To Be American

Dario Calmese

In contrast to the restrictive and fantastical designs of the European fashion houses during his time, Willi Smith’s WilliWear exuded and evolved the core tenets of American design: comfort, utility, and durability. His garments sat alongside Calvin Klein and Donna Karan in Vogue spreads, and his loose, easy separates were a favorite among Japanese women seeking to emulate the relatively liberated lives of their U.S. counterparts. His suiting draped the shoulders of artist Edwin Schlossberg, the bridegroom of America’s princess, Caroline Kennedy, on their wedding day1 (a sly nod to Ann Lowe, the “Negro dressmaker” who designed the wedding gown for her mother, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis). And his keen adoption of cross-disciplinary collaborations and new media amplified the mass appeal of WilliWear’s democratic vision. Smith established a new archetype for U.S. design values that led to an internationally successful brand. So why have Black Americans continually struggled to maintain a foothold in the world of fashion design?

“It’s so hard to make the Black girls look expensive,” recalls designer Charles Harbison, referring to a conversation during his days as an assistant at Michael Kors. The brand had requested a Black model to come in for a fitting but was stumped deciding on a look that would elevate her enough for the show. “That experience stuck with me,” he said. Class, race, and aspiration have always collided within fashion; a spectacle to induce desire. Coded in the language of Harbison’s quote is the question, “Who would desire to be Black?”

“It’s so hard to make the Black girls look expensive,” recalls designer Charles Harbison, referring to a conversation during his days as an assistant at Michael Kors. The brand had requested a Black model to come in for a fitting but was stumped deciding on a look that would elevate her enough for the show. “That experience stuck with me,” he said. Class, race, and aspiration have always collided within fashion; a spectacle to induce desire. Coded in the language of Harbison’s quote is the question, “Who would desire to be Black?”

