Style over Status

Lisa Yuskavage

In painting, nudity is timeless. The minute you decide to put a costume on a figure it becomes dated. Jeans and a T-shirt are not a particularly interesting thing to paint compared to a ruff collar or satin gown. In my earlier work, the costumes were made up for pictorial convenience, such as “beaded panties” where I made a series of colored dots on the crotch, because it worked for that painting.

I never want anything in my paintings to be generic or random. Everything has to have some sense of specificity in its relation to my history. In thinking about costumes, I remembered that growing up I almost never went shopping for clothes at a department store. Instead my mother took me to buy patterns and fabric, which she would sew into my outfits. It came from her being thrifty, but I was always dressed to the nines as a kid.

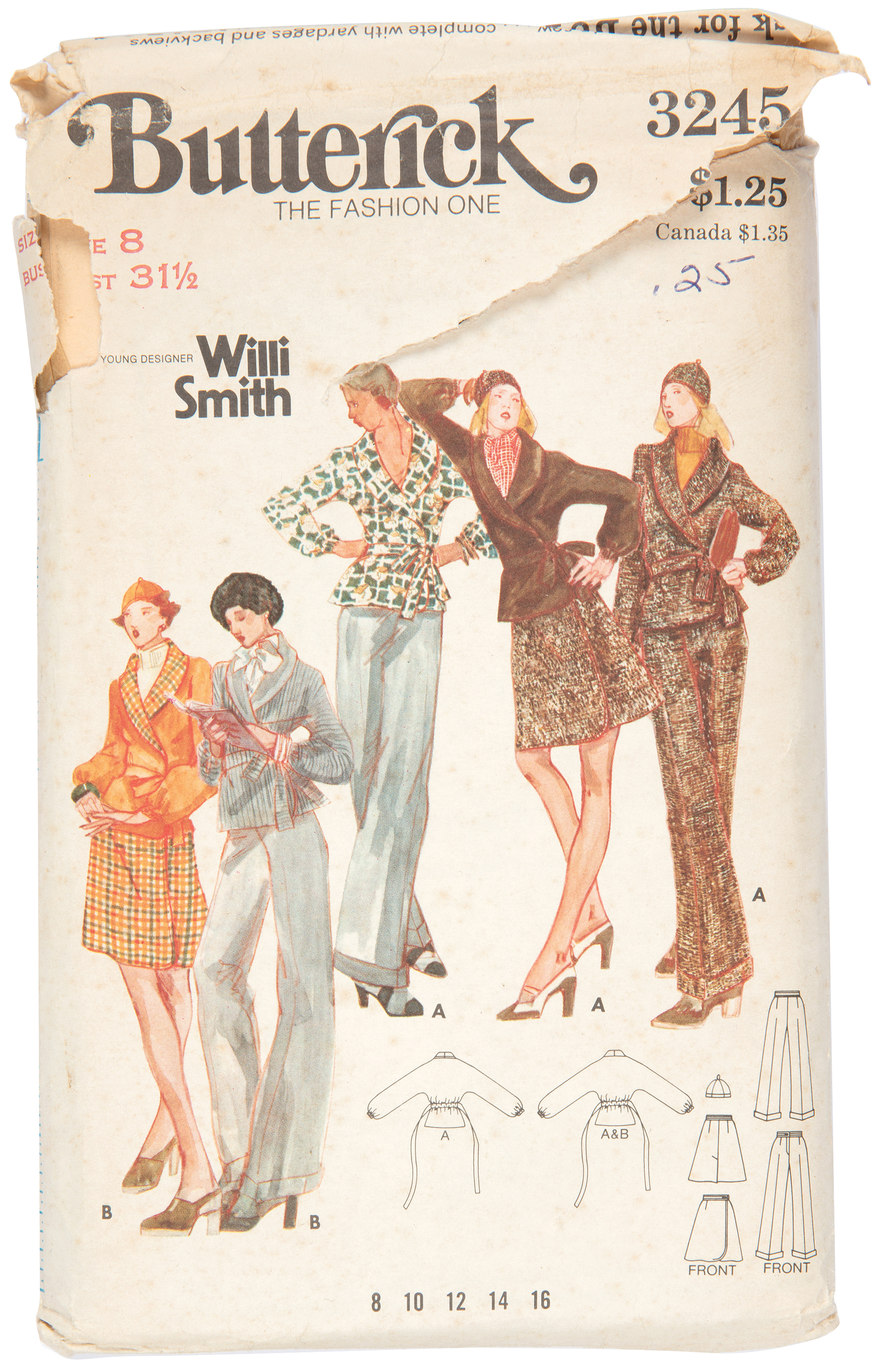

Growing up in North Philadelphia, I remember being mercilessly teased by the other kids because of how I dressed—very disco, polyester square pants and loose suede jackets with wide collars, flares. Always platform shoes with sequins. Come to think of it, kind of like a pimp. For my first day at the Philadelphia High School for Girls, I chose a Willi Smith pattern for my outfit: a vest and flared pants, as he did separates so well, with a Peter Pan collared blouse. I picked a fine rust corduroy fabric that went really well with the color of my hair, which I spent hours blow drying. Unbeknownst to me, I was voted best dressed white girl by the Black girls who made up the majority of the school. At the time, I did not understand that I was being dressed by a gay Black man. It’s the best look I ever had. I wish I had a photograph.

