Willi Smith In Pieces

Jarrett Earnest

Willi Smith, Photographed by Rosemary Peck, ca. 1982

Willi Smith, Photographed by Rosemary Peck, ca. 1982I.

In August 1972, as the artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude were preparing to unfurl 200,200 square feet of orange nylon between two Colorado mountains, they received a phone call from a young friend in New York, the designer Willi Smith. He wanted to join them. They told him it wasn’t easy to get there—he’d have to fly to Denver, take a bus six hours to Grand Junction, then another for an hour and a half to the town of Rifle, seven miles from the site. He was undeterred. They were delighted. A pair of radical conceptual artists with thick European accents, Christo and Jeanne-Claude were exotic in the rural American West. It would be good to have the company of a fellow cosmopolitan. Then Jeanne-Claude got nervous. She hadn’t seen any Black people in the region. How would the locals react? When she hadn’t heard from him on the afternoon of his arrival, she went to Rifle to investigate. At the town’s cowboy bar she found Smith at the center of a group talking and laughing together. He was festooned with a monkey-fur coat with a crossed-pistol belt buckle.1Smith, then in his early twenties, was already prominent as a designer at the label Digits and a habitué of New York’s art and fashion worlds but little known otherwise. That started to change when he got a call from Laurie Mallet, a student of political science and economics in Paris who was trying to subsidize a New York holiday by selling French textiles to American designers. The two met and instantly liked each other. He hired her as an assistant when she moved to New York. By the mid-seventies they’d both left Digits and were going out on their own, Mallet running a textile company that manufactured shirts out of cotton gauze and Smith planning to launch a brand. She proposed that they travel to India to source fabric. He could design a line they’d put into production, which later she’d figure out how to sell. On the trip, he drew a cartoon of them smiling together, his arm resting on her shoulder and hers wrapped around his waist holding a cigarette emitting a squiggle of smoke. A single line shaped the curves of an unfamiliar skyline “Bombay—1976” is written in the upper left corner, with a little rectangle drawn below it that would evolve into the logo of their joint venture: WilliWear Ltd.

Willi Smith, Drawing of Willi Smith and Laurie Mallet, 1976

Willi Smith, Drawing of Willi Smith and Laurie Mallet, 1976

Mallet immediately bonded with Smith’s friends Jeanne-Claude and her husband, among others in a growing tribe of WilliWear collaborators. In 1983, when Christo and Jeanne-Claude were about to surround eleven islands in Miami’s Biscayne Bay with floating hot pink polypropylene, WilliWear produced pink long-sleeve shirts with the words “Christo Surrounded Islands” in sky-blue ink on the back left shoulder and matching white caps with cotton flaps down the back. The shirts were worn by the 430 members of the workforce and 120 monitors who patrolled the area during the two weeks of the installation. Several thousand extras made for sale as souvenirs were shopped to stores in Miami, every one of which turned them down, so they were sold off the back of a truck. The shirts proved to be a smash. They complemented Christo’s art of real-world, festive pleasures, accessible to everyone, extending the project beyond the bay and into the city. Then, like countless amateur snapshots that documented the two-week artwork, the shirts assumed an afterlife as mementos.

The experience of Surrounded Islands excited Smith and Mallet to seek collaboration with other contemporary artists in the same avant garde dream of bringing the spirit of “high art” into the lives of regular folks. They reached out to about twenty artists to design T-shirts, including figures of the sixties generation, each in their way dedicated to bridging art and life—Robert Rauschenberg, Les Levine, Nam June Paik, and Arman. WilliWear extended this list to the graffiti artists Dondi, Futura, and Keith Haring, and to such emerging conceptualists as Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, and Lynn Hershman. Completing the artistic family were Christo; SITE; Mallet’s stepfather, the painter Severo, and her then boyfriend, the designer Dan Friedman. The shirts by the cohort, framed and cellophane wrapped, priced at thirty-seven dollars and one-size-fits-all, were shown at the Ronald Feldman Gallery in the summer of 1984.

