Polydisciplinary

Magnetism

Judith Barry, Prem Krishnamurthy, and Forest Young

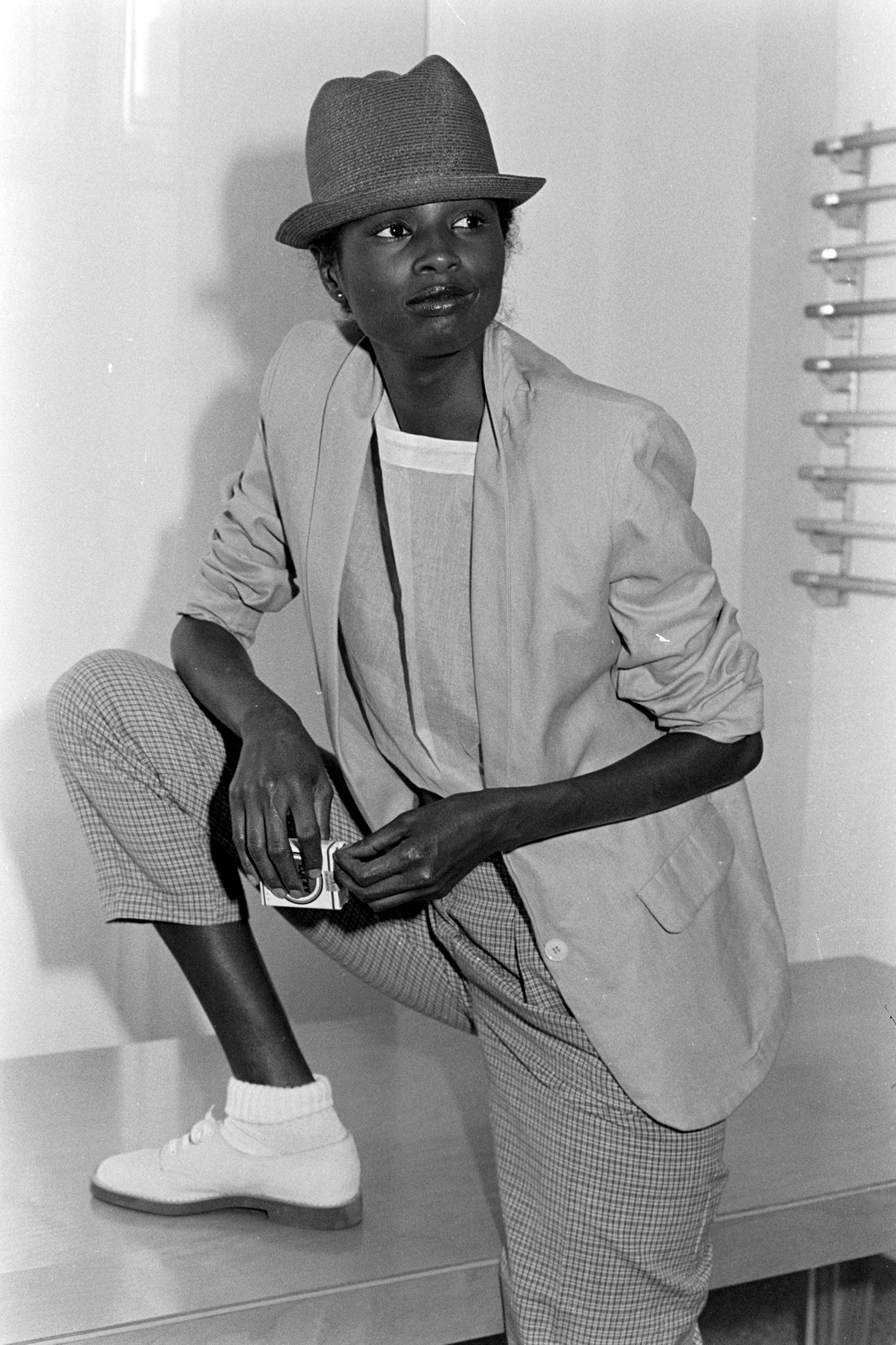

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Resort 1979 Collection, 1978