I never want anything in my paintings to be generic or random. Everything has to have some sense of specificity in its relation to my history. In thinking about costumes, I remembered that growing up I almost never went shopping for clothes at a department store. Instead my mother took me to buy patterns and fabric, which she would sew into my outfits. It came from her being thrifty, but I was always dressed to the nines as a kid.

What Willi Smith did was actually like tainting the water. He infiltrated culture.

Growing up in North Philadelphia, I remember being mercilessly teased by the other kids because of how I dressed—very disco, polyester square pants and loose suede jackets with wide collars, flares. Always platform shoes with sequins. Come to think of it, kind of like a pimp. For my first day at the Philadelphia High School for Girls, I chose a Willi Smith pattern for my outfit: a vest and flared pants, as he did separates so well, with a Peter Pan collared blouse. I picked a fine rust corduroy fabric that went really well with the color of my hair, which I spent hours blow drying. Unbeknownst to me, I was voted best dressed white girl by the Black girls who made up the majority of the school. At the time, I did not understand that I was being dressed by a gay Black man. It’s the best look I ever had. I wish I had a photograph.

Willi Smith for Butterick, Pattern 3245, 1973

Willi Smith for Butterick, Pattern 3245, 1973

This was before I went to art school and started painting

seriously, and the whole context of appearance shifted

for me—I wanted people to look at my art and not at me.

By the time I got to graduate school at Yale, I was far from

the best dressed girl, but my best friend there was an

older gay Black man who had been an art historian and

was going back for an MFA in painting. His name was

Jesse Murry. He had incredible panache, and I’ve always

been attracted to that kind of energy. Jesse died of AIDS

in 1993. Discovering Willi Smith and the impact he had on

my life that I didn’t even know about has made me think a lot about the people we lost and what they gave us—the

things we know about and the things we don’t even

realize. Because of Jesse, the story of AIDS has particular

meaning for me, and it seems to continue opening itself

up. I keep wanting to know more about the people we lost

to AIDS, because pretty much without exception, they

were an extraordinary group of people who did amazing

things and just got wiped out in the prime of their lives

for loving and being themselves. There is a kind of magic

for me in discovering this connection between Jesse and

Willi, and I love imagining them floating around together,

probably holding hands, continuing to connect people.

In the late nineties, I experimented with working from models and wanted to think of how to costume them, so I asked my mom for the patterns she had used for me. The cut, neckline, and sleeves were so distinctive. For their role in my paintings, I was interested in what they communicated about the characters, how clothes constructed the “type” of girl—the “innocence” and “girliness” of a frilly sleeve, or flowing blouse. Many of them were designed by Willi Smith, which didn’t mean anything to me at the time. In researching him later, I realized that he went to high school a few blocks from my house, so there was some deep cultural connection. Thinking back to wearing those clothes and being chased down the street by people in my neighborhood—they must have sensed that I was coming in contact with certain forces that were a little too posh and “exotic” for my ’hood.

In the late nineties, I experimented with working from models and wanted to think of how to costume them, so I asked my mom for the patterns she had used for me. The cut, neckline, and sleeves were so distinctive. For their role in my paintings, I was interested in what they communicated about the characters, how clothes constructed the “type” of girl—the “innocence” and “girliness” of a frilly sleeve, or flowing blouse. Many of them were designed by Willi Smith, which didn’t mean anything to me at the time. In researching him later, I realized that he went to high school a few blocks from my house, so there was some deep cultural connection. Thinking back to wearing those clothes and being chased down the street by people in my neighborhood—they must have sensed that I was coming in contact with certain forces that were a little too posh and “exotic” for my ’hood.

Lisa Yuskavage, Persimmons, 2006

Lisa Yuskavage, Persimmons, 2006

Lisa Yuskavage with her grandmother and her sister, Marybeth, Tyler School of Art graduation, Philadelphia, PA, 1980

Lisa Yuskavage with her grandmother and her sister, Marybeth, Tyler School of Art graduation, Philadelphia, PA, 1980One of Willi Smith’s quotes was “style over status.” That’s

important. Growing up, I didn’t have status, but through

his patterns, I had the ability to make myself look and feel

good. Some of my clothes were Willi Smith, but probably

some were people copying him, and I’m interested in that

too, as a form of influence. If he had believed in “status

over style,” someone like me would have never had

access to it. What Willi Smith did was actually like tainting

the water. He infiltrated culture. Through doing that, he

changed the world in a very significant way, though in a

way that is hard to measure. An exhibition and book like

this is trying to reconstruct that. It’s like pulling a very

complex marionette that’s got twisted strings, up from a

lying-down position. You have to do it carefully and you

know parts of it may not come back to life, but you have to

keep trying to animate it.

Lisa Yuskavage is an artist whose original approach to figurative painting has challenged conventional understandings of the genre. Her work has been exhibited at the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, Centre d’Art Contemporain, Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporáneo, the Royal Hibernian Academy, Dublin, and the Aspen Art Museum.

Lisa Yuskavage is an artist whose original approach to figurative painting has challenged conventional understandings of the genre. Her work has been exhibited at the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, Centre d’Art Contemporain, Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporáneo, the Royal Hibernian Academy, Dublin, and the Aspen Art Museum.