Barbara Kruger knew of Willi Smith from her work as an editorial designer in the seventies at the counterculture magazine Rags and then at Condé Nast’s Mademoiselle. Relatively unknown as an artist, she jumped at the opportunity offered by WilliWear. Her shirt sports a black-and-white face—eyebrows and lips feminized with heavy cosmetics. Across the eyes runs a slanted black bar with white text: “I can’t look at you.” Another completes the phrase below the chin: “and breathe at the same time.” When one encounters the shirt on a body moving down the street, the image and the captions become legible at different speeds. Interpretation is further shaped by impressions of the person wearing it. Kruger said that the idea of the garment’s accessibility, traveling freely through culture, appealed to her conceptually: “The way people wear corporate logos or political slogans on their clothes is a kind of public construction that displays the broadcast of self, replete with affiliations and hierarchies, and congeals quite simply into both the brilliance and idiocy of fashion.”2

The experience of Surrounded Islands excited Smith and Mallet to seek collaboration with other contemporary artists in the same avant garde dream of bringing the spirit of “high art” into the lives of regular folks. They reached out to about twenty artists to design T-shirts, including figures of the sixties generation, each in their way dedicated to bridging art and life—Robert Rauschenberg, Les Levine, Nam June Paik, and Arman. WilliWear extended this list to the graffiti artists Dondi, Futura, and Keith Haring, and to such emerging conceptualists as Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, and Lynn Hershman. Completing the artistic family were Christo; SITE; Mallet’s stepfather, the painter Severo, and her then boyfriend, the designer Dan Friedman. The shirts by the cohort, framed and cellophane wrapped, priced at thirty-seven dollars and one-size-fits-all, were shown at the Ronald Feldman Gallery in the summer of 1984.

Barbara Kruger knew of Willi Smith from her work as an editorial designer in the seventies at the counterculture magazine Rags and then at Condé Nast’s Mademoiselle. Relatively unknown as an artist, she jumped at the opportunity offered by WilliWear. Her shirt sports a black-and-white face—eyebrows and lips feminized with heavy cosmetics. Across the eyes runs a slanted black bar with white text: “I can’t look at you.” Another completes the phrase below the chin: “and breathe at the same time.” When one encounters the shirt on a body moving down the street, the image and the captions become legible at different speeds. Interpretation is further shaped by impressions of the person wearing it. Kruger said that the idea of the garment’s accessibility, traveling freely through culture, appealed to her conceptually: “The way people wear corporate logos or political slogans on their clothes is a kind of public construction that displays the broadcast of self, replete with affiliations and hierarchies, and congeals quite simply into both the brilliance and idiocy of fashion.”2

Contemporary artists had never before collaborated with a fashion label to create industrially produced clothes, a strategy now ubiquitous in fashion culture. Smith thought people were intimidated by art museums. Of the collaborations he said: “This way we are bringing the artist closer to the people. It’s really street art. I want to see us involved more with art in the community.”3 Keith Haring echoed the sentiment when describing the aims of his Pop Shop, which opened in 1986: “I wanted to continue this same sort of communication as with the subway drawings. I wanted to attract the same wide range of people, and I wanted it to be a place where, yes, not only collectors could come, but also kids from the Bronx. . . . The main point was that we didn’t want to produce things that would cheapen the art. In other words, this was still an art statement.”4

![Laurie Mallet, Willi Smith, and Dan Friedman at The Pont-Neuf Wrapped, Photographed by Mark Bozek, 1985]() Laurie Mallet, Willi Smith, and Dan Friedman at The Pont Neuf

Wrapped, Photographed by Mark Bozek, 1985

Laurie Mallet, Willi Smith, and Dan Friedman at The Pont Neuf

Wrapped, Photographed by Mark Bozek, 1985

![]()

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Pont-Neuf Wrapped, Photographed by Wolfgang Volz, 1985

Laurie Mallet, Willi Smith, and Dan Friedman at The Pont Neuf

Wrapped, Photographed by Mark Bozek, 1985

Laurie Mallet, Willi Smith, and Dan Friedman at The Pont Neuf

Wrapped, Photographed by Mark Bozek, 1985

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Pont-Neuf Wrapped, Photographed by Wolfgang Volz, 1985