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Resort 1979 Collection, 1978Prem Krishnamurthy:

Judith Barry:

I am a relative newcomer to Willi Smith; I was first introduced to his work through James Wines and the designs that SITE created for WilliWear in the eighties. As a model, WilliWear brings up important questions around the politics of distribution. The brand stood for accessibility and affordability—essential parts of the modern project, as in canonical examples like Jan Tschichold’s design for Penguin Books—and demonstrated that mass production and broad appeal can go hand-in-hand with aesthetic quality. This approach to distribution is an ideological position in itself. At the same time, Willi Smith pioneered the idea of collaborating with artists and creative practitioners from other fields, in ways that still seem fresh today.

When Alexandra [Cunningham Cameron] asked me to help convene this conversation, it seemed like a perfect opportunity to touch on these topics and others in dialogue with practitioners who have a longer exposure to and understanding of WilliWear. In her critical artistic work since the eighties, Judith Barry has consistently explored the consumer gaze, the politics of display, and the productive frictions between design and art. Forest Young brings extensive experience working within branding on a global level, while also collaborating with artists such as Titus Kaphar on critical, socially oriented projects that incorporate design. Both of them have known Willi Smith’s work for a long time and bring their perspectives to bear on it.

I’m so glad that you both could join and am excited to hear your thoughts.

Judith Barry:

I didn’t personally know Willi Smith, although I did know the clothes, and he lived across the street from the editor of the Architect’s Newspaper, William Menking. Several friends wore and collected his clothes, including Lynne Tillman. My interest in his work was based on the performativity of his fashion in particular, and its functionality, and that it appealed to everyone. I codesigned two shows that considered fashion as a performative collaborative activity: [Impresario] Malcolm McLaren and the British New Wave at the New Museum in 1988 with Ken Saylor and a retrospective on Geoffrey Beene in 1994 at the Fashion Institute of Technology with J. Abbott Miller. Both used the exhibition space as a way to make visible how fashion constructs ways in which to inhabit physical space while simultaneously embodying the people wearing the clothes. Willi Smith’s clothing does that as well.

For me, thinking about Willi Smith is also an invitation to think about the place of fashion in our contemporary culture. And that raises all kinds of questions about the body in clothes, the function of the muse in fashion, and the exchange between the wearer of the clothing and the physicality of space itself as a boundary condition. Contemporary films like Phantom Thread address this somewhat, and even though I found that film problematic, I did see it as an attempt to situate fashion within the realm of psychoanalysis, alluding to moments where fashion as fetish takes on a life of its own, recalling the nineteenth-century stories of Guy de Maupassant; whereas Willi Smith’s clothing was active, putting the body into motion, and figuratively provoking dance.

Forest Young:

It’s interesting to situate Willi Smith within a specific continuum of fashion. Street Couture is his emblematic celebration of the “street” as a source of inspiration, echoing Prem’s concise focus into the democratization of fashion and the designer’s famous remark of designing for the royal passersby and not the queen herself.

As Virgil Abloh’s Figures of Speech show is finishing its run at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, there is a chain of influence that we could collectively imagine—from Charles James to Arthur McGee to Smith, to a contemporary polymath like Abloh. We first observe visionary craft, then a context shift of influence from the runway to the street to a final blurring of disciplinary lines altogether. We can deduce by wearing WilliWear clothes and engaging in conversations like these that freedom of movement, literally and metaphorically, was a distinguishing center of gravity for his work. It is a mature take on democratization, both in terms of price point but also an ethos with integrity. The point that Judith raises about the body and his focus on comfort and a completely nonironic fascination with fit and mass appeal prefigures the trend of democratization we will see with Halston and later Isaac Mizrahi, not as a diffusion line, but as the brand itself. Willi Smith had an undeniable polydisciplinary magnetism. But his prescient reframe of accessibility is worth noting.

