Patterns for You

Darnell-Jamal Lisby and Luiza Repsold França

This Willi Smith for Butterick Patterns 3254, 3245,

and 3246, 1973, catalogue editorial presents several

of the first patterns that Smith designed, including a menswear pattern that Smith is modeling in the

photo. These designs echo Smith’s fall 1973 collection for Digits, which was inspired by Christian Dior’s

influential spring 1947 “Corolle” line. This haute

couture collection was coined the “New Look” byHarper’s Bazaar editor-in-chief Carmel Snow for

reintroducing feminine cinched-waist silhouettes

after seasons of somber wartime fashion.

As the popularity of home sewing grew in the sixties

and seventies, commercial sewing pattern companies expanded their advertising budgets and invested in alternative promotional techniques, including recruiting celebrity spokespeople and models to promote their patterns. Pattern companies evolved their garment categories to include African-inspired designs, such as the dashiki, and began actively engaging with African American models and designers.1

Willi Smith began designing patterns for Butterick in 1973 while he was still the creative mind behind the sportswear label Digits.2 His first collection published in Butterick’s catalogue during the spring of 1973 featured six patterns, including one menswear design that was meant to be replicated in wool for the fall.3 The collection was also publicized through the July issue of Mademoiselle magazine, a promotional partnership with the Wool Bureau and eight textile mills, as well as through a traveling fashion show featuring variations of each style.4 When Smith designed for Butterick from 1973 to 1981, his patterns were featured alongside the likes of Betsey Johnson and Kenzo in the Young Designers section of each issue. In 1982 when Smith partnered with McCall’s Pattern Company, his designs were extremely similar to his WilliWear collections, comprising billowing, layered pieces for consumers to reproduce. McCall’s integrated the patterns that Smith and his fellow designers created throughout its issues in various sections of the catalogue, further democratizing the designers’ patterns within the company.

In a 1979 interview with On-Ke Wilde for Women’s Wear Daily, Smith said, “There are also a lot of men who sew these days, and I don’t just mean designers,” prefacing how attuned he was to the growing number of male home sewers who used his patterns made for a predominantly female audience.5 Supporting Smith’s claim, Wilde included a brief quote from the design director of Butterick, Diane Vega, adding, “I know that there are men who have used Willi’s patterns for themselves; some of his designs can be used for both sexes.”6 Following the introduction of the first WilliWear menswear collection in 1983, Smith began creating patterns with explicitly gender-fluid designs, a concept already practiced in his runway shows and presentations. Smith’s patterns usually included tailored shirts, blazers, and pants in his characteristic mix of cultural and fashion-historical references, and featured illustrations with male and female figures wearing the same garments.

and seventies, commercial sewing pattern companies expanded their advertising budgets and invested in alternative promotional techniques, including recruiting celebrity spokespeople and models to promote their patterns. Pattern companies evolved their garment categories to include African-inspired designs, such as the dashiki, and began actively engaging with African American models and designers.1

Willi Smith began designing patterns for Butterick in 1973 while he was still the creative mind behind the sportswear label Digits.2 His first collection published in Butterick’s catalogue during the spring of 1973 featured six patterns, including one menswear design that was meant to be replicated in wool for the fall.3 The collection was also publicized through the July issue of Mademoiselle magazine, a promotional partnership with the Wool Bureau and eight textile mills, as well as through a traveling fashion show featuring variations of each style.4 When Smith designed for Butterick from 1973 to 1981, his patterns were featured alongside the likes of Betsey Johnson and Kenzo in the Young Designers section of each issue. In 1982 when Smith partnered with McCall’s Pattern Company, his designs were extremely similar to his WilliWear collections, comprising billowing, layered pieces for consumers to reproduce. McCall’s integrated the patterns that Smith and his fellow designers created throughout its issues in various sections of the catalogue, further democratizing the designers’ patterns within the company.

In a 1979 interview with On-Ke Wilde for Women’s Wear Daily, Smith said, “There are also a lot of men who sew these days, and I don’t just mean designers,” prefacing how attuned he was to the growing number of male home sewers who used his patterns made for a predominantly female audience.5 Supporting Smith’s claim, Wilde included a brief quote from the design director of Butterick, Diane Vega, adding, “I know that there are men who have used Willi’s patterns for themselves; some of his designs can be used for both sexes.”6 Following the introduction of the first WilliWear menswear collection in 1983, Smith began creating patterns with explicitly gender-fluid designs, a concept already practiced in his runway shows and presentations. Smith’s patterns usually included tailored shirts, blazers, and pants in his characteristic mix of cultural and fashion-historical references, and featured illustrations with male and female figures wearing the same garments.

