Wedding Dress for the Black Fashion Museum

Elaine Nichols and Adrienne Jones

Willi Smith, Wedding Ensemble, ca. 1976–79

Willi Smith, Wedding Ensemble, ca. 1976–79

Throughout their lives, Willi Smith and Lois Alexander Lane worked in parallel to make fashion an inclusive and diverse industry. Smith advocated for the power of personal expression through his adaptable and affordable designs, while Alexander Lane built foundation for African American achievement in fashion. Various examples of Smith’s designs, including an unusual bridal ensemble, are preserved in Alexander Lane’s Black Fashion Museum (BFM) collection, which was donated to the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture in 2007 by Alexander Lane and her daughter Joyce Bailey.

Beginning in the late sixties, Alexander Lane created community-driven institutions that educated and promoted young, aspiring fashion designers. In 1966, she founded the Harlem Institute of Fashion (HIF) to teach African American students Black history, ways to improve their reading, writing, and math skills, and how to navigate the fashion industry.1 In 1979, Alexander Lane established the BFM to provide visual proof that African Americans contributed to the world of fashion from the period of slavery to the modern era. Her work as a historian, organizer, and activist nurtured and preserved Black fashion history. The BFM collection serves as an invaluable resource for understanding the works of Ann Lowe, Geoffrey Holder, Patrick Kelly, Stephen Burrows, and Willi Smith, among many others.2

In 1981, Alexander Lane mounted a seminal exhibition at the BFM entitled Bridal Gowns by Black Designers. Among the numerous traditional gowns was Willi Smith’s rajah-style cotton satin jacket and beige-colored velveteen jodhpurs. It captured the progressive spirit of the time, boldly bent the lines of gender, identity, and cultural dress, and challenged standards for one of society’s most sacred global ceremonies.3

Beginning in the late sixties, Alexander Lane created community-driven institutions that educated and promoted young, aspiring fashion designers. In 1966, she founded the Harlem Institute of Fashion (HIF) to teach African American students Black history, ways to improve their reading, writing, and math skills, and how to navigate the fashion industry.1 In 1979, Alexander Lane established the BFM to provide visual proof that African Americans contributed to the world of fashion from the period of slavery to the modern era. Her work as a historian, organizer, and activist nurtured and preserved Black fashion history. The BFM collection serves as an invaluable resource for understanding the works of Ann Lowe, Geoffrey Holder, Patrick Kelly, Stephen Burrows, and Willi Smith, among many others.2

In 1981, Alexander Lane mounted a seminal exhibition at the BFM entitled Bridal Gowns by Black Designers. Among the numerous traditional gowns was Willi Smith’s rajah-style cotton satin jacket and beige-colored velveteen jodhpurs. It captured the progressive spirit of the time, boldly bent the lines of gender, identity, and cultural dress, and challenged standards for one of society’s most sacred global ceremonies.3

Though little is known about what motivated Smith’s design of the BFM ensemble, possible influences include his experience as a protégé of noted couturier Arthur McGee, whose own non-traditional bridal wear quoted numerous Asian aesthetics, and Smith’s well-documented business and personal interests in India. Smith’s frequent trips to Bombay to oversee design and production with WilliWear manufacturers led to collections that borrowed from traditional Indian garments, such as turbans, cholis, saris, and salwar kameez. His interpretation of dhoti pants became a WilliWear icon.

Like these early WilliWear designs, the BFM ensemble includes an admixture of what were accepted as male and female symbols of dress interpreted through a global lens. The coat resembles a man’s sherwani with a Nehru collar and five functional buttons on the left placket. In the seventies when this jacket was made, placement of buttons on the left side of a garment indicated that it was intended for female wearers. Another symbol of femininity is the jacket’s delicately gathered and flared skirt with a narrow matching belt that, when tied, hangs almost the complete length of the skirt. A decade later, Smith added a headdress by David Madison. Made of pussy willow, statice, and chair caning, this unconventional accessory resembles a woman’s fifties/sixties round, bucket-style or floral pouf hat. The ensemble is completed by masculine pants, more specifically jodhpurs—riding trousers named for a city in the state of Rajasthan in northern India, and historically worn by men of royal or noble birth for weddings, formal occasions, and sporting events.

Like these early WilliWear designs, the BFM ensemble includes an admixture of what were accepted as male and female symbols of dress interpreted through a global lens. The coat resembles a man’s sherwani with a Nehru collar and five functional buttons on the left placket. In the seventies when this jacket was made, placement of buttons on the left side of a garment indicated that it was intended for female wearers. Another symbol of femininity is the jacket’s delicately gathered and flared skirt with a narrow matching belt that, when tied, hangs almost the complete length of the skirt. A decade later, Smith added a headdress by David Madison. Made of pussy willow, statice, and chair caning, this unconventional accessory resembles a woman’s fifties/sixties round, bucket-style or floral pouf hat. The ensemble is completed by masculine pants, more specifically jodhpurs—riding trousers named for a city in the state of Rajasthan in northern India, and historically worn by men of royal or noble birth for weddings, formal occasions, and sporting events.