JB:

Yes, I totally agree. The comfort in his clothing is important because you could actually transform yourself in his clothing from the day to the night. I had friends who wore his clothing to go to work at jobs where you had to dress a certain way, but then would go out at night dancing because you could really twirl in his clothes. I remember friends in his long skirts especially, and they would be whirling around in them. It was a happy moment of transformation. He seems to have made a very conscious decision to make his clothes appealing for women, giving them a certain kind of power with his suits and wide shoulders while still being feminine. You could dress well without having to spend a huge amount of money. That was extremely important to him.PK:

Judith, your work in the eighties—I’m thinking of Casual Shopper in particular—thought deeply about the state of consumer culture during that particular moment. Your comment about conflating the daytime with the nighttime is quite interesting because it speaks to movements in between so-called work and so-called life. In your experience, how were those binaries set up in the eighties era?

JB:

For Casual Shopper, I was thinking about the question of desire and how desire and fantasy circulate within fashion and are further evoked in the activity of shopping. When I first came to New York as a student, in the late seventies, New York was really inexpensive. The downtown art world was tiny— Andy Warhol, the Velvet Underground, Jonas Mekas, performance, conceptual, and minimal art, and most galleries were in SoHo. And punk culture existed alongside this as well. There was a huge divide between “high art” and “popular culture.” Gradually over the eighties this divide started to meld together. During the seventies, most clubs were punk like CBGB, the Red Bar, the Mudd Club et al. Then in the eighties, with Studio 54 for dancing, the Pyramid Club for staging performance and reoccurring soap operas, and Nell’s which was a louche supper club, the demographic became much more mixed.

There were also other dramatic changes. In just ten years, rents ballooned from forty to four hundred dollars. Meanwhile, in 1977, Douglas Crimp’s Pictures exhibition was at Artists Space. This effectively launched postmodernity and signaled the embrace of the art market, and a very different relationship between art and popular culture. Artists rented storefronts in the East Village showing their colleagues’ work, and suddenly artists were dealers. Postmodernity was a unifying discourse despite its analytical approach and included feminisms of many different stripes, as well as psychoanalysis, semiotics, post-structualism, film, and literary and political theory. Also, the art world expanded to allow subject matter that previously was not considered part of the art discourse, such as fashion. I always wondered if fashion designers were reading Laura Mulvey’s article “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”? Many seemed to have as sophisticated a relation to questions about the place of women in culture as artists had.

Willi straddled that period: from the seventies—a gritty New York with punk clubs—into the glamourous eighties—Studio 54, AREA, Palladium, Danceteria, and many others. Artists were perceived as glamorous as well, and each day brought invitations to club parties—artists were invited gratis as lures, as window dressing, and we were all transforming alongside all of this as well. Willi, I think, was very aware of this, and his clothes reflected the fun of this as well as the reality of what was happening, and the possibilities.