Smith did not see his sewing patterns for Butterick

and McCall’s as competing with his ready-to-wear collections; rather, he found that the two markets complemented each other.7 Pattern designs were selected and adapted from the previous season’s collection of his ready-to-wear line, fulfilling his desire to expand his brand while also making his clothing even more affordable and accessible.8

Smith respected the home sewers’ awareness of their bodies and willingness to take risks, and saw this audience as more intimately connected to fashion as a means of individual expression than the ready-to-wear shoppers who followed the colors and trends of the runway.9 He understood how choosing the pattern, selecting a custom fabric, and assembling the full garment allowed many possibilities for invention. A dynamic design for a top, for example, allowed sewers to create a blouse, a tunic, and a dress all from a single base pattern.10 Smith, an inherently collaborative spirit, was driven by how pattern design allowed him to share the design process with his consumers.

Luiza Repsold França supported Willi Smith: Street Couture as a Peter A. Krueger Intern at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Originally from Rio de Janeiro, she is a senior at the University of Pennsylvania pursuing a B.A. in the history of art and minoring in fine art and English with a focus on Latinx culture and the intersection of craft and fine art.

Darnell-Jamal Lisby is a fashion historian and project curatorial assistant at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. His contributions to various publications and curatorial efforts explore the art historical context surrounding Blackness and the history of fashion.

and McCall’s as competing with his ready-to-wear collections; rather, he found that the two markets complemented each other.7 Pattern designs were selected and adapted from the previous season’s collection of his ready-to-wear line, fulfilling his desire to expand his brand while also making his clothing even more affordable and accessible.8

Smith respected the home sewers’ awareness of their bodies and willingness to take risks, and saw this audience as more intimately connected to fashion as a means of individual expression than the ready-to-wear shoppers who followed the colors and trends of the runway.9 He understood how choosing the pattern, selecting a custom fabric, and assembling the full garment allowed many possibilities for invention. A dynamic design for a top, for example, allowed sewers to create a blouse, a tunic, and a dress all from a single base pattern.10 Smith, an inherently collaborative spirit, was driven by how pattern design allowed him to share the design process with his consumers.

Luiza Repsold França supported Willi Smith: Street Couture as a Peter A. Krueger Intern at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Originally from Rio de Janeiro, she is a senior at the University of Pennsylvania pursuing a B.A. in the history of art and minoring in fine art and English with a focus on Latinx culture and the intersection of craft and fine art.

Darnell-Jamal Lisby is a fashion historian and project curatorial assistant at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. His contributions to various publications and curatorial efforts explore the art historical context surrounding Blackness and the history of fashion.

- Joy Spanabel Emery, A History of the Paper Pattern Industry: The Home Dressmaking Fashion Revolution (New York: Bloomsbury, 2014), 188–92.

- “Butterick Introducing Willi Smith, ‘Digits’ Collection in the September-dated Catalog,” Fabric News (April 1973).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- On-Ke Wilde, “Counter-Points,” Women’s Wear Daily 138, no. 117 (June 19, 1979): 30.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Willi Smith for Butterick Pattern 3254 from 1973 introduces a menswear set that interprets the Norfolk jacket, a staple of men’s sportswear in England during the second half of the nineteenth century often adapted for military and law-enforcement uniforms. This pattern illustrate an early example of Smith’s interest in uniform dress, a reference he adapted frequently throughout his career.

Willi Smith for Butterick Pattern 5046 from 1976 illustrates Smith’s love affair with the jumpsuit, a garment with origins in both the artistic community and dress history. H. D. Lee Mercantile Company (which later became known for Lee jeans) introduced the Lee Union-All one-piece coverall in 1913, worn predominately by blue-collar workers, while futurist artist Thayaht (pseudonym of Ernesto Michahelles) is credited with introducing the jumpsuit into civilian closets in 1919 after being inspired by parachute jumpers.