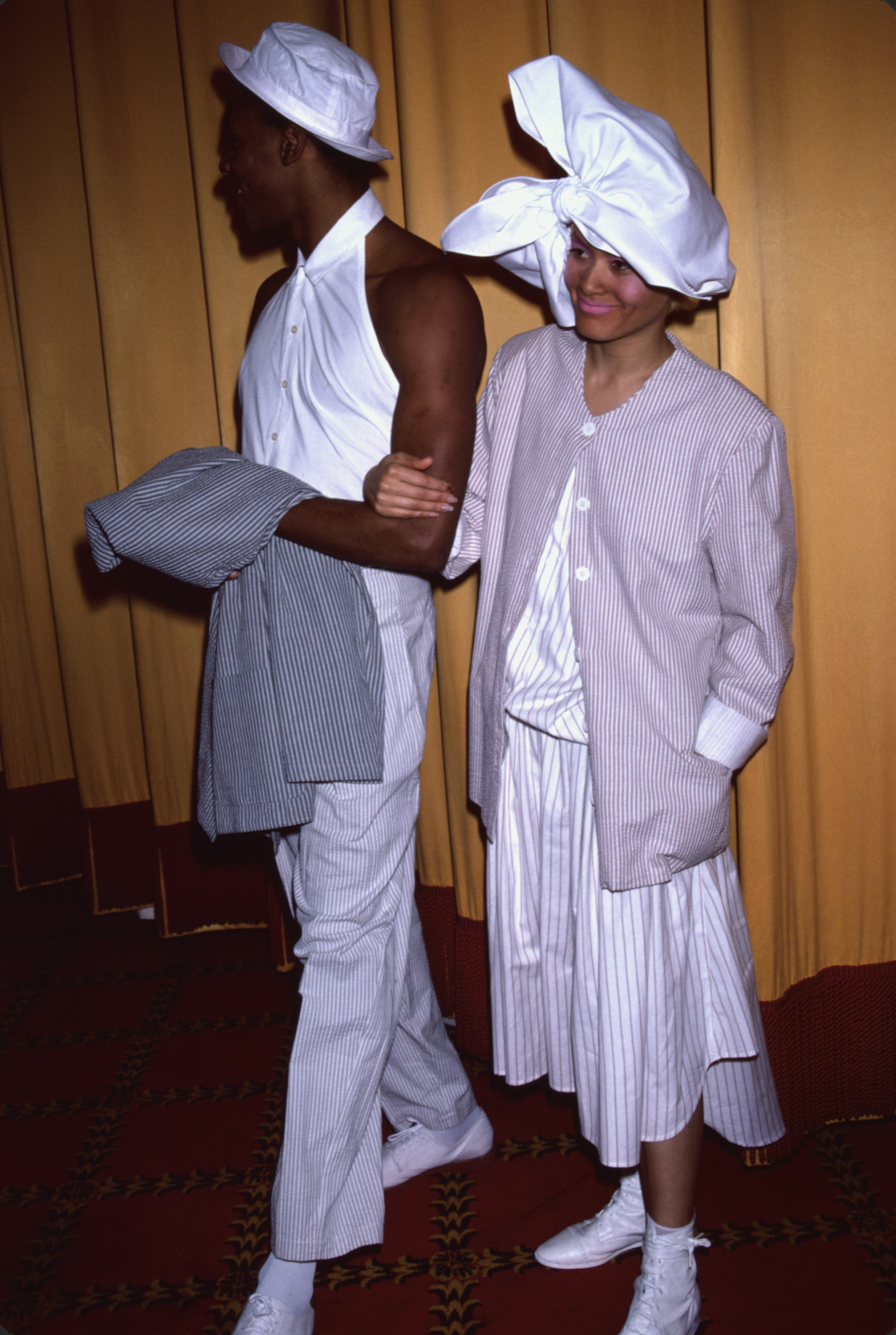

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Fall 1985 Presentation, Photographed by Peter Gould, 1985

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Fall 1985 Presentation, Photographed by Peter Gould, 1985

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring 1986 Presentation, Photographed by Peter Gould, 1985

In the introduction to his book of collected essays, Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin admits his internalized disdain for Negroes “because they failed to produce Rembrandt.”2 Reinterpreted in the world of U.S. fashion, one can ask, “Where is our Ralph Lauren?” However, the history of the fashion system and, more importantly, the history of the United States make that answer painstakingly clear. Since the late Middle Ages, fashion represented a concept of luxury, doused in opulent materials and stringent social protocol that was exclusive to aristocratic communities. “It was society ladies who put hats on other society ladies,” remarked fashion photographer Richard Avedon, referencing the style customs prominent in America and abroad at the funeral of his longtime collaborator, revered fashion editor Diana Vreeland.3 The term “society” is key to understanding that the fashion system was not constructed with Black people in mind. Avedon’s fateful meeting with Vreeland predated by two decades the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a piece of legislation meant to guarantee Black people full integration into U.S. society. Our Rembrandts have and do exist, but their creations have often been distributed through channels that dilute the source: Mary Todd Lincoln’s exquisite gowns, unattributed on lists of America’s most fashionable first ladies, were designed by Elizabeth Keckley, a former enslaved person; the wrap dress now associated with Diane Von Furstenberg began in Stephen Burrows’s studio. History is controlled by those in power.

Fashion is a hungry baby, and brands rely heavily on a motley crew of editors, writers, photographers, and investors to endorse brands. Today’s fashion shows cost upwards of $300,000, not including runway sample or staff salaries.4 Access to capital is the hobgoblin of the industry and can cripple designers, regardless of race; however, Black designers have often been held to a different standard, expected to convince investors that they have the taste level to dress society ladies as well as the acumen to run a sustainable business. Less than five percent of the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) members are Black.5