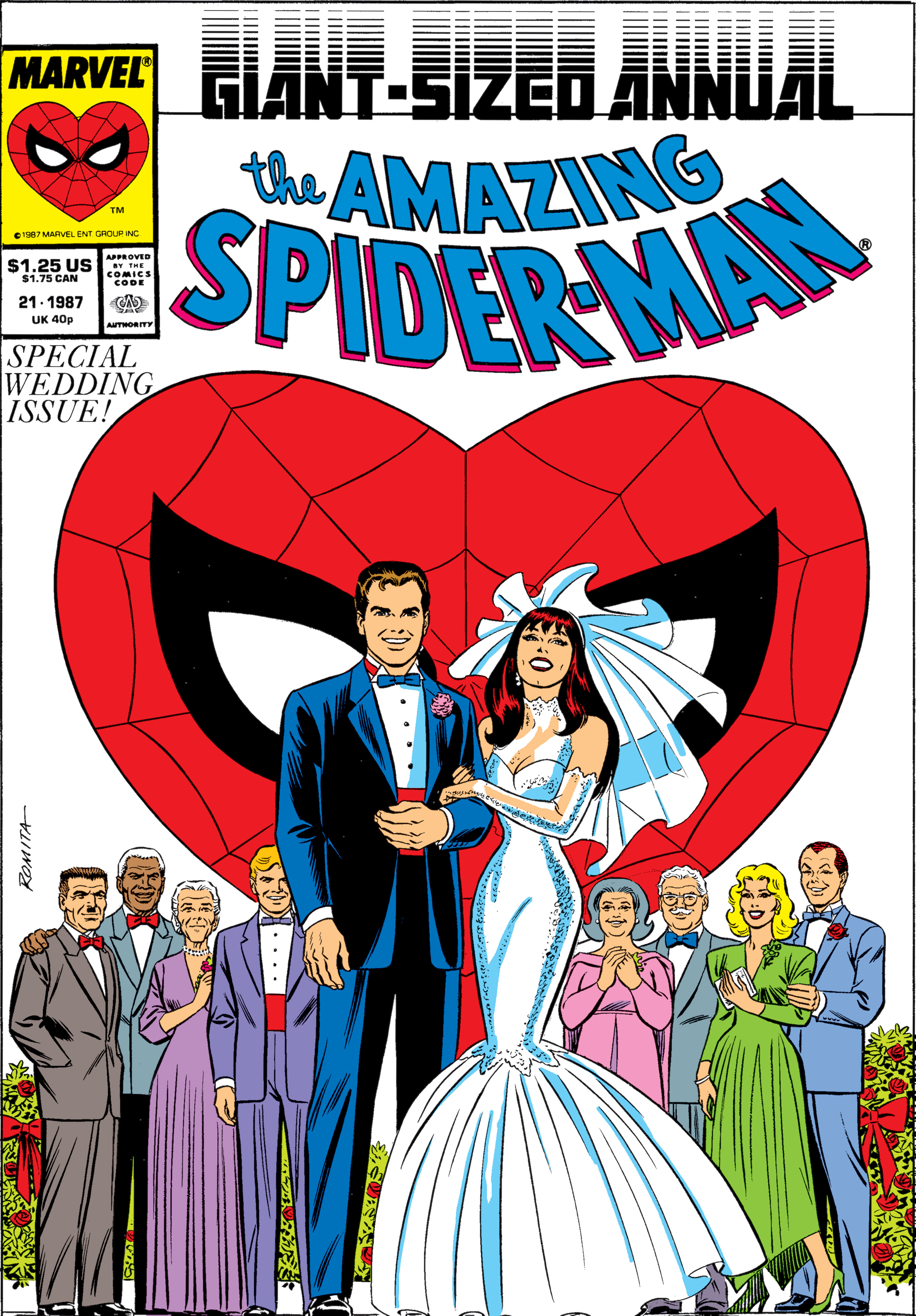

Willi Smith for Marvel, Mary Jane Wedding Dress,

Amazing Spider-Man Annual, 1987

Willi Smith for Marvel, Mary Jane Wedding Dress,

Amazing Spider-Man Annual, 1987

Willi’s adherence to accessibility as a creative constraint is remarkable. It can’t be limited by the simple boundaries of affordability and human factors; it is also about tapping into a cultural fabric, a pulse.

PK:

FY:

This image sets the stage for considering the interaction between the art world and the fashion world. Forest, I’m curious about something you mentioned. On the one hand, Willi Smith represents the example of a fashion entrepreneur who emphasizes the affordability of his clothes. He even makes patterns available for his designs. He wants people to be able to buy them. At the same time, he’s working with the art world’s prominent players on a high level. Do you see this as a contradiction?

FY:

This is really interesting—expansive influence via collaboration. We could conjure Ruth E. Carter’s early work for School Daze; Willi’s focus on the theatrical experience with Bill T. Jones, Arnie Zane, and Keith Haring; and his posthumously realized design for Mary Jane’s wedding dress for the Spider-Man wedding at Shea Stadium—forever preserved in The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #21. The latter, one of Marvel’s greatest promotions of all times, nods to the superhero zeitgeist decades away, and Carter’s monumental follow-up in Black Panther.

