Jeffrey Banks

I started my business in 1976 when I was twenty-two, the same year as Willi. I loved fashion during this time. There was me, there was Willi, there was Scott Barrie, there was Stephen Burrows, and there was Jon Haggins. It was lovely not to be the only Black designer on Seventh Avenue. As a child, I remember telling my former nursery school teacher, who was Black, when I was ten years old that I wanted to be a designer like Yves Saint Laurent. She responded, “Who has ever heard of a Black designer? That’ll never happen.” I was so angry, because my parents always raised me to believe that I could do and become anything I wanted as long as I worked hard for it.

Willi was not one of these designers who created in a vacuum. He loved art and the people on the street. He designed based on what someone really needed to go to work in, to play in, and to have fun in. He’d create a romper that would be worn at the beach and then a jacket to throw over the romper so that it could be worn in the office. The sixties were filled with short clothes and the freedom of stretch and pantyhose, throwing away the girdle, but the seventies launched the first real breakthrough in modern women’s clothes in America. The seventies were a time when women didn’t feel that if they went out to lunch, they had to wear a little suit by a designer with gloves, a hat, and a purse. They were wearing jackets over turtlenecks and jeans, and that had never happened before. In fact, a lot of restaurants in New York before the seventies wouldn’t allow a woman to come in wearing pants. The seventies were a big time for freedom, and Willi helped create that.

Willi was not one of these designers who created in a vacuum. He loved art and the people on the street. He designed based on what someone really needed to go to work in, to play in, and to have fun in. He’d create a romper that would be worn at the beach and then a jacket to throw over the romper so that it could be worn in the office. The sixties were filled with short clothes and the freedom of stretch and pantyhose, throwing away the girdle, but the seventies launched the first real breakthrough in modern women’s clothes in America. The seventies were a time when women didn’t feel that if they went out to lunch, they had to wear a little suit by a designer with gloves, a hat, and a purse. They were wearing jackets over turtlenecks and jeans, and that had never happened before. In fact, a lot of restaurants in New York before the seventies wouldn’t allow a woman to come in wearing pants. The seventies were a big time for freedom, and Willi helped create that.

Willi was the second big-name designer who passed away from AIDS, a little less than a year after Perry Ellis, who was also my good friend. This is in the context of the hysteria that was prevalent during the early eighties, when AIDS was first discovered. Laurie Mallet had a really difficult time after Willi died. A big part of it had nothing to do with the designs; it was the stigma of AIDS. People were so stupid that they thought if they wore clothes from a designer who had AIDS, they might somehow catch the disease. That’s how scary the times were and how much misunderstanding persisted.

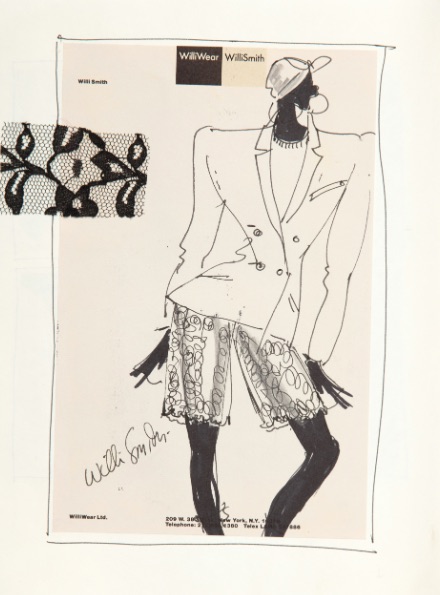

Cotton Club Gala Costume Design, Willi Smith, 1985