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Surrounded Islands Construction Site, Photographed by Wolfgang Volz, 1983

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Surrounded Islands Construction Site, Photographed by Wolfgang Volz, 1983 Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Surrounded Islands, Photographed by Wolfgang Volz, 1983

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Surrounded Islands, Photographed by Wolfgang Volz, 1983

In 1985 Christo and Jeanne-Claude finally succeeded in a ten-year campaign to wrap the Pont Neuf. If pink T-shirts were right for scrappy South Floridians, the workers engaging visitors on the oldest bridge in Paris needed something more elegant. Smith designed a loose-fitting sky-blue smock, riffing on the iconic bleu de travail French work jacket, with matching trousers, the blue outfits playing off the tawny champagne of the bridge’s ruched material. Oversized pockets, hung low, could accommodate fabric samples and informational brochures. Like all of Smith’s clothing, it was comfortable and adaptable, for wearing with rolled sleeves or hiked legs or unbuttoned with an undershirt. It was a professionalizing uniform that allowed for maximum individuality. Interviewed at the time, Smith said: “I’m also looking forward to seeing if people can really work in the clothes. I could eventually make some real workwear. . . . Everyone likes the style so much I may put it on the spring line. It may be a new way to develop our artist-in-clothing project.”5 At one point, Christo showed him an advertisement in a Paris newspaper for one of the uniforms. The price: $1,000. Smith laughed and said, “Oh! Now I’m haute couture!”6

“My whole theory about design is to try to solve some of these problems,” Smith once said. “To help people through clothing to solve the problem of getting dressed.”7 The concern wasn’t limited to celebrities on their way to galas. He had devoted himself from the start, in the early seventies, to finding solutions within the reach of almost anyone. One way was to make his designs available as patterns through services like Butterick and McCall’s, a practice that spanned his entire career. He valued people who sewed their own clothes at home, as members of his family had done in working-class Philadelphia. He explained: “To be able to go and buy the fabric. Already you have one exciting purchase—you bought beautiful fabric—and you get excited about that. You might take it home and may not even buy the pattern for two weeks later. Then you go and buy something else which you are equally excited about which is the pattern. And then the excitement of putting it together. It’s like a whole different way of dressing than buying clothes.

Willi Smith in Palm Springs, CA, Photographed by Rosemary Peck, ca. 1982

“Buying clothes is a one-time thing. You go in and buy something, take it home. You may like it, you may hate it the next minute, it’s a one-time thing. This is a multiple experience, I think. I know, a lot of girls say to me, ‘We really dig your stuff a lot, but sometimes we can’t afford to buy all that we would like to buy,’ so I had no answer for them. Now I feel through this medium that I do.”8 Meanwhile, disdaining to build an elite identity around fashions unwearable in daily life, for one thing, and inaccessible to all citizens, for the clincher, Smith concentrated on designing budget-priced clothes for sale at regular department stores.

“‘Fashion’ was a word we hardly ever used,” recalls Bethann Hardison, who Smith “discovered” walking down Seventh Avenue in 1967, and instantly recruited as model, collaborator, and friend. She understood Smith’s approach to style as holistic, a larger attitude toward being creative than the term “fashion” might imply. “It wasn’t so much he wanted to change the way we looked at fashion,” she says. “It was a way of seeing how much further you can push it. How many more ways you can utilize something, create. So he happened to be a designer, but he was an artist. That is why he appreciated artists so much. Anything he could do—including patterns—was another way of changing what you could get people to see.”9

“‘Fashion’ was a word we hardly ever used,” recalls Bethann Hardison, who Smith “discovered” walking down Seventh Avenue in 1967, and instantly recruited as model, collaborator, and friend. She understood Smith’s approach to style as holistic, a larger attitude toward being creative than the term “fashion” might imply. “It wasn’t so much he wanted to change the way we looked at fashion,” she says. “It was a way of seeing how much further you can push it. How many more ways you can utilize something, create. So he happened to be a designer, but he was an artist. That is why he appreciated artists so much. Anything he could do—including patterns—was another way of changing what you could get people to see.”9

This manifested in his commitment to “basics” that could be worn in many combinations, styled up or down for the occasion, by the person getting dressed. It’s a philosophy further summarized by Mallet: “There is nothing worse than wearing a designer outfit and not feeling good because it’s not you, it’s the designer’s. Once they were sold they were not Willi’s clothes anymore, they became yours. His great talent was creating clothes that you could own.”10

II.