The point: there is nothing more accessible than comic books as an approachable, time-based experience; the comic book cells in #21 speak to how Willi is weaving in and out of culture at a very adept level. He is present as part of this design fiction that’s also happening in real life, which speaks to his ability to reconcile the transformative power of a cultural experience with affordability. Collapsing streetwear and high fashion is now commonplace and full-tilt Off-White and LVMH are proof of this. In contrast, Willi’s adherence to accessibility as a creative constraint is remarkable. It can’t be limited by the simple boundaries of affordability and human factors; it is also about tapping into a cultural fabric, a pulse.

JB:

Yes, comic books were read across class, race, and gender boundaries. But what he was doing was not something seen in fashion at the time. Willi collaborated with Barbara Kruger, Keith Haring, Nam June Paik, Juan Downey, and Miralda. He had a deep understanding of street culture, possibly through graffiti because graffiti art was a kind of diversity platform. It didn’t matter what color you were, and don’t forget it was all over New York City in the late seventies and mid-eighties. Many artists and designers were collaborating. Jenny Holzer and Lady Pink, Steven Sprouse and Keith Haring, and especially Fashion Moda in the South Bronx, directed by Stefan Eins, Joe Lewis, and William Stout, which had deep ties to the South Bronx neighborhood and which paved the way for the art world’s acceptance of graffiti art and the birth of DIY, especially in music such as hip hop.

Bill Bonnell for WilliWear, Invitation, Spring 1984 Presentation, 1983

Bill Bonnell for WilliWear, Invitation, Spring 1984 Presentation, 1983FY:

I’m going to piggyback on something, Judith, that I think is totally apropos, which is this relationship between cost and value. The cost of a spray can versus the perceived value of being able to canvas a subway car or a facade at a major intersection. In the eighties, whether owed to the emergence of hip hop or a particular distance from disco, way of expressing oneself with nothing other than your body, a piece of cardboard, or a spray can became commonplace. A Radio Raheen–esque boombox you save up all your money to have for the purposes of street envy. It becomes possible to manifest a complete, hyperlocal atmosphere.

While disco required the apparatus of a club, DJ, and bell-bottomed costuming, the eighties ushered in an era of ad hoc expression. The use of the body was essential to what was happening on the street and bled into artistic movements. Contemporary artists were using the body as the primary tool of making, like David Hammons’ body prints or hand-rolled “Bliz-aard” balls.

JB:

PK:

I agree and was trying to think of other artists from that period who were using their bodies—Faith Ringgold, Adrian Piper, and Lorraine O’Grady, of course. Certainly Jean-Michel Basquiat. Mel Edwards, Rafael Ferrer, and David Hammons, as Forest mentioned—although he was hard to find because he kept under the radar, but was often at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe run by Bob Holman. Martin Puryear was sometimes there. There was also a lot of poetry in the East Village after punk ended. Musicians and poets were often included on the same slam bills.

PK:

There is the inevitable question around race and Willi’s work. He did express concerns that the fashion industry often qualified his work through his race. I couldn’t help but notice in the WilliWear communications and graphics designed by people like Tibor Kalman and Bill Bonnell that there’s often a play with dichotomies of white and black, mirrored forms, or positive and negative compositions. I’m curious if that stood out to you, Forest.

M&Co. for WilliWear, Postcard, 1987

M&Co. for WilliWear, Postcard, 1987

FY:

JB:

Looking across the ecosystem of WilliWear artifacts through a graphic and typographic lens, there’s a considerable amount to discuss. Bill Bonnell brought equal parts graphic potency and textural sensitivity to the WilliWear expression.

Bonnell employs an unassuming, traditional cut of Futura for the WilliWear wordmark. The black-and-white squares that contain the letterforms echo a sixties op-art note, or earlier Japanese Nōtan, as the typography vibrates alongside a high-contrast motif. Over time we observe an element of play and whimsy embedded within those elongated twin Ls. The two Ls peek above the cap height at varying lengths, sometimes drawn to cap height, sometimes elongated further and even on rare occasions enclosing the entirety of the wordmark.