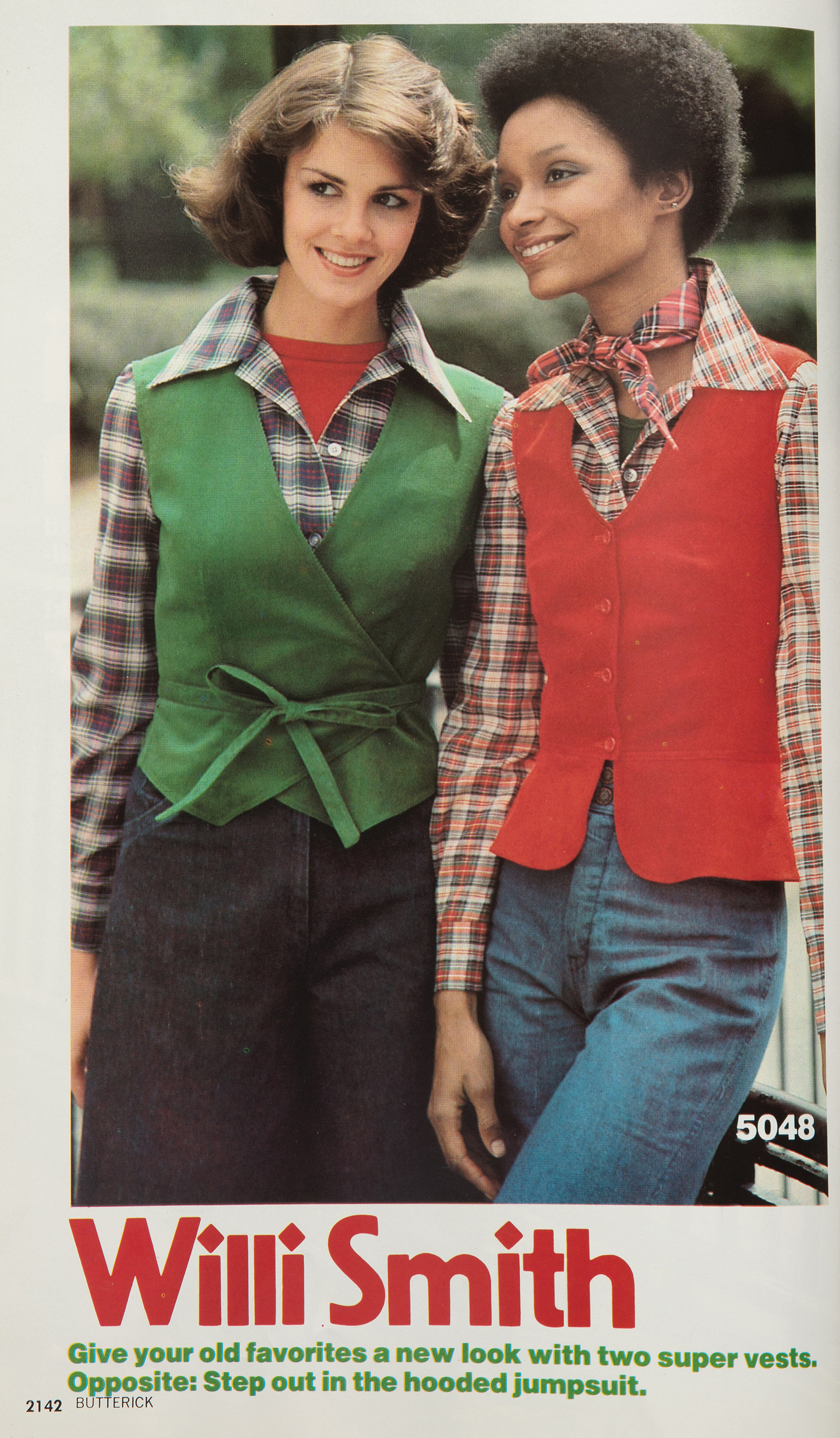

Willi Smith for Butterick Pattern 5048 from 1976 emphasizes voluminous sleeves and a streamlined vest reminiscent of womenswear in the thirties and forties, decades Smith pulled from in collections for Digits and eventually WilliWear. These patterns are shown in a tartan wool twill and styled with a complementary bandana, revealing Smith’s interest in dress associated with nostalgic imagery of the American West.