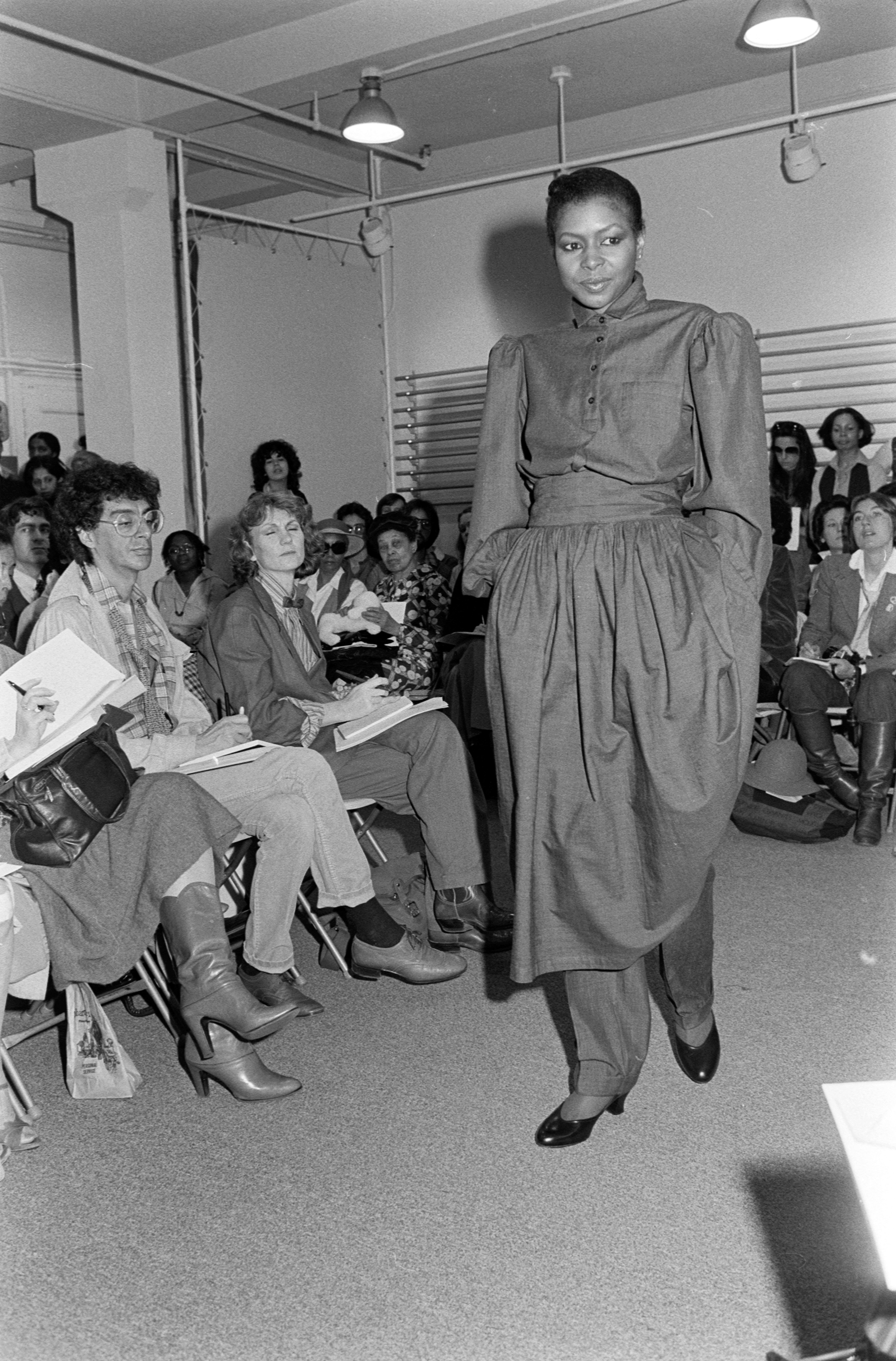

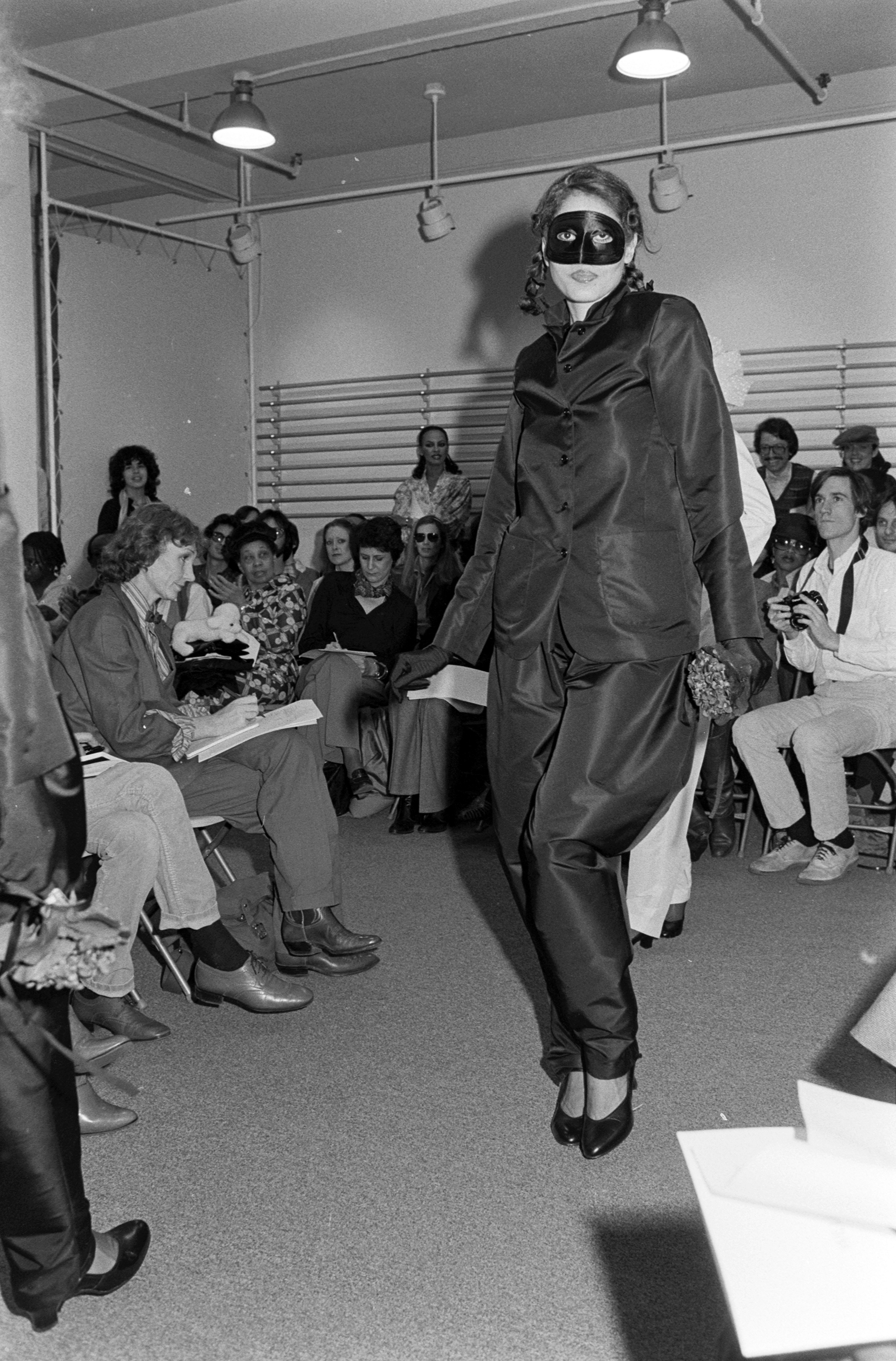

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Fall 1978 Presentation, 1978

Although WilliWear was recognized for its gender fluidity, Smith typically used the opportunity to design wedding attire for friends and collaborators to indulge in ultra feminine silhouettes with high necks, bare shoulders, and voluminous fishtails layered in silk and tulle. Smith’s rajah wedding ensemble is a rare example of his moving away from Western matrimonial traditions. It represents stylistic, gendered, and ethnic inclusion, personal empowerment, and “control of the self by the wearer,” rather than subversive resistance to the norm.4 This celebration of individuality and freedom of expression is what made Smith one of the most successful designers of his time.

Elaine Nichols is the supervisory curator of culture at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). Nichols has also worked at the South Carolina State Museum as curator of history.