Rosemary Peck remembers first hanging out with Willi Smith in the early seventies. She had just moved with her three children back to New York from Roslyn, Long Island, to pursue her burgeoning jewelry business. The two met through a mutual friend, designer Harriet Selwyn, who had worked with Willi at Digits. One day he invited Rosemary to his apartment on Horatio Street. They talked the day away: he told her about being raised by his grandmother, Gladys Bush, who had worked as a housekeeper to put him through school, supporting his dream of becoming a designer; Rosemary told him about her divorce and how she had started making jewelry to have a life on her own; they fell quiet at times, comfortable being together.

Jerry Isenberg, Willi Smith, Rosemary Peck, and Harriet Selwyn in Los Angeles, CA, Photographed by Jean Desaarin, 1980

Over the next decade he regularly phoned her at her duplex in Chelsea, joined her and her kids for family dinners, and invited her out to see kabuki or to go dancing at downtown clubs. They became part of each other’s families—she hired his mother, June, to help with her jewelry, often traveled with his younger sister Toukie, and met Nana Bush in Philadelphia. Their scene was raucous and extremely social, but she increasingly noticed Smith’s heavy drinking, which helped him cope with the demands of his public life. When Rosemary took a house with an art studio in Joshua Tree, California, in the early eighties, Willi came for Christmas. Because it was the desert, he brought shorts and only light clothes. He was shocked when it snowed. After a drive into Palm Springs to find him something warmer, Rosemary took a picture. In a landscape lightly dusted with white, Willi wears gray sweats, a dark jacket, and a white scarf and holds sketchbooks under one arm. He gazes at her through the lens with vivid affection, beaming. During that visit, he drew her at work painting. She is turned away, contrapposto, with arms and legs at jaunty angles. The style of the drawing recalls the softness of sketches by Christian Bérard, with marks moving in and out of smudges in negative space. The touch is light, immediate, intimate.

“There is nothing worse than wearing a designer outfit and not feeling good because it’s not you, it’s the designer’s. Once they were sold they were not Willi’s clothes anymore, they became yours. His great talent was creating clothes that you could own.”

Theirs was a romance without sex. In matters of style, they were soulmates, bonding over what they found beautiful and sharing an instinct for how to put things together. Smith invited her back to New York to live with him while she decorated his new apartment on Lispenard Street, on the other side of Canal Street from Christo and Jeanne-Claude. He had a collection of African antiques and contemporary art but very little furniture. One night, as they walked home from dinner in Chinatown, Rosemary spotted a stack of battered wooden shipping pallets. She knew they’d work. Smith hired a passerby to help and they brought two to the loft. Snapshots show one used as a coffee table holding a large potted plant, an arrangement of Japanese vessels, an African bust, and a 1978 work by Christo (a wrapped copy of the book Modern Art by Sam Hunter and John Jacobus). The scavenged pallet served those objects well and communed at ease with an Alvar Aalto chair and a wall arrayed with prints from Christo’s series (Some) Not Realized Projects (1971).

Willi Smith, Sketch of Rosemary Peck, 1982

Interior of Willi Smith’s Lispenard Street Loft, Photographed by Rosemary Peck, 1986

Interior of Willi Smith’s Lispenard Street Loft, Photographed by Rosemary Peck, 1986

Interior of Willi Smith’s Lispenard Street Loft, Photographed by Rosemary Peck, 1986