From Women’s Wear Daily’s sixties proclamation of the “Black explosion” to the miscategorization of many contemporary designers as “streetwear,” industry press coverage has been a double-edged sword, giving Black designers much-needed publicity while ghettoizing Black fashion production.6 “It’s upsetting, you know,” says Kerby Jean-Raymond, creative director of Pyer Moss in a 2016 interview with Elle magazine.7 “I’ve never seen Ralph Lauren, Rick Owens, or Raf Simons described as white designers.” In reference to the contemporary fashion press’s penchant for tossing Black design into the streetwear category, Jean-Raymond muses, “I just want to know what’s being called ‘street’—the clothes or me?” By continually categorizing designers based on race, the fashion press not only negates Black pluralism, but also flattens the dimensionality of their lives, experience, and creative output. Smith himself became weary of the monodimensional acknowledgment of designers of color. “You know, in the sixties and seventies there was this tremendous exposure given to designers based on their Blackness,” he states in a 1981 interview with Black Enterprise. “When the hype was over, people thought there were no more Black designers. In a way, it’s a blessing. Now we can get on with being what we are—designers.”8

Fashion is a hungry baby, and brands rely heavily on a motley crew of editors, writers, photographers, and investors to endorse brands. Today’s fashion shows cost upwards of $300,000, not including runway sample or staff salaries.4 Access to capital is the hobgoblin of the industry and can cripple designers, regardless of race; however, Black designers have often been held to a different standard, expected to convince investors that they have the taste level to dress society ladies as well as the acumen to run a sustainable business. Less than five percent of the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) members are Black.5

From Women’s Wear Daily’s sixties proclamation of the “Black explosion” to the miscategorization of many contemporary designers as “streetwear,” industry press coverage has been a double-edged sword, giving Black designers much-needed publicity while ghettoizing Black fashion production.6 “It’s upsetting, you know,” says Kerby Jean-Raymond, creative director of Pyer Moss in a 2016 interview with Elle magazine.7 “I’ve never seen Ralph Lauren, Rick Owens, or Raf Simons described as white designers.” In reference to the contemporary fashion press’s penchant for tossing Black design into the streetwear category, Jean-Raymond muses, “I just want to know what’s being called ‘street’—the clothes or me?” By continually categorizing designers based on race, the fashion press not only negates Black pluralism, but also flattens the dimensionality of their lives, experience, and creative output. Smith himself became weary of the monodimensional acknowledgment of designers of color. “You know, in the sixties and seventies there was this tremendous exposure given to designers based on their Blackness,” he states in a 1981 interview with Black Enterprise. “When the hype was over, people thought there were no more Black designers. In a way, it’s a blessing. Now we can get on with being what we are—designers.”8

At the time of Smith’s death, WilliWear generated more

than $25 million per year ($55 million in 2019 dollars)

and was carried in more than 1,100 global stores.9 Smith

subverted the spectacle Guy Debord described as the “unreal unity” masking “the class division on which the

real unity of the capitalist mode of production rests.”10 Via WilliWear, Smith upended the class divisions inherent

in the history of fashion by designing clothes not for the

queen but “for those who waved at her from the sidelines.”

His loose, liberated designs enhanced all body types, and

pieces were sold affordably. Beneath his genial manner,

Smith’s agenda was clear. “Who made the rule that everything in America that’s not expensive has to be horrible?”

he proclaimed to the Washington Post.11 Growing up watching the ways in which his mother and grandmother fashioned themselves, he understood that great style did not have to come at a great cost. The street, not bourgeois tastes, dictated trends. WilliWear flattened the fashion authority, undermining its aspirational reach and coating the white gaze with a Black aesthetic.

“When the hype was over, people thought there were no more Black designers. In a way, it’s a blessing. Now we can get on with being what we are—designers.”

In the nineties, after Smith’s passing, the garment

industry experienced a financial slump, which created a

space for voices that did not come through the traditional

fashion system. Brands like Karl Kani, Russell Simmons’s

Phat Farm, FUBU, and Cross Colours blossomed, epitomizing what was then called the “urban market.” Backed

by garmentos and the music industry, these brands

redefined streetwear and infused the industry with much

needed capital. This delineation between “fashion” and “streetwear” gave rise to brands like Sean Combs’s Sean

John and Baby Phat by Kimora Lee Simmons, which

sought to fuse the two worlds (Sean Combs went on to

win the CFDA Menswear Designer of the Year Award in

2004). Like Smith, they brought fashion to the streets, but while Smith designed for a broader clientele and

occasionally drew inspiration from Black culture, these

brands unapologetically centered Blackness in their

design aesthetic, branding, and target audience. However,

this alternative aesthetic, combined with a general lack of appreciation for the nuances of Blackness—within

fashion and America at large—would mark future Black

designers as “urban” despite their creative output.