This dance of pragmatism and surprise was an essential ingredient of “radical modernism,” a phrase coined by Dan Friedman, who helped to facilitate the collaboration between both parties. The twin Ls echo contemporary brands like Billie, and a discernible return to sans serif expression across the realm of fashion. In retrospect, this identity is a lovely complement to Bonnell’s “In every child who is born . . .” poster from 1971 for the Container Corporation of America.

Bonnell is also unusually skilled in bringing texture to an otherwise 2D graphic scheme. From material choices, like the paper stock for the WilliWear business cards, hand-drawn elements alongside vibrant graphic fields, and compelling surface applications, the WilliWear graphic experience translates the materially rich environs created by SITE into takeaway ephemera.

JB:

That reminds me again of the question of design in fashion, and also that even in the eighties “design as design” occupied the position of “that which could not be named.” If you look at minimal art from a design perspective, you see how indebted that art movement is to industrial design. By the mid-nineties, and the ebbing of postmodernity, design could be openly discussed. When I designed Damaged Goods as my artist’s contribution to that exhibition at the New Museum in 1986, it was unusual to foreground exhibition design as an artist strategy. Early on, Willi posed the questions “What is design?” and “What is fashion?” in a very subtle, playful way. His installation at P.S. 1, Art as Damaged Goods, from 1982, is a good example of this.

Forest’s discussion about branding reminded me of T. J. Clark’s The Painting of Modern Life. Clark discusses shopgirls in the mid-nineteenth century as mutating into different people over the course of a day. First, arriving in Paris from rural areas and changing into shopgirl uniforms, then changing after work into bourgeois clothing where these girls are suddenly indistinguishable from their department store clientele, and later, perhaps donning an evening dress, perhaps shared among them, to go out with a male friend. Artists in the eighties often evoked similar strategies in their use of fashion and design codes to signify particular meanings. If you think about Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills in relationship to Édouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe or Olympia, you can see that all rely on a reading of very specific codes in order to produce their meanings. On a primary level this is their overt content, and on a secondary level these are the meaning associations conveyed more subtly through mise-en-scène, color, accessories, hair and makeup, and so on. I’m trying to argue that fashion design, at the level of the garment, and when it is successful, can conjure a sense of an inhabitable world that the wearer embodies. And certain fashion designers, such as Willi, produce this with an economy of means.

FY:

That’s a really good point. He legitimately pioneered what he called “street couture,” which I think is very interesting, Prem, to your point earlier about his prefiguring what we now see at LVMH and elsewhere. JB: In short, he possessed a deft understanding of street culture as the nexus point for innovation and collaboration. In practice, he managed to blend the graphic opulence of haute couture with the immediacy of the everyday. This, married to a high-margin supply chain with a bespoke component at the top. He reinserted the street within a historical legacy that merges all of the plastic arts, establishing fashion as one of the many vehicles affecting culture.

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring/Summer 1987

Presentation, 1986

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring/Summer 1987

Presentation, 1986 Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring/Summer 1987

Presentation, 1986

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring/Summer 1987

Presentation, 1986

JB:

PK:

FY:

PK:

That’s true. His silhouettes give a nod to French fashion post-World War II, such as Chanel and Dior, who emerged from austerity with drapery plus an abundance of fabric. But Willi found a way through the color, pattern, and affordability of his line to introduce choice and allow a variety of women to construct their own identities wearing his clothes differently. Many other designers of the eighties couldn’t quite pull off the eclectic exuberance of his clothing. He designed clothes that allowed for many possibilities.

Forest, you mentioned owning some Willi Smith clothes. How did you first encounter his work?

FY:

Shopping with the family. There was a ritual phenomenon that existed—the moment of discovering WilliWear had to be followed by a loud “Willi!” I’m imagining I was eight or nine years old. This was the eighties, and I was just totally smitten by the alliteration of the brand name. It’s an incredibly seductive thing to say over and over again and possibly in an annoying way. There was a subtly celebratory quality to this, both knowing the creator was a designer of color and that it was within a price point to be acquired immediately. The clothes were there to move in and have fun in an innocent, straightforward way. He was somehow able to exact fun in the form of an object. As an intentional commodity. I will wear my WilliWear coat to the opening of the exhibition if it’s still cold outside.