New York magazine celebrated the apartment in “Special Effects,” a twenty-five-page photo-essay by Marilyn Bethany and Oberto Gili, on the reemergence of the “artist craftsman” in interior design (the magazine’s cover was an image of SITE’s remodel of Laurie Mallet’s townhouse).11A six-page spread of Willi’s airy loft called it “artlessly artful”: the walls and couch were white and the furniture and art predominantly black, with painted zebra rugs splitting the difference. The look typified Rosemary’s graphic design aesthetic, favoring white walls as grounds for the color accents of flowers and of people moving in and out of the rooms. The space is fluidly changeable—alive. A large Keith Haring drawing of interlocking figures hangs with the Christo prints. The Modern Art piece occupies a dark green coffee table shaped like the continent of Africa, designed by Dan Friedman. White orchids, Willi’s favorite, abound. Rosemary remembers teasing him that he must have been a prince in a former life. He laughed and said, “Only a prince?!”12

Around the same time, in the spring of 1986, Willi’s mother died. They were very close, but his feelings around her were complex. Many times through the years he and Rosemary had commiserated with one another’s heart-breaks, but dealing with this far heavier blow deepened their bond. For her birthday that May he gave her an advance copy of Susan Vogel’s landmark book African Aesthetics, inscribed: “To my dear friend Rosemary, When I think of beautiful things I think only of you. Losing my mom at this time I feel even closer to you emotionally and spiritually. I really love you Rosemary and value our growing friendship. Happy fifty. . . . love Willi.”

Later that year he visited her new place on Rossmore Avenue in Los Angeles, which she had done up in a California version of a Park Avenue interior. Willi had finally gone to the Betty Ford clinic and gotten sober. He looked like a movie star. When she told him so, he laughed, saying that he’d actually been thinking of working in film, both in front of and behind the camera. On the morning of his return to New York, Willi proposed to her. “We could share a beautiful life together. . . .” She played it off. Then he mentioned that he had a lump at the back of his neck. Rosemary put her hand there. The glands were swollen. Neither uttered the word “AIDS,” but it occurred to her. Driving him to the airport, she took a wrong turn and wound up in Long Beach. She later attributed this to an unconscious wish that he not leave. The next day he flew to India for a month. Upon his return, in early 1987, he told Rosemary over the phone that on the Ganges he had felt someone tap him on the shoulder. It was his mother.

Just before Rosemary left on a business trip to Brazil with Harriet Selwyn, Bethann called in tears. “Rosie, our brother Willi is not well,” she said.

Rosemary remembers begging Harriet to cancel their trip, but it was all arranged and paid for and they had to go. Once she got to the hotel in Brazil a woman approached her, asked her name, and told her she’d had calls. They left that night for New York. On Friday, April 17, 1987, a day after being admitted to Mount Sinai Medical Center, Willi Smith died. He was thirty-nine years old.

Around the same time, in the spring of 1986, Willi’s mother died. They were very close, but his feelings around her were complex. Many times through the years he and Rosemary had commiserated with one another’s heart-breaks, but dealing with this far heavier blow deepened their bond. For her birthday that May he gave her an advance copy of Susan Vogel’s landmark book African Aesthetics, inscribed: “To my dear friend Rosemary, When I think of beautiful things I think only of you. Losing my mom at this time I feel even closer to you emotionally and spiritually. I really love you Rosemary and value our growing friendship. Happy fifty. . . . love Willi.”

Later that year he visited her new place on Rossmore Avenue in Los Angeles, which she had done up in a California version of a Park Avenue interior. Willi had finally gone to the Betty Ford clinic and gotten sober. He looked like a movie star. When she told him so, he laughed, saying that he’d actually been thinking of working in film, both in front of and behind the camera. On the morning of his return to New York, Willi proposed to her. “We could share a beautiful life together. . . .” She played it off. Then he mentioned that he had a lump at the back of his neck. Rosemary put her hand there. The glands were swollen. Neither uttered the word “AIDS,” but it occurred to her. Driving him to the airport, she took a wrong turn and wound up in Long Beach. She later attributed this to an unconscious wish that he not leave. The next day he flew to India for a month. Upon his return, in early 1987, he told Rosemary over the phone that on the Ganges he had felt someone tap him on the shoulder. It was his mother.

