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude to design the uniforms for security and welcome staff at their renowned Pont-Neuf Wrapped (1985) installation. Smith’s uniforms created a sense of task and authority, and simultaneously disrupted expectations of what security and authority might look like. Where one might expect an official seal or authoritative text, Smith placed a screenprint of a Pont Neuf drawing. Where one might expect a utilitarian, militaristic silhouette, Smith’s uniforms were loose to the point of requiring each wearer to deal with the excess fabric by individually styling their look. In this way, the uniforms echoed the Pont Neuf installation itself. How we clothe structures of authority changes how we understand the power and future of those structures.

![Linda Mason and Willi Smith on Set, Expedition, Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring 1986 Collection, Photographed by Mark Bozek, Dakar, Senegal, 1985]()

Linda Mason and Willi Smith on Set, Expedition, Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring 1986 Collection, Photographed by Mark Bozek, Dakar, Senegal, 1985

Collaboration is what happens when we arrive in space with others. It’s the process through which many new things become possible and imaginable. For me, it’s an important reason why we cross borders in the first place. It’s a purpose for why we gather and a reason why coming together and finding solidarity can be so uplifting in difficult times.

Willi Smith collaborated frequently, relying on partnerships with artists, photographers, theater and dance companies, film teams, and designers in other fields to amplify his ideas. A notable collaboration for me was WilliWear’s commission from the artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude to design the uniforms for security and welcome staff at their renowned Pont-Neuf Wrapped (1985) installation. Smith’s uniforms created a sense of task and authority, and simultaneously disrupted expectations of what security and authority might look like. Where one might expect an official seal or authoritative text, Smith placed a screenprint of a Pont Neuf drawing. Where one might expect a utilitarian, militaristic silhouette, Smith’s uniforms were loose to the point of requiring each wearer to deal with the excess fabric by individually styling their look. In this way, the uniforms echoed the Pont Neuf installation itself. How we clothe structures of authority changes how we understand the power and future of those structures.

Linda Mason and Willi Smith on Set, Expedition, Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring 1986 Collection, Photographed by Mark Bozek, Dakar, Senegal, 1985

A friend recently described to me the feeling of wearing a piece of WilliWear in their collection. They confessed that the clothes still feel empowering to wear, that they create a sense of character and confidence. Imbued with Smith’s legacy, the clothes have accumulated, rather than lost, power and relevance. In our difficult political time, the transformations of perception and embodiment that Smith’s works create remain a striking point by which we might reorient ourselves toward more open, queer, and collaborative futures.

Willi Smith died at thirty-nine, the same age I am now. How might the present look had there been more future for Smith? And how might we continue to disrupt and empower, to teach and poke fun? How might the style continue to facilitate crossings? These questions should face us not with regret, but with task. What futures can we continue to imagine? What futures can we enact in our work and in how we face the world? What futures can we embody?

Brendan Fernandes is an internationally recognized Canadian artist working at the intersection of dance and visual arts. His projects address issues of race, queer culture, migration, protest, and other forms of collective movement, and have been shown at the Guggenheim Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, the Getty Museum, and the National Gallery of Canada.

Willi Smith died at thirty-nine, the same age I am now. How might the present look had there been more future for Smith? And how might we continue to disrupt and empower, to teach and poke fun? How might the style continue to facilitate crossings? These questions should face us not with regret, but with task. What futures can we continue to imagine? What futures can we enact in our work and in how we face the world? What futures can we embody?

Brendan Fernandes is an internationally recognized Canadian artist working at the intersection of dance and visual arts. His projects address issues of race, queer culture, migration, protest, and other forms of collective movement, and have been shown at the Guggenheim Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, the Getty Museum, and the National Gallery of Canada.

- Eleanor Lambert Collection, Willi Smith Biography Coty “Winnie” Nominee 1978, 1978, 214.3.111, Fashion Institute of Technology|SUNY, FIT Library Special Collections and College Archives, New York, NY.

- “The Bright World of Willi Smith 1948–1987,” Women’s Wear Daily (April 20, 1987): 10.