PK:

It makes me think about joy, too. One of the things that strikes me is that when we think about so-called collaborations between fashion and art today, the goal often seems to be to encourage aspirational thinking, to raise the value and potentially the price point of the clothing itself. On the other hand, when I think about Willi Smith’s collaborations with SITE or other artists, the relationship seems more exploratory, mutual, and productive (for both sides). He also seemed to pursue his ongoing collaborations with cutting-edge artists, architects, and designers with the goal of making the work even more broadly accessible, without necessarily raising its price point. Is it naive of me to think of this as a democratizing, almost collective, impulse?

JB:

PK:

JB:

I don’t think so. When he emerged in the seventies and through the eighties, he made a conscious decision to make clothes that were affordable for women. This really comes through when you see the clothes and know the price point. And in those days designers hadn’t collaborated with artists in this way. He created his own particular kind of storytelling in his clothes. I guess that’s what I’m trying to say. This was a very different story than the one being imparted in Yohji Yamamoto’s clothes. Or Steven Sprouse’s or Rei Kawakubo’s.

PK:

You mentioned before, Judith, that you hadn’t thought of his work in a long time. Forest, has his work come up more recently for you? Do you have any ideas around why it is that his work largely disappeared from view, and why it now seems relevant in our particular moment to rediscover it?

JB:

It might be because his clothes weren’t seen as valuable because you didn’t pay a lot of money for them, so you might not have saved them. Whereas you might collect an Armani suit for preservation and possibly sell it later as vintage. I think Willi anticipated our present moment when fashion would become unaffordable for the middle class. The moment we live in now needs WilliWear more than ever. He was designing clothes that appealed to a broad demographic as both fashionable and hip, and fun and affordable. Not many designers are able to do that.

FY:

Judith Barry is an artist and writer whose work crosses a number of disciplines—film/video, performance, installation, sculpture, architecture, photography, and new media—and she has exhibited internationally at such venues as the Berlin Biennale, Venice Biennale(s) of Art/Architecture, Sharjah Biennial, and São Paolo Biennial.

Prem Krishnamurthy is a designer, exhibition maker, teacher, and writer based in Berlin and New York. He is a partner of the design studio Wkshps (formerly Project Projects) and director of the exhibition space and curatorial practice P!.

Forest Young is a design leader, educator, and speaker. He is a global principal at Wolff Olins, which was recently named the Most Innovative Company for Design by Fast Company, and has led technological initiatives for the world’s influential companies and cultural institutions.

Today, collaborative creation is much faster and more transparent. If somebody is doing a collab, you’re going to hear about it on Instagram, and it’s probably going to have a hashtag and be on a work-back calendar that editors are looking at. And so collaboration has become, I wouldn’t say corrupted, but certainly monetized in the absolute sense. And I like Judith’s notion that Willi Smith is perhaps the designer that we most need in today’s climate. Someone who believes that any person desiring affordable and stylish comfort should have access to it; there is a beauty to this sentiment that for me forms a halo around the collections. Affordability today is not nearly as exquisite, or sincere. His clothing has an incredible humility both in terms of the simplicity of the construction and purity of the material, but also a genuinely selfless sense that they weren’t about him. They embody inclusivity without the need for a moniker.

Judith Barry is an artist and writer whose work crosses a number of disciplines—film/video, performance, installation, sculpture, architecture, photography, and new media—and she has exhibited internationally at such venues as the Berlin Biennale, Venice Biennale(s) of Art/Architecture, Sharjah Biennial, and São Paolo Biennial.

Prem Krishnamurthy is a designer, exhibition maker, teacher, and writer based in Berlin and New York. He is a partner of the design studio Wkshps (formerly Project Projects) and director of the exhibition space and curatorial practice P!.

Forest Young is a design leader, educator, and speaker. He is a global principal at Wolff Olins, which was recently named the Most Innovative Company for Design by Fast Company, and has led technological initiatives for the world’s influential companies and cultural institutions.