Just before Rosemary left on a business trip to Brazil with Harriet Selwyn, Bethann called in tears. “Rosie, our brother Willi is not well,” she said.

“I know, he got a parasite in India.”

“No, it’s much worse than that. . . .”

Rosemary remembers begging Harriet to cancel their trip, but it was all arranged and paid for and they had to go. Once she got to the hotel in Brazil a woman approached her, asked her name, and told her she’d had calls. They left that night for New York. On Friday, April 17, 1987, a day after being admitted to Mount Sinai Medical Center, Willi Smith died. He was thirty-nine years old.

III.

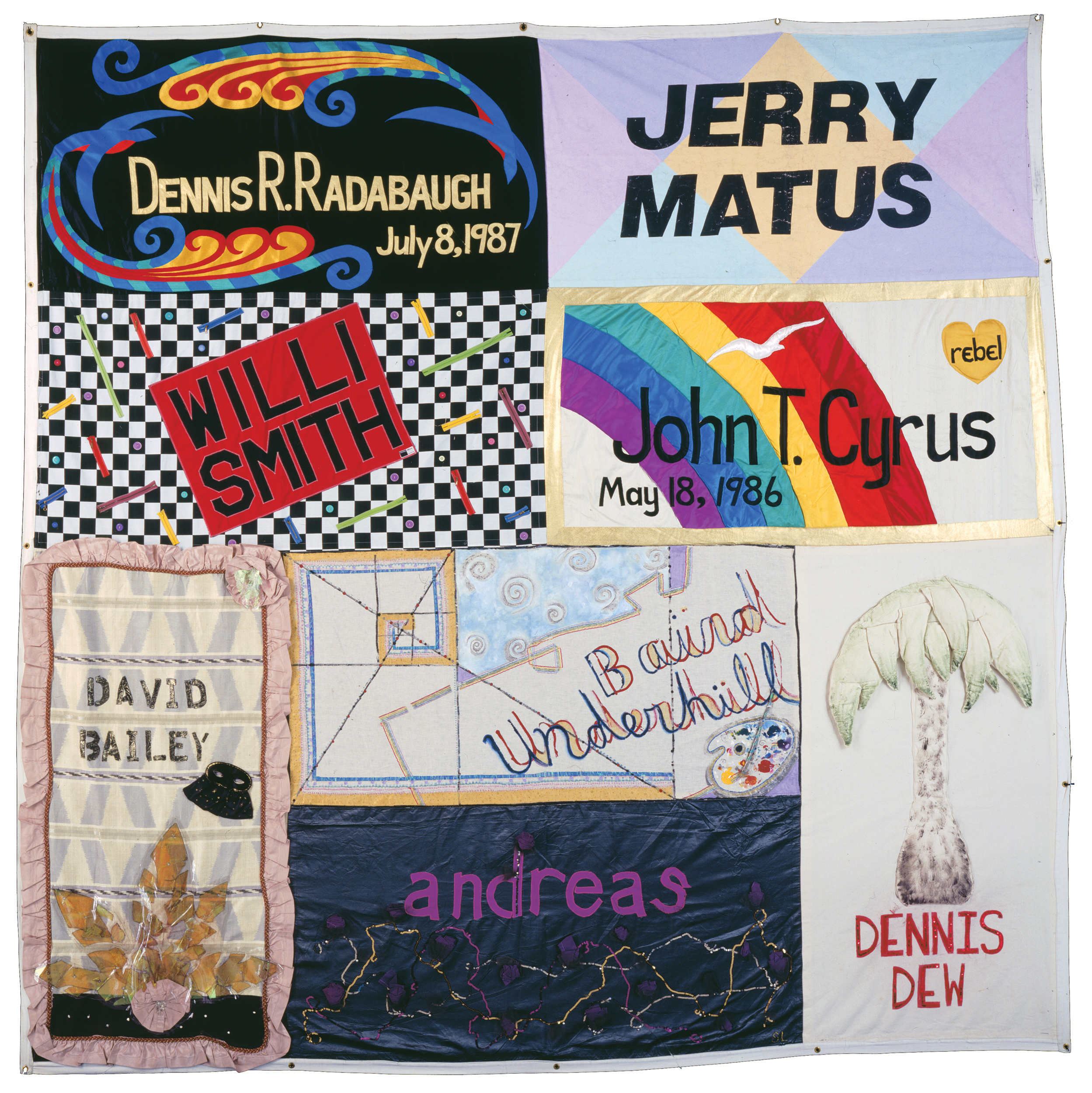

Working nights as a telephone operator in San Francisco, Rod Shelnutt began volunteering as floor manager for the Quilt’s workshop during the day, after losing fourteen friends to AIDS. He had been sewing since he was eleven, starting with outfits for his little sister and then, when making clothes for himself, using Willi Smith patterns. News of Smith’s death was a shock. Shelnutt set to making a panel: black-and-white checkerboard with a central slanted rectangle that read “WILLI SMITH” against a red background. Zigzagging around were neon zippers in yellow, red, green, and blue, and buttons in purple, pink, and aqua. Shelnutt cut the WilliWear label out of one of his tank tops and sewed it on below the name. “I made this for Willi Smith not just because he was a celebrity,” he said, “but because he had a real effect on my life.”13

NAMES Project Quilt, 1988