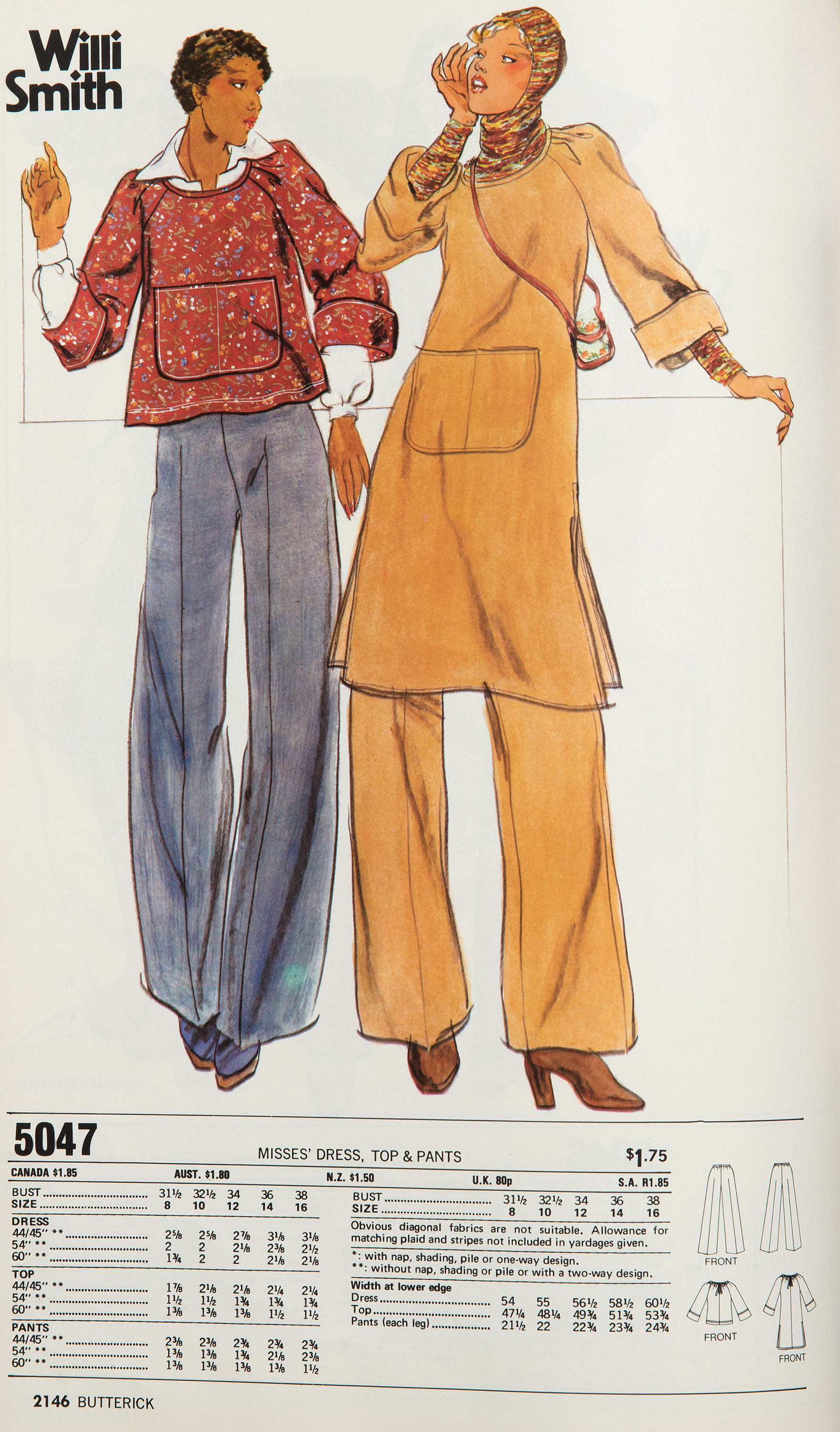

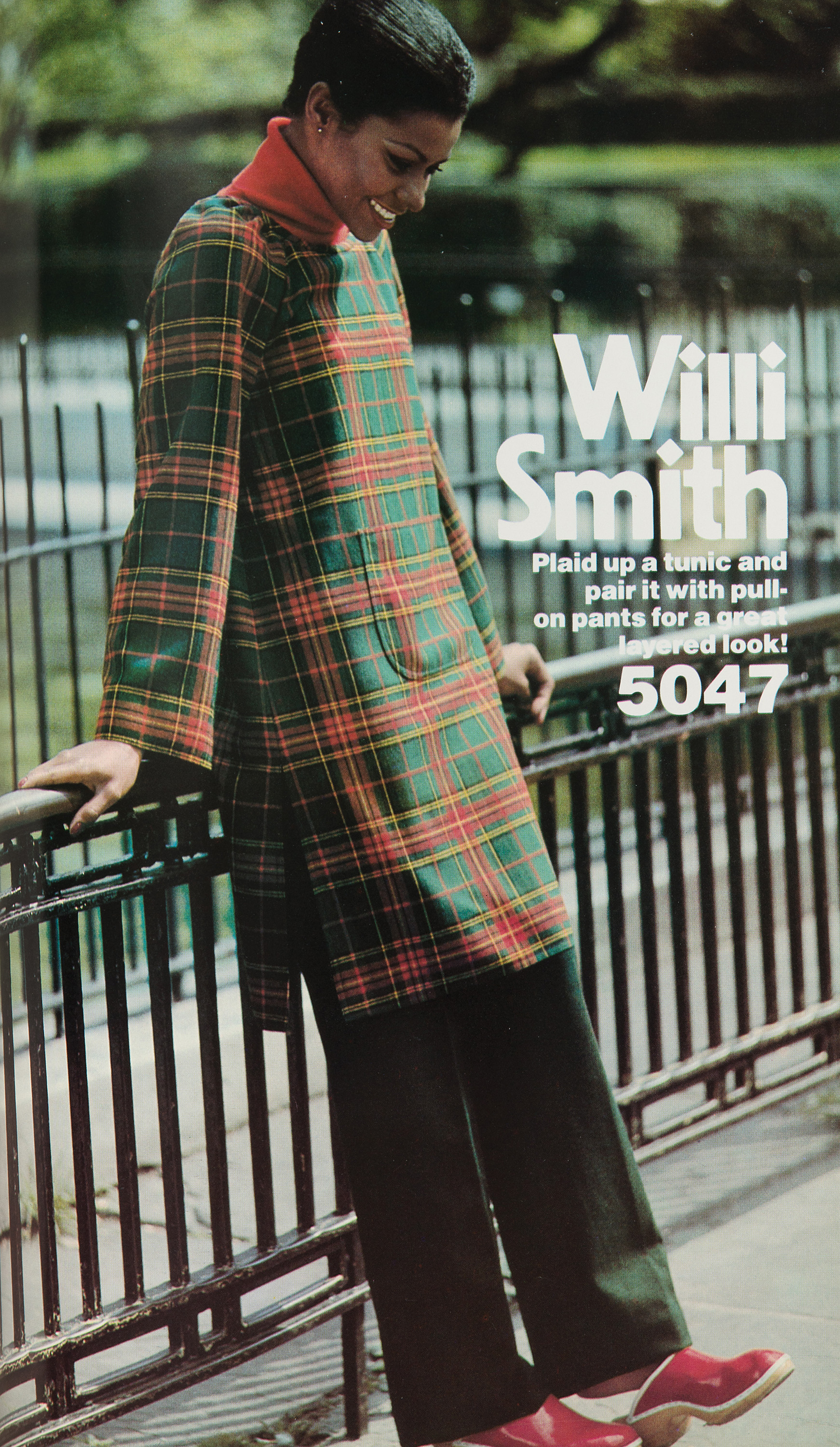

Willi Smith for Butterick Pattern 5047 from 1976 marries two of Smith’s major creative inspirations: dress native to communities in South and Central Asia, depicted here as a version of the salwar kameez, a tunic and trouser ensemble worn by people of all classes, and uniform dress, referenced here in a generous apron pocket. Smith frequently designed garments that could transition from domestic to public spaces, and this particular expression reveals his experimentation with combining multi- cultural democratic garments to create a new adaptive wardrobe.

Willi Smith for McCall’s Pattern 6475 from 1979 emulates Smith’s WilliWear fall 1978 “musketeer”-inspired collection, which feminized traditional masculine ensembles through layered blouses cinched with cummerbunds under fitted vests with tapered bodies and padded shoulders. Like the collection, these patterns are a romantic reinterpretation of seventeenth-century men’s and women’s styles.

Willi Smith for McCall’s Pattern 6475 from 1979 emulates Smith’s WilliWear fall 1978 “musketeer”-inspired collection, which feminized traditional masculine ensembles through layered blouses cinched with cummerbunds under fitted vests with tapered bodies and padded shoulders. Like the collection, these patterns are a romantic reinterpretation of seventeenth-century men’s and women’s styles. WilliWear for McCall’s Pattern 7947 from 1982 suggests a slight leg-of-mutton sleeve, which pays homage to the development of ready-to-wear womenswear in the 1890s by way of the shirtwaist, a button-down blouse made for the evolving active lifestyles of women during this period. The voluminous, fashionable silhouette at this time was modeled after the athletic “Gibson Girl” archetype that utilized the leg-of-mutton sleeves as a way to visually broaden a woman’s shoulders.