The success of today’s cadre of Black designers continues to rely on subverting the fashion system. For his spring 2015 show, Jean-Raymond screened a fourteen-minute video showcasing police brutality before one model touched the runway with blood-splattered shoes. Virgil Abloh of Off-White and Louis Vuitton (LV) menswear used social media to usurp the fashion industry gatekeepers until the establishent itself came calling. Dapper Dan appropriated the codes of luxury by screen-printing LV and Gucci logos onto leather goods after the brands refused to allow him to sell their designs legitimately, a “hack” that predated LV ’s prêt-à porter line by thirteen years. He currently has his own Gucci atelier in Harlem. Even the demure Grace Wales Bonner engages the African diaspora through the lens of academia to quietly rewrite the codes of Black masculinity and reclaim the richness of Black culture via the American sportswear tradition. Donning loose, easy separates mixed with razor-sharp tailoring inspired by critical theory and Afro-Atlantic histories, her boyish and fey models not only redefined fashion’s ideal Black male (e.g., Tyson Beckford), but gave new voice to refinement Black peoples have always known and exhibited.

The history of fashion has been dominated by eurocentrism, hailing figures from Phillip the Good down to Alexander McQueen. Designed to advance privilege, the industry has repeatedly devalued the impact of Black peoples and Black culture. Smith’s efforts to connect art and industry, market through new media, and catalyze lifestyle and experience to create brand value laid the groundwork for the diverse voices breaking through industry protocol today. Contemporary Black designers are claiming their place in fashion history and the industry at large by writing a new narrative—not by those who control it, but by those who live it. Not for the queen, but for “those who wave at her from the sidelines.” This is America(n[a]).

The history of fashion has been dominated by eurocentrism, hailing figures from Phillip the Good down to Alexander McQueen. Designed to advance privilege, the industry has repeatedly devalued the impact of Black peoples and Black culture. Smith’s efforts to connect art and industry, market through new media, and catalyze lifestyle and experience to create brand value laid the groundwork for the diverse voices breaking through industry protocol today. Contemporary Black designers are claiming their place in fashion history and the industry at large by writing a new narrative—not by those who control it, but by those who live it. Not for the queen, but for “those who wave at her from the sidelines.” This is America(n[a]).

Dario Calmese is an artist, writer, director, and brand consultant currently based in New York City whose clients range from brands such as Pyer Moss and LaQuan Smith to publications including Vanity Fair and Numéro.

- Teresa M. Hanafin, “A Kennedy Is Wed, an Era Remembered,” Boston Globe (July 20, 1986).

- James Baldwin, opening essay in Notes of a Native Son (New York: Beacon Press, 1955)

- Michael Gross, The Secret, Sexy, Sometimes Sordid World of Fashions (New York: Atria Books, 2016).

- Fawnia Soo Hoo, “What a runway show really costs,” Vogue Business (February 5, 2019), Link.

- “CFDA Members,” CFDA, accessed June 1, 2019, Link.

- Sheila Banik, “Cutting on the Bias,” Black Enterprise 11, no. 12 (1981).

- Jessica Andrews, “Pyer Moss Designer Kerby Jean-Raymond Hates Being Labeled Streetwear,” Elle (February 12, 2016), Link.

- Banik, ibid.

- “Designer Willi Smith Dies,” Baltimore Afro-American (April 25, 1987).

- Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle (France: Buchet-Chastel, 1967).

- Gerri Hirshey, “Willi’s Way,” Washington Post Magazine, Style Section (1986).