Back issues of magazines in library basements; random slides, contact sheets, photographs in institutional and personal collections; vintage paper patterns you can find online; and shockingly few surviving clothes across the country—that’s what remains of Willi Smith. People consistently tell of wearing their WilliWear for years until it wore out. In 2018, the Pérez Art Museum Miami mounted a documentary exhibition about Surrounded Islands on the installation’s thirty-fifth anniversary.

The show attracted and excited local people who had never experienced contemporary, let alone conceptual, art. Many who had seen the work in situ showed up at the museum wearing their faded, cherished Surrounded Islands WilliWear shirts. Now Willi Smith’s panel on the AIDS Memorial Quilt occupies block number thirteen, along with memorials for David Bailey, John T. Cyrus, Dennis Dew, Jerry Matus, Dennis R. Radabaugh, Baird Underhill, and Andreas. Comprising some 49,000 panels, the Quilt, whole and in parts, has been exhibited continually around the world since 1987.

The show attracted and excited local people who had never experienced contemporary, let alone conceptual, art. Many who had seen the work in situ showed up at the museum wearing their faded, cherished Surrounded Islands WilliWear shirts. Now Willi Smith’s panel on the AIDS Memorial Quilt occupies block number thirteen, along with memorials for David Bailey, John T. Cyrus, Dennis Dew, Jerry Matus, Dennis R. Radabaugh, Baird Underhill, and Andreas. Comprising some 49,000 panels, the Quilt, whole and in parts, has been exhibited continually around the world since 1987.