WilliWear for McCall’s Pattern 7947 from 1982 suggests a slight leg-of-mutton sleeve, which pays homage to the development of ready-to-wear womenswear in the 1890s by way of the shirtwaist, a button-down blouse made for the evolving active lifestyles of women during this period. The voluminous, fashionable silhouette at this time was modeled after the athletic “Gibson Girl” archetype that utilized the leg-of-mutton sleeves as a way to visually broaden a woman’s shoulders.

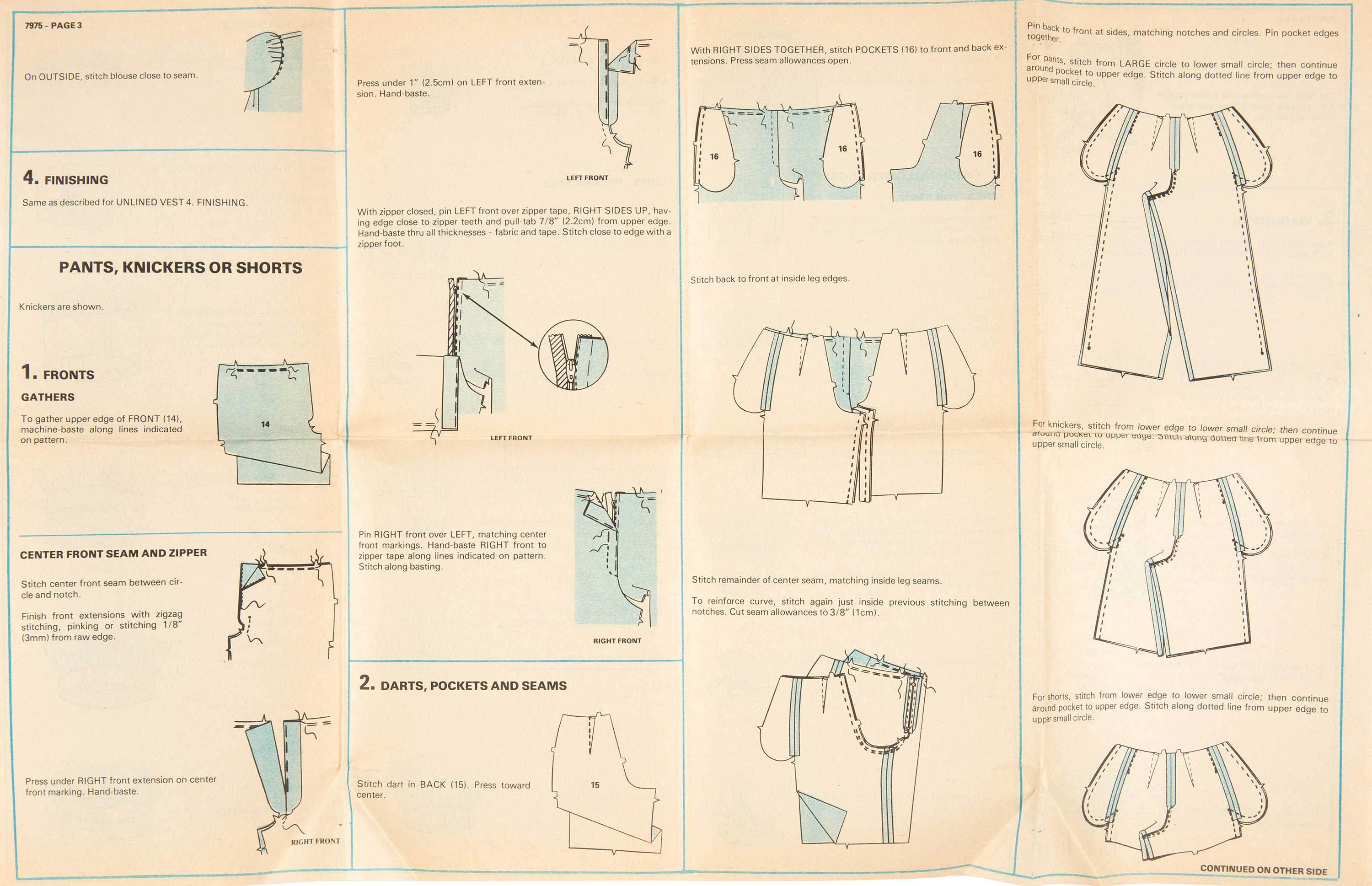

WilliWear for McCall’s Pattern 7975 from 1982 evokes late nineteenth century bloomers, championed by women’s rights activist Amelia Bloomer as a liberating alternative to petticoats. Smith’s cheeky play on dynamic underwear as outerwear was previously employed in his spring 1982 WilliWear collection and plastered in his Art as Damaged Goods installation at P.S. 1 that same year.

WilliWear for McCall’s Pattern 8703 from 1983 melds coveralls with Western accessories for women. The image of U.S. women in coveralls became iconic during World War II when women temporarily transitioned into blue-collar jobs traditionally held by men. Westinghouse Electric’s popular depiction of “Rosie the Riveter” has become a familiar symbol of female empowerment. Vests were commonly worn by men during the height of migration to the West during the nineteenth century, but the vests that cowboys wore consisted of durable materials such as animal hide to minimize snagging on foliage. Vests also provided easy access to small objects cowboys couldn’t store in their pants while they were riding. Smith’s introduction of the vest over the coverall creates a strong amalgamation of historically masculine utility clothing, styled for women.

WilliWear for McCall’s Pattern 8535 from 1984 encourages sewers to use natural fibers such as linen and cotton to render the long jacket, trousers, and shorts. Seen in Smith’s 1985 film Expedition, this safari suit reboot alludes to Smith’s awareness of colonialism and frequent integration of elements associated with the history of colonial dress in West Africa and Southeast Asia.

WilliWear for McCall’s Pattern 8535 from 1984 encourages sewers to use natural fibers such as linen and cotton to render the long jacket, trousers, and shorts. Seen in Smith’s 1985 film Expedition, this safari suit reboot alludes to Smith’s awareness of colonialism and frequent integration of elements associated with the history of colonial dress in West Africa and Southeast Asia.

WilliWear for McCall’s Pattern 3033 from 1984, highlights Smith’s frequent use of gingham, which has histories of use in Japan, India, and Africa. Gingham, a plain-woven textile, typically cotton, with a checked colored pattern, was a major export of mills in Manchester, England, during the eighteenth century due to its inexpensive and reversible composition, and has been produced in the United States for centuries. The decision to illustrate these familiar WilliWear basics in gingham alludes to Smith’s attraction to affordable utilitarian fabrics, uniform dress, and the tartan wool designs worn in the American West.

WilliWear for McCall’s Pattern 9637 from 1985 presents Smith’s continued play with gender norms for general public consumption. Floral prints in menswear date back to eighteenth-century men’s banyans and eventually coats, but they fell out of favor as the nineteenth century progressed, as that level of ostentation was seen as too frivolous and feminine. The use of this print celebrates the reintroduction of bold floral prints for men in the sixties and the normalizing of gender-neutral style in the seventies in the United States at a time when gender norms were being reintroduced into mainstream fashion.

WilliWear for McCall’s Pattern 9637 from 1985 presents Smith’s continued play with gender norms for general public consumption. Floral prints in menswear date back to eighteenth-century men’s banyans and eventually coats, but they fell out of favor as the nineteenth century progressed, as that level of ostentation was seen as too frivolous and feminine. The use of this print celebrates the reintroduction of bold floral prints for men in the sixties and the normalizing of gender-neutral style in the seventies in the United States at a time when gender norms were being reintroduced into mainstream fashion.

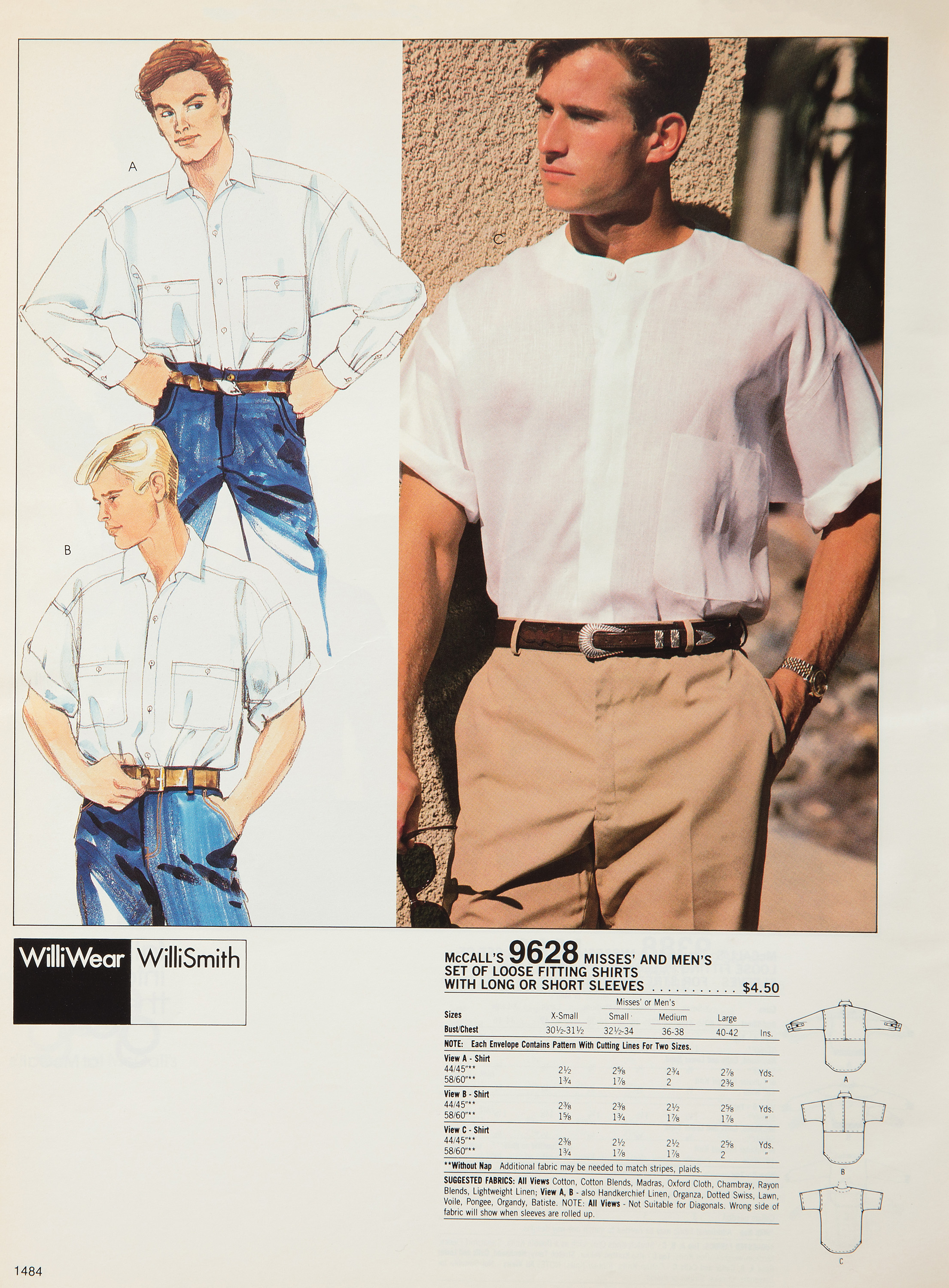

WilliWear for McCall’s Pattern 9628 from 1985 points to typical Smith fusion, combining dress associated with Southeast Asian communities with American Western wear and military dress. The slight standing collar of the shirt pattern represents a mixture of the kurta tunic and the Nehru jacket, a style associated with the uniform of Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India; it was originally derived from the silhouette of the jackets worn by Chinese mandarins, government officials during the Qing dynasty. Smith’s pattern for the shirt is paired with blue jeans and khaki pants with a thin belt, accessorized in the editorial photograph as a Barry Kieselstein-Cord design that Smith was often photographed wearing.

WilliWear for McCall’s Pattern 9628 from 1985 points to typical Smith fusion, combining dress associated with Southeast Asian communities with American Western wear and military dress. The slight standing collar of the shirt pattern represents a mixture of the kurta tunic and the Nehru jacket, a style associated with the uniform of Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India; it was originally derived from the silhouette of the jackets worn by Chinese mandarins, government officials during the Qing dynasty. Smith’s pattern for the shirt is paired with blue jeans and khaki pants with a thin belt, accessorized in the editorial photograph as a Barry Kieselstein-Cord design that Smith was often photographed wearing.