Adrienne Jones is a professor at Pratt Institute. Jones holds degrees in Art Therapy (M.S.), Art Education (B.S.), Fashion Design (A.A.S.), and has won many awards and honors, including being presented with the Innovative Visionary Icon of the Decade by African American Wome in Cinema, in 2015.

Adrienne Jones is a professor at Pratt Institute. Jones holds degrees in Art Therapy (M.S.), Art Education (B.S.), Fashion Design (A.A.S.), and has won many awards and honors, including being presented with the Innovative Visionary Icon of the Decade by African American Wome in Cinema, in 2015.

- Elaine Nichols, “Something Beautiful and Useful: The Work of Lois Kindle Alexander Lane and the Black Fashion Museum Collection at the NMAAHC,” unpublished research paper, April 27, 2015; Renee Minus White, “Harlem Institute of Fashion: Focus on Fashion,” New York Amsterdam News (October 30, 1976), Link.

- Nichols, ibid.

-

Ozeil Fryer Woolcock, “Social Swirl: Black Fashion Museum Founder Was in Atlanta,” Atlanta Daily World (September 20, 1981), Link; BFM Archives, NMAAHC, “A Stitch in Time, 1800−2000,” Box 150, Folder 2, #12.

- Carol Tulloch, “‘My Man, Let Me Pull Your Coat to Something’: Malcolm X,” in The Birth of Cool: Style Narratives of the African Diaspora (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), 127-50.