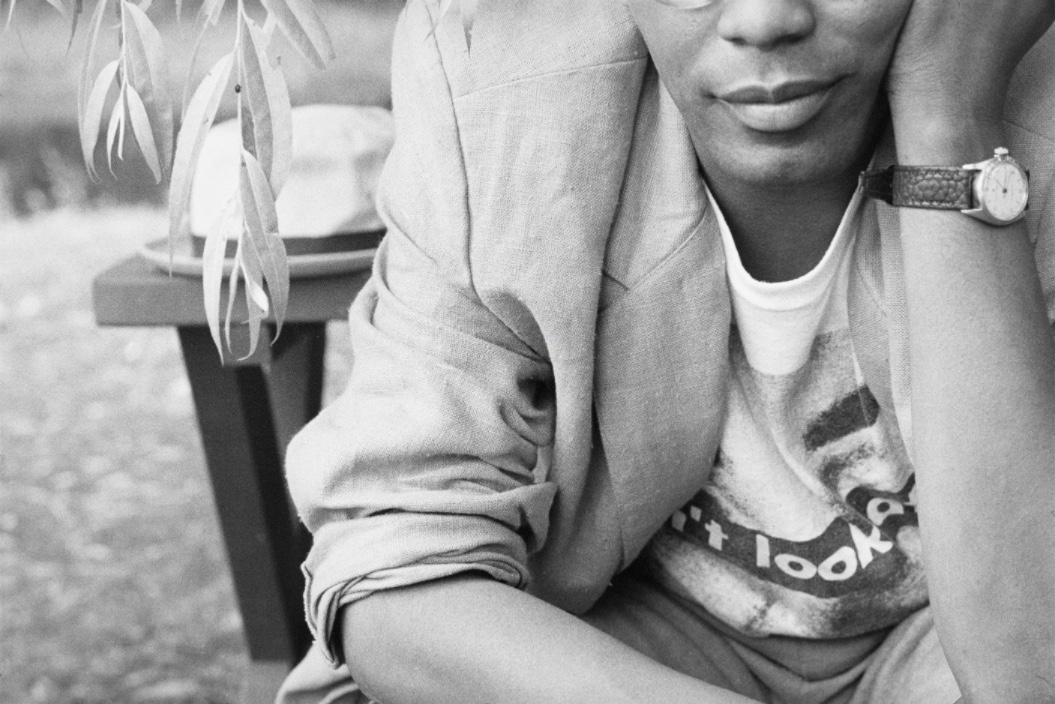

Today, Rosemary Peck’s home in Southampton is spacious and full of light, with white walls and black accents. White orchids rest on a black Joseph D’Urso table from Knoll, a twin of one she bought for Smith’s Lispenard apartment. Tucked into drawers, she also has snapshots, two drawings, an inscribed book, a slightly grayed WilliWear T-shirt with Jenny Holzer truisms, and a pair of his signature round glasses. On her wall is a photograph by Martine Barrat, an artist who’s spent decades chronicling the public and private lives of Harlem and the South Bronx. Smith was a close friend and the first collector of her work, amassing an entire wall of her photographs. It’s easy to see how closely their interests overlapped, as he once advised, “Most of these designers who have to run to Paris for color and fabric combinations should go to church on Sunday in Harlem. It’s all right there.”14 The portrait shows Willi Smith in a park, leaning forward with his head resting on his left hand and the elbow on a knee, foregrounding a round watch. He wears a rumpled linen blazer with sleeves pushed up to the elbow, a WilliWear Barbara Kruger shirt peeking out. Just like the Kruger image, his face is cropped below the eyes, emphasizing the fine curves of his nose, lips, and chin, modeled in light and resembling a fragment of Egyptian sculpture. Willow branches dangle behind him. His hat sits on a bench. The lapels of his jacket crop the shirt’s slogan from “I can’t look at you” simply to “look.”

![]() Willi Smith, Photographed by Martine Barrat, 1984

Willi Smith, Photographed by Martine Barrat, 1984

Willi Smith, Photographed by Martine Barrat, 1984

Willi Smith, Photographed by Martine Barrat, 1984

Jarrett Earnest is an artist and writer living in New York City. His interviews and essays have appeared in publications on contemporary art around the world.

- Christo, interviewed by the author, May 7, 2019.

- Barbara Kruger, interviewed by the author, May 21, 2019.

- Quoted in Gay Pauley, “Designer Willi Smith Puts Modern Art on the T-Shirt,” United Press International (February 14, 1984).

- Quoted in John Gruen, Keith Haring: The Authorized Biography (New York: Fireside, 1991), 148.

- Quoted in Joan Lebow, “WilliWear Filming in Africa, Ties in with Christo in Paris,” Women’s Wear Daily (September 13, 1985): 20.

- Christo, ibid.

- Quoted in “Butterick Introducing Willi Smith, ‘Digits’ Collection,” Fabric News (September 1973).

- Ibid.

- Bethann Hardison interview with Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, April 29, 2019.

- Laurie Mallet, interviewed by the author, May 14, 2019.

- Marilyn Bethany, “Special Effects,” New York (April 14, 1986): 46–52.

- Rosemary Peck, interviewed by the author, May 31, 2019.

- Quoted in Cindy Ruskin, The Quilt: Stories from the Names Project (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988), 100.

- Quoted in “The Bright World of Willi Smith 1948–1987,” Women’s Wear Daily (April